Showing posts with label pendle witches. Show all posts

Showing posts with label pendle witches. Show all posts

Saturday, 25 February 2012

British Folk Magic & Familiar Spirits

In popular imagination, the figure of a witch is accompanied by her familiar, a black cat. Is there any historical authenticity behind this cliché?

Our ancestors in the 16th and 17th centuries believed that magic was real. Not only the poor and ignorant believed in witchcraft and the spirit world—rich and educated people believed in spellcraft just as strongly. Cunning folk were men and women who used charms and herbal cures to heal, foretell the future, and find the location of stolen property. What they did was illegal—sorcery was a hanging offence—but few were arrested. The need for the services they provided was too great. Doctors were so expensive that only the very rich could afford them and the “physick” of this era involved bleeding patients with lancets and using dangerous medicines such as mercury—your local village healer with her herbal charms was far less likely to kill you.

Those who used their magic for good were called cunning folk or charmers or blessers or wisemen and wisewomen. Those who were perceived by others as using their magic to curse and harm were called witches. But here it gets complicated. A cunning woman who performs a spell to discover the location of stolen goods would say that she is working for good. However, the person who claims to have been falsely accused of harbouring those stolen goods could turn around and accuse her of sorcery and slander. Ultimately the difference between cunning folk and witches lay in the eye of the beholder.

While witch-hunters were obsessed with extracting “evidence” of a pact between the accused witch and the devil, there’s little if any substantive proof of diabolical worship in Britain in this period. It seemed the black mass was a Continental European concept first popularised in Britain by King James I’ polemic, Daemonologie, a witch-hunter’s handbook and required reading for his magistrates.

In traditional British folk magic, it was not the devil, but the familiar spirit who took centre stage. The familiar was the cunning person’s otherworldly spirit helper who could shapeshift between human and animal form. Elizabeth Southerns, aka Old Demdike, was a cunning woman of long standing repute, arrested on witchcraft charges in the 1612 Pendle witch hunt in Lancashire, England. When interrogated by her magistrate, she made no attempt to conceal her craft. In fact she described in rich detail how her familiar spirit, Tibb, first appeared to her when she was walking past a quarry at twilight. Assuming the guise of a beautiful, golden-haired young man, his coat half black, half brown, he promised to teach her all she needed to know about the ways of magic. When not in human form, he could appear to her as a brown dog or a hare. Her partnership with Tibb would span decades.

Mother Demdike was so forthcoming about her familiar because without one, she, as a cunning woman, would be a fraud. In traditional English folk magic, it seemed that no cunning man or cunning woman could work magic without the aid of their familiar spirit—they needed this otherworldly ally to make things happen.

Black cats were not the most popular guise for a familiar to take. In fact, familiars were more likely to appear as dogs. In the Salem witch trials of 1692, two canines were put to death as suspected witch familiars.

But the familiar was just as likely to assume human form, generally the opposite gender of their human partner—cunning men usually had female spirits while cunning women usually had male spirits.

Was there a connection between the familiar spirits and the Fairy Faith, the lingering belief in fey folk and elves? Popular belief in fairies in the Early Modern period is well documented. In his 1677 book, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, Lancashire author John Webster mentions a local cunning man who claimed that his familiar spirit was none other than the Queen of Elfhame herself. In 1576, Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop, executed for witchcraft and sorcery at the Edinburgh Assizes, stated that her familiar spirit had been sent to her by the Queen of Elfhame. For more background on this subject, I highly recommend Emma Wilby’s scholarly study, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits, and Keith Thomas’s social history, Religion and the Decline of Magic.

Tuesday, 15 November 2011

The Pendle Witches and Their Magic, Part Two

Blacko Tower, a Victorian folly (ca 1890) near Malkin Tower Farm, Lancashire

The crimes of which Mother Demdike and her fellow witches were accused dated back years before the 1612 trial. The trial itself might have never happened had it not been for King James I’s obsession with the occult. Until his reign, witch persecutions had been relatively rare in England compared with Scotland and Continental Europe. But James’s book Daemonologie presented the idea of a vast conspiracy of satanic witches threatening to undermine the nation. Shakespeare wrote his play Macbeth, which presents the first depiction of a witches’ coven in English drama, in James I’s honour.

To curry favour with his monarch, Lancashire magistrate Roger Nowell of Read Hall arrested and prosecuted no fewer than twelve individuals from the Pendle region and even went to the far fetched extreme of accusing them of conspiring their very own Gunpowder Plot to blow up Lancaster Castle. Two decades before the more famous Matthew Hopkins began his witch-hunting career in East Anglia, Roger Nowell had set himself up as witchfinder general of Lancashire.

What do we actually know about Mother Demdike? At the time of her trial she appears as a widow and matriarch, living in a place called Malkin Tower with her widowed daughter Elizabeth Device, and her three grandchildren, James, Alizon, and Jennet. Her clan was very poor and supported themselves by a combination of begging and by the family business of cunning craft. The trial transcripts mention that local farmer John Nutter of Bull Hole Farm near Newchurch hired Demdike to bless his sick cattle. Interestingly John Nutter chose not to testify against her family in the trial.

Demdike’s family at Malkin Tower had a powerful rival in the form of Chattox, another widow and charmer, who lived a few miles away at West Close near Fence. Chattox allegedly bewitched to death her landlord’s son, Robert Nutter of Greenhead, for attempting to rape her daughter, Anne Redfearne. For social historians it’s interesting to see how having a fearsome reputation as a cunning woman could be the only true power a poor woman could hope to wield.

Unfortunately this could also backfire as it did with Demdike’s granddaughter, Alizon Device, who exchanged angry words with a pedlar outside Colne in March, 1612. Moments later the pedlar collapsed and suddenly went stiff and lame on one half of his body and lost the power of speech. Today we would clearly recognise this as a stroke. But the pedlar and several witnesses were convinced that Alizon had lamed her victim with witchcraft. Even she seemed to believe this herself, immediately falling to her knees and begging his forgiveness. This unfortunate event triggered the arrest of Alizon and her grandmother. Alizon wasted no time in implicating Chattox, her grandmother’s rival, and Chattox’s daughter, Anne Redfearne.

The four accused witches were interrogated by Roger Nowell, and then force-marched to Lancaster Castle, walking over fells and moorland. Both Demdike and Chattox, whose real name was Anne Whittle, were frail and elderly. It was amazing they survived the journey. In Lancaster they were handed over to the sadistic Thomas Covell, the gaoler who reputedly slashed the ears off Edward Kelly, friend of John Dee, when he was arrested on the charge of forgery. The women were chained to a ring in the floor in the bottom of the Well Tower. Although torture was officially forbidden in England, gaolers were allowed to starve and beat their prisoners at will. Being chained to a ring in the floor and kept in constant darkness would certainly feel like torture for those who had to endure it.

On Good Friday following the arrests, worried family and friends met at Malkin Tower to discuss what they would do in regard to this tragic situation. Constable John Hargreaves came to write down the names of everyone present and later Roger Nowell made further arrests, accusing these people of convening at Malkin Tower on Good Friday for a witches’ sabbat, something he would have read about in Daemonologie. The arrests didn’t stop until he had the mythical thirteen to make up the alleged coven. Twelve were kept at Lancaster and one, Jennet Preston who lived over the county line in Gisburn, Yorkshire, was sent to York. Apart from Chattox and Demdike and their immediate families, none of these newly arrested people had previous reputations as cunning folk. It seemed they were just concerned friends and neighbours who were caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Kept in such horrible conditions, Demdike died in prison before she came to trial, thus cheating the hangman. The others experienced a different fate.

The first to be arrested, Alizon was the last to be tried at Lancaster in August, 1612. Her final recorded words on the day before she was hanged for witchcraft are a moving tribute to her grandmother’s power as a healer. Roger Nowell, the prosecutor, brought John Law, the pedlar she had allegedly lamed, before her. Again Alizon begged the man’s forgiveness for her perceived crime against him. John Law, in return, said that if she had the power to lame him, she must also have the power to heal him. Alizon regrettably told him that she wasn’t able to, but if her grandmother, Old Demdike had lived, she could and would have healed him.

Mother Demdike is dead but not forgotten. By the mid-17th century, Demdike’s name became a local byword for witch, according to John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson’s Lancashire Folklore. In 1627, only fifteen years after the Pendle Witch Trial, a woman named Dorothy Shaw of Skippool, Lancashire, was accused by her neighbour of being a “witch and a Demdyke.”

History is a fluid thing that continually shapes the present. Long after her demise, Mother Demdike and her fellow Pendle Witches endure, their story and spirit woven into the living landscape, its weft and warp, like the stones and the streams that cut across the moors. Enthralled by their true history, I wrote my novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill, dedicated to their memory. Other books have been written about the Pendle Witches, but mine turns the tables, telling the story from Demdike and Alizon Device’s point of view. I longed to give these women what their world denied them—their own voice. Their voices deserve to finally be heard.

Sources:

Owen Davies, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History (Hambledon Continuum)

Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (Yale)

Malcolm Gaskill, Witchfinders: A Seventeenth Century English Tragedy (John Murray)

John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson, Lancashire Folklore (Kessinger Publishing)

King James I, Daemonologie, available online

Jonathan Lumby, The Lancashire Witch-Craze (Carnegie)

Margaret Murray, The Witch Cult in Western Europe, available online

Edgar Peel and Pat Southern, The Trials of the Lancashire Witches (Nelson)

Robert Poole, ed., The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories (Manchester University Press)

Thomas Potts, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, available online

Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic (Penguin)

John Webster, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft (Ams Pr Inc)

Emma Wilby, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits (Sussex Academic Press)

Benjamin Woolley, The Queen’s Conjuror: The Life and Magic of Dr. Dee (Flamingo)

Sunday, 23 October 2011

The Pendle Witches and Their Magic, Part 1

In 1612, in one of the most meticulously documented witch trials in English history, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest in Lancashire, Northern England were executed. In court clerk Thomas Potts’s account of the proceedings, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, published in 1613, he pays particular attention to the one alleged witch who escaped justice by dying in prison before she could come to trial. She was Elizabeth Southerns, more commonly known by her nickname, Old Demdike. According to Potts, she was the ringleader, the one who initiated all the others into witchcraft. This is how Potts describes her:

She was a very old woman, about the age of Foure-score yeares, and had been a Witch for fiftie yeares. Shee dwelt in the Forrest of Pendle, a vast place, fitte for her profession: What shee committed in her time, no man knows. . . . Shee was a generall agent for the Devill in all these partes: no man escaped her, or her Furies.

Quite impressive for an eighty-year-old lady! In England, unlike Scotland and Continental Europe, the law forbade the use of torture to extract witchcraft confessions. Thus the trial transcripts supposedly reveal Elizabeth Southerns’s voluntary confession, although her words might have been manipulated or altered by the magistrate and scribe. What’s interesting, if the trial transcripts can be believed, is that she freely confessed to being a healer and magical practitioner. Local farmers called on her to cure their children and their cattle. She described in rich detail how she first met her familiar spirit, Tibb, at the stone quarry near Newchurch in Pendle. He appeared to her at daylight gate—twilight in the local dialect—in the form of beautiful young man, his coat half black and half brown, and he promised to teach her all she needed to know about magic.

Tibb was not the “devil in disguise.” The devil, as such, appeared to be a minor figure in British witchcraft. It was the familiar spirit who took centre stage: this was the cunning person’s otherworldly spirit helper who could shapeshift between human and animal form, as Emma Wilby explains in her excellent scholarly study, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits. Mother Demdike describes Tibb appearing to her at different times in human form or in animal form. He could take the shape of a hare, a black cat, or a brown dog. It appeared that in traditional English folk magic, no cunning man or cunning woman could work magic without the aid of their spirit familiar—they needed this otherworldly ally to make things happen.

Belief in magic and the spirit world was absolutely mainstream in the 16th and 17th centuries. Not only the poor and ignorant believed in spells and witchcraft—rich and educated people believed in magic just as strongly. Dr. John Dee, conjuror to Elizabeth I, was a brilliant mathematician and cartographer and also an alchemist and ceremonial magician. In Dee’s England, more people relied on cunning folk for healing than on physicians. As Owen Davies explains in his book, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History, cunning men and women used charms to heal, foretell the future, and find the location of stolen property. What they did was technically illegal—sorcery was a hanging offence—but few were arrested for it as the demand for their services was so great. Doctors were so expensive that only the very rich could afford them and the “physick” of this era involved bleeding patients with lancets and using dangerous medicines such as mercury—your local village healer with her herbs and charms was far less likely to kill you.

In this period there were magical practitioners in every community. Those who used their magic for good were called cunning folk or charmers or blessers or wisemen and wisewomen. Those who were perceived by others as using their magic to curse and harm were called witches. But here it gets complicated. A cunning woman who performs a spell to discover the location of stolen goods would say that she is working for good. However, the person who claims to have been falsely accused of harbouring those stolen goods can turn around and accuse her of sorcery and slander. This is what happened to 16th century Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop of Edinburgh, cited by Emma Wilby in Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits. Dunlop was burned as a witch in 1576 after her “white magic” offended the wrong person. Ultimately the difference between cunning folk and witches lay in the eye of the beholder. If your neighbours turned against you and decided you were a witch, you were doomed.

Although King James I, author of the witch-hunting handbook Daemonologie, believed that witches had made a pact with the devil, there’s no actual evidence to suggest that witches or cunning folk took part in any diabolical cult. Anthropologist Margaret Murray, in her book, The Witch Cult in Western Europe, published in 1921, tried to prove that alleged witches were part of a Pagan religion that somehow survived for centuries after the Christian conversion. Most modern academics have rejected Murray’s hypothesis as unlikely. Indeed, lingering belief in an organised Pagan religion is very difficult to substantiate. So what did cunning folk like Old Demdike believe in?

Some of her family’s charms and spells were recorded in the trial transcripts and they reveal absolutely no evidence of devil worship, but instead use the ecclesiastical language of the Catholic Church, the old religion driven underground by the English Reformation. Her charm to cure a bewitched person, cited by the prosecution as evidence of diabolical sorcery, is, in fact, a moving and poetic depiction of the passion of Christ, as witnessed by the Virgin Mary. The text, in places, is very similar to the White Pater Noster, an Elizabethan prayer charm which Eamon Duffy discusses in his landmark book, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580.

It appears that Mother Demdike was a practitioner of the kind of quasi-Catholic folk magic that would have been commonplace before the Reformation. The pre-Reformation Church embraced many practises that seemed magical and mystical. People used holy water and communion bread for healing. They went on pilgrimages, left offerings at holy wells, and prayed to the saints for intercession. Some practises, such as the blessing of the wells and fields, may indeed have Pagan origins. Indeed, looking at pre-Reformation folk magic, it is very hard to untangle the strands of Catholicism from the remnants of Pagan belief, which had become so tightly interwoven.

Unfortunately Mother Demdike had the misfortune to live in a place and time when Catholicism was conflated with witchcraft. Even Reginald Scot, one of the most enlightened men of his age, believed the act of transubstantiation, the point in the Catholic mass where it is believed that the host becomes the body and blood of Christ, was an act of sorcery. In a 1645 pamphlet by Edward Fleetwood entitled A Declaration of a Strange and Wonderfull Monster, describing how a royalist woman in Lancashire supposedly gave birth to a headless baby, Lancashire is described thusly: "No part of England hath so many witches, none fuller of Papists." Keith Thomas’s social history Religion and the Decline of Magic is an excellent study on how the Reformation literally took the magic out of Christianity.

However, it would be an oversimplification to state that Mother Demdike was merely a misunderstood practitioner of Catholic folk magic. Her description of her decades-long partnership with her spirit Tibb seems to draw on something outside the boundaries of Christianity.

Although it is difficult to prove that witches and cunning folk in early modern Britain worshipped Pagan deities, the so-called fairy faith, the enduring belief in fairies and elves, is well documented. In his 1677 book The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, Lancashire author John Webster mentions a local cunning man who claimed that his familiar spirit was none other than the Queen of Elfhame herself. The Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop mentioned earlier, while being tried for witchcraft and sorcery at the Edinburgh Assizes, stated that her familiar spirit was a fairy man sent to her by the Queen of Elfhame.

Sunday, 16 October 2011

All Hallows Eve in Old Lancashire

Come Halloween, the popular imagination turns to witches. Especially in Pendle Witch Country, the rugged Pennine landscape surrounding Pendle Hill, once home to twelve individuals arrested for witchcraft in 1612. The most notorious was Elizabeth Southerns, alias Old Demdike, cunning woman of long-standing repute and the heroine of my novel Daughters of the Witching Hill.

How did these historical cunning folk celebrate All Hallows Eve?

All Hallows has its roots in the ancient feast of Samhain, which marked the end of the pastoral year and was considered particularly numinous, a time when the faery folk and the spirits of the dead roved abroad. Many of these beliefs were preserved in the Christian feast of All Hallows, which had developed into a spectacular affair by the late Middle Ages, with church bells ringing all night to comfort the souls thought to be in purgatory. Did this custom have its origin in much older rites of ancestor veneration? This threshold feast opening the season of cold and darkness allowed people to confront their deepest fears—that of death and what lay beyond. And their deepest longings—reunion with their cherished departed.

After the Reformation, these old Catholic rites were outlawed, resulting in one of the longest struggles waged by Protestant reformers against any of the traditional ecclesiastical rituals. Lay people stubbornly continued to hold vigils for their dead—a rite that could be performed without a priest and in cover of darkness. Until the early 19th century in the Lancashire parish of Whalley, some families still gathered at midnight upon All Hallows Eve. One person held a large bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the others knelt in a circle and prayed for their beloved dead until the flames burned out.

Long after the Reformation, people persisted in giving round oatcakes, called Soul-Mass Cakes to soulers, the poor who went door to door singing Souling Songs as they begged for alms on the Feast of All Souls, November 2. Each cake eaten represented a soul released from purgatory, a mystical communion with the dead.

In Glossographia, published in 1674, Thomas Blount writes:

All Souls Day, November 2d: the custom of Soul Mass cakes, which are a kind of oat cakes, that some of the richer sorts in Lancashire and Herefordshire (among the Papists there) use still to give the poor upon this day; and they, in retribution of their charity, hold themselves obliged to say this old couplet:

God have your soul,

Bones and all.

Other All Hallows folk rituals invoked the power of fire to purify and ward. In the Fylde district of Lancashire, farmers circled their fields with burning straw on the point of a fork to protect the coming crop from noxious weeds.

Fire was used to protect people from perceived evil spirits active on this night. At Longridge Fell in Lancashire, very close to Pendle Hill, the custom of ‘lating’ or hindering witches endured until the early 19th century. On All Hallows Eve, people walked up hillsides between 11 pm and midnight. Each person carried a lighted candle and if the flame went out, it was taken as a sign that an attack by a witch was impending and that the appropriate charms must be employed to protect oneself.

What do these old traditions mean to us today?

All Hallows is not just a date on the calendar, but the entire tide, or season, in which we celebrate ancestral memory and commemorate our dead. This is also the season of storytelling, of re-membering the past. The veil between the seen and unseen grows thin and we may dream true.

Wishing a blessed All Hallows Tide to all!

Source: Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain

Links:

Soul Cake Recipes

Souling Songs

Excerpt from Daughters of the Witching Hill

At Hallowtide, Liza insisted on walking up Blacko Hill, as we’d always done, for our midnight vigil on the Eve of All Saints. Under cover of darkness we crept forth with me carrying the lantern to light our way and John following with a pitchfork crowned in a great bundle of straw.

Once we reached the hilltop, after a furtive look round to make sure no one else was about, John lit the straw with the lantern flame so that the straw atop the pitchfork blazed like a torch. With him to hold the fork upright and keep an eye out for intruders, Liza and I knelt to pray for our dead. In the old days, we’d held this vigil in the church, the whole parish praying together, the darkened chapel bright as day with the many candles glowing on the saints’ altars. Now we were left to do this in secret, stealing away like criminals in the night, as though it were something shameful to hail our deceased. I prayed for my mam and grand-dad, calling out to their souls till I felt them both step through the veil to bring me comfort.

In my heart of hearts, I did not believe my loved ones were in purgatory waiting, by and by, to be let into heaven. There was no air of suffering or torment about them, only the joy of reunion. My mam, young and pretty, worked in her herb garden. She hummed a lilting tune whilst her earth-stained fingers pointed out to me the plants I must use to ease Liza’s birth pangs. Grand-Dad whispered his old charms to bless me and Liza and John.

A long spell I knelt there, held in the embrace of my beloved dead, till the straw on the pitchfork burned itself out, falling in embers and ash to the ground. Our John helped my pregnant daughter to her feet, then we made our way home through the night that no longer seemed so dark.

Labels:

all hallows,

holidays,

lancashire,

pendle witches,

reformation

Saturday, 22 January 2011

New Year, New Book

DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL, my novel exploring the true story of the Pendle Witches of 1612, is now out in paperback.

The wild, brooding landscape of Pendle Hill in Lancashire, Northern England, my home for the past nine years, gave birth to my novel, DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL, which tells the true story of the Pendle Witches.

In 1612, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest were hanged for witchcraft, but the most notorious of the accused, Bess Southerns, aka Mother Demdike, cheated the hangman by dying in prison. This is how Thomas Potts, describes her in THE WONDERFULL DISCOVERIE OF WITCHES IN THE COUNTIE OF LANCASTER:

She was a very old woman, about the age of Foure-score yeares, and had been a Witch for fiftie yeares. She dwelt in the Forrest of Pendle, a vast place, fitte for her profession: What shee committed in her time, no man knowes. . . . No man escaped her or her Furies.

Other books have been written about the Pendle Witches--both nuanced and lurid. Mine is the first to tell the tale from Bess Southerns's point of view. I longed to give her what her world denied her--her own voice.

History is a fluid thing that continually shapes the present. Set in an era of religious intolerance, political strife, suspicion, and social inequality, Bess and her family's struggle feels more relevant than ever, especially as we approach the 400th anniversary of the Pendle Witch trials in 2012.

I hope you will be as moved by their story as I am.

Here is a short video docodrama I shot with Outsider TV about a year ago:

Read an excerpt.

Read what the critics are saying about the book.

Where to buy:

Amazon.com

Amazon.co.uk

Barnes & Noble

Borders

Powells

Indiebound

The book is also available in e-book in both Kindle and Nook formats.

Sunday, 31 October 2010

All Hallows Tide in Pendle

When Halloween comes around, the popular imagination turns to ghosts and hauntings. And to witches.

Especially in my neck of the woods. I live in Pendle Witch Country, the rugged Pennine landscape surrounding Pendle Hill, once home to twelve individuals arrested for witchcraft in 1612.

Unfortunately Halloween seems to drag out all kinds of ghoulish speculation about historical witches and cunning folk in a way that is not only historically inaccurate but disrespectful to the dead. The Pendle Witches were not ghouls, but real people who were held for months in a lightless dungeon in Lancaster Castle, chained to a ring in the stone floor, before being tried without a barrister, condemned on the testimony of a nine-year-old girl, and then hanged. The historical truth is far more chilling than any fabricated horror story.

So let this All Hallows Tide be not an excuse for macabre speculation but let us light a candle in the memory of those men and women from Pendle Forest who died unjustly:

Elizabeth Southerns, Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redfearn, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Jane Bulcock, John Bulcock, and Jennet Preston.

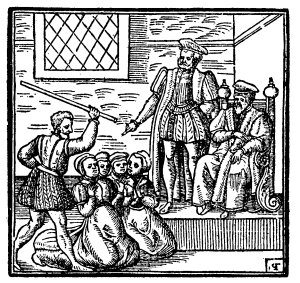

The artist Alanna Marohnic created this illustration for my article "Mother Demdike: Ancestor of My Heart" in the new "Grandmother Gaia" issue of SageWoman Magazine. However, the magazine felt the image was perhaps too disturbing. Alanna nonetheless wanted to share her artwork with me because she felt so moved by the Pendle Witches' story, she felt it in order for someone to witness what happened to them at the gallows. It is with her kind permission that I reprint the image here.

From my novel Daughters of the Witching Hill:

You’ll not find our graves anywhere. God-fearing folk do not bury witches on consecrated ground, or even in the unhallowed plot beyond the churchyard walls where the suicides and unchristened go. After I died in gaol, they burned my corpse, then buried my charred bones on the wild heath overlooking Lancaster Castle. Three months on, they did the same to Alizon, Liza, Jamie, and the rest of them hanged upon that dazzling August day. No crosses mark our resting place, just heather and nesting lapwing. Only our names lingered on and the lies they told about us.

Away in Pendle Forest, Nowell ordered his men to bring down Malkin Tower stone by stone till only the foundation remained. Yet he could never banish me and mine from these parts. This is our home. Ours. We will endure, woven into the land itself, its weft and warp, like the very stones and the streams that cut across the moors.

What is yonder that casts a light so far-shining?

My own dear children hanging from the gallows tree.

Hanging sore by twisted neck,

How they gasp and how they thrash.

Stay shut, hell door.

Let my children arise and come home to me.

Neither stick nor stake has the power to keep thee.

Open the gate wide. Step through the gate. Come, my children. Come home.

May justice be served. May ancestral memory be served. May we dream true and have a blessed All Hallows.

Especially in my neck of the woods. I live in Pendle Witch Country, the rugged Pennine landscape surrounding Pendle Hill, once home to twelve individuals arrested for witchcraft in 1612.

Unfortunately Halloween seems to drag out all kinds of ghoulish speculation about historical witches and cunning folk in a way that is not only historically inaccurate but disrespectful to the dead. The Pendle Witches were not ghouls, but real people who were held for months in a lightless dungeon in Lancaster Castle, chained to a ring in the stone floor, before being tried without a barrister, condemned on the testimony of a nine-year-old girl, and then hanged. The historical truth is far more chilling than any fabricated horror story.

So let this All Hallows Tide be not an excuse for macabre speculation but let us light a candle in the memory of those men and women from Pendle Forest who died unjustly:

Elizabeth Southerns, Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redfearn, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Jane Bulcock, John Bulcock, and Jennet Preston.

The artist Alanna Marohnic created this illustration for my article "Mother Demdike: Ancestor of My Heart" in the new "Grandmother Gaia" issue of SageWoman Magazine. However, the magazine felt the image was perhaps too disturbing. Alanna nonetheless wanted to share her artwork with me because she felt so moved by the Pendle Witches' story, she felt it in order for someone to witness what happened to them at the gallows. It is with her kind permission that I reprint the image here.

From my novel Daughters of the Witching Hill:

You’ll not find our graves anywhere. God-fearing folk do not bury witches on consecrated ground, or even in the unhallowed plot beyond the churchyard walls where the suicides and unchristened go. After I died in gaol, they burned my corpse, then buried my charred bones on the wild heath overlooking Lancaster Castle. Three months on, they did the same to Alizon, Liza, Jamie, and the rest of them hanged upon that dazzling August day. No crosses mark our resting place, just heather and nesting lapwing. Only our names lingered on and the lies they told about us.

Away in Pendle Forest, Nowell ordered his men to bring down Malkin Tower stone by stone till only the foundation remained. Yet he could never banish me and mine from these parts. This is our home. Ours. We will endure, woven into the land itself, its weft and warp, like the very stones and the streams that cut across the moors.

What is yonder that casts a light so far-shining?

My own dear children hanging from the gallows tree.

Hanging sore by twisted neck,

How they gasp and how they thrash.

Stay shut, hell door.

Let my children arise and come home to me.

Neither stick nor stake has the power to keep thee.

Open the gate wide. Step through the gate. Come, my children. Come home.

May justice be served. May ancestral memory be served. May we dream true and have a blessed All Hallows.

Labels:

all hallows,

cunning folk,

pendle witches,

witchcraft

Friday, 22 October 2010

Writing Women Back into History

This illustration, from Wikipedia Media Commons, depicts medieval women hunting.

This article of mine was originally published in the May 2008 issue of Solander Magazine, published by the Historical Novel Society.

We have been lost to each other for so long. My name means nothing to you. My memory is dust.

This is not your fault or mine. The chain connecting mother to daughter was broken and the word passed into the keeping of men, who had no way of knowing. That is why I became a footnote, my story a brief detour between the well-known history of my father and the celebrated chronicle of my brother.

Anita Diamant, The Red Tent

To a large extent, women have been written out of history. Their lives and deeds have become lost to us. To uncover the buried histories of women, we historical novelists must act as detectives, studying the sparse clues that have been handed down to us. To create engaging and nuanced portraits of women in history, we must learn to read between the lines and fill in the blanks.

At its best, historical fiction can indeed play a crucial role in writing women back into history and challenging our misperceptions about women in the past. In her stunning novel The Red Tent, Anita Diamant turns our image of women in the Old Testament on its head by allowing the Biblical Dinah to tell her own story in her own voice. Donna Cross’s novel Pope Joan explores the tantalizing possibility that a 9th century woman might have once sat on the papal throne. In The Thrall’s Tale, Judith Lindbergh paints an unforgettable portrait of Thorbjorg, the 10th century Norse seidkona, or seeress, straight off the pages of the Saga of Erik the Red. Paul Anderson’s 1376 page epic Hunger’s Brides illuminates the life of Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, a 17th century Mexican nun who became the greatest New World poet of her age. Sor Juana fans will also want to read Alicia Gaspar de Alba’s novel Sor Juana’s Second Dream.

While many authors have focused on documented historical figures, others have embraced the ellipses in history as an invitation to speculate on women’s secret lives and untold stories. “Where history and biography are about the public world, fiction is about the private world,” says Jude Morgan, author of Passion and Indiscretion. “And that [private world] was perforce the women’s world, too: the private, often including the hidden and the unspoken. That’s where historical fiction can be revealing.” In her novels Tipping the Velvet, Affinity and Fingersmith, Sarah Waters imagines the smoldering passions that might have passed between women behind the façade of prim Victorian decorum. Jean Rhys, in her masterpiece Wide Sargasso Sea, resurrects the silenced Mrs. Rochester, the madwoman in the attic in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, and brings her to life as a tragically misunderstood Creole heiress. Louise Erdrich has written an entire body of work portraying the women (and men) of her mother’s line, the Anishinaabe Nation.

Not surprisingly, many of these novels that capture the hidden truths of women’s histories have been runaway bestsellers. Diamant’s Red Tent, first published in 1997 with no advertising budget, became a word of mouth blockbuster and went on to sell to 25 foreign markets, while Cross’s Pope Joan is now in its 18th printing and inspired a major motion picture starring German-born actress Franka Potente. Louise Erdrich’s National Book Critics Circle Award-winning first novel Love Medicine has never been out of print.

At the end of the day, it’s a question of knowing your market. Although it’s hard to pin-point precise figures, the majority of buyers and readers of historical fiction appear to be women and they seem to crave books that present compelling portraits of strong female protagonists.

Most interesting is the possibility that historical fiction’s rewriting of women’s history has wider repercussions in the world of nonfiction.

“Historical fiction has a way of bringing figures neglected (or subordinated) by the history books back into the foreground,” says Bethany Latham, Managing Editor of HNR. “Historical fiction can do this where history tomes fail because it is fiction –it’s not bound strictly by documented fact. For instance, an historical fiction author can write an engrossing novel centering around a ‘minor’ female courtier, where a truly enlightening biography of the woman is problematic due to the dearth of historical information about her (think Philippa Gregory's Boleyn Inheritance versus Julia Fox’s exceedingly speculative biography of Viscountess Rochford).

“Historical fiction treatments thrust historical female figures, whether they be aristocrats or serving maids, into the public eye,” Latham continues. “Nonfiction authors cannot help but be influenced by the rampant popularity of a particular historical period or person promulgated by historical fiction and the screen adaptations the novels spawn; it causes them to look for their own ‘angle’ – for what hasn’t been done, what’s been overlooked – in order to focus their research on it. . . . Historical fiction can grab [women] by the farthingale and drag them into the limelight, leading to greater interest in them, more research into their lives, and subsequently a greater understanding of the part women have played in history.”

jay Dixon, author of The Romance Fiction of Mills & Boon: 1909-1990s, speculates that historical novelists may have been pioneers in the women’s history movement. “Ever since the publication of Sheila Rowbotham’s Hidden from History in 1973, feminists have been trying to rescue women from their invisibility in male discourses of history,” says Dixon. “But prior to that, women authors, in their historical novels, fore-fronted women – the wealthy, the poor, the powerful and the downtrodden – from all periods and all locales. Using imagination alongside research, they told the stories that could have happened, and maybe did. And in doing so not only gave voices to the voiceless, but also changed our perception of the past.”

HNR Editor Sarah Johnson cites Anya Seton’s classic novel The Winthrop Woman, first published in 1958, which tells the story of 17th century Elizabeth Winthrop, wife of Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The novel reveals how she defied her husband and community in order to befriend Anne Hutchinson, the famous heretic who later went on to found the colony of Rhode Island.

Exploding myths

Unfortunately writers can run into problems when they present a view of historical women that challenges our common misperceptions. On the one hand, readers and critics are justifiably skeptical about novelists who present plucky historical heroines with attitudes that feel too contemporary and thus anachronistic to their time and place. On the other hand, if you sit down and do the research, you will discover that every epoch had its radical voices, movers and shakers, extraordinary women who rocked the establishment. Think of Sappho, Hypatia, Hildegard of Bingen, Elizabeth I of England, Aphra Benn, Anne Bonny the Pirate Queen, Emma Goldman, and Rosa Parks, to name a few. Too often readers and, unfortunately some reviewers, appear to have a distorted and uninformed view of women in history and seem too quick to label any strong heroine anachronistic, even if the author has backed up the fiction with considerable research. Too often we base our picture of women in the past on the lazy assumption that all women throughout all of history were completely downtrodden and disempowered.

In preparation for the Rewriting Women’s History panel at the 2007 HNS North American Conference in Albany, New York, I conducted an informal survey with members of the HNS email discussion list, asking what they thought were the most annoying historical clichés about women. Here are some of the responses:

Women’s lives were completely limited to the domestic sphere.

Before Betty Friedan came along, all women were housewives and mothers and nothing else.

Women in the Victorian era led lives of leisure. (In fact, very few did.)

Women in the past did not enjoy sex.

Dr. Irene Burgess, Provost and Dean of Eureka College, Illinois, reminds us that what we know – or think we know – about women in history is mediated and changes over time. “Representing historical women in twenty-first century fiction can be difficult,” Burgess points out, “because of the automatic lenses that a current audience places on the behavior of women from an older period. Because mores and language were so different, it’s frequently difficult for current-day readers to believe that women of the past had autonomy, capability, and choice.

“A lower class woman of the 14th century in England,” Burgess continues, “probably had greater degrees of freedom than an aristocratic woman of the 18th century in Italy. Although readers may perceive it as anachronistic to have a female weaver going to the tavern with some of her friends and telling her husband to take a hike if he protests, that probably did happen.”

Dr. Samantha Riches, Director of Studies for History and Archaeology at Lancaster University, UK, agrees that the reality of medieval women’s lives defy our popular conceptions. “The idea that women sat around creating tapestries and looking wistful is still quite widespread, largely due to Hollywood films perpetuating the same stereotyped ideas. Sources about women’s personal experiences are few and far between, but we do have a few gems like the Paston letters (accessible via the Internet Medieval Sourcebook), which can give us a real insight into the lives of late medieval women. In 1448 Margaret Paston wrote to her husband John with a shopping list including almonds, sugar and crossbows: he was away in London and she was aware that she would need to organize defense of their property in East Anglia against a neighbor with whom they were involved in a dispute.”

Although there are even fewer sources regarding the lives of common women, Riches believes that the visual evidence tends to indicate that women were employed in a wide range of occupations. Erika Uitz’s scholarly study Women in the Medieval Town reveals that women worked as merchants, money-lenders, brewers, and even miners. One of the book’s illustrations shows a detail of Hans Hesse’s early 16th century “Miners’ Altar” panel painting, which depicts a woman washing the heavy iron ore—a job that was even more backbreaking than mining.

The colorful lives of medieval women have inspired Paul Doherty’s most recent mystery series, centered on 14th century physician Mathilde of Westminster, who is based on a historical figure. “We tend to think of women’s rights developing over the centuries; this is simply not true,” Doherty said when I interviewed him in the May 2006 Historical Novels Review. “I think it was Dorothy Mary Stenton, the famous Anglo-Saxon historian, who pointed out that women had more rights in 1100 then they did in 1800!”

Indeed, the 1800s would appear a big stumbling block in our perceptions of the past. “The early 19th century marked the nadir of European women’s options and possibilities,” Bonnie S. Anderson and Judith P. Zinsser write in A History of Their Own, Volume 2. “The creation of ‘women’s movements’ in the 19th century was in part a response to this.”

The Victorian era in particular has made a lasting imprint on the modern psyche. Suzanne Adair, author of Paper Woman and panelist at the Albany conference, notes that too often people look at women in the past through the lens of Victorian culture and base their view of women in completely disparate epochs on this stilted stereotype of the tightly corseted, sexually repressed Angel of the Home. “We like to think of ourselves as much more progressive than earlier generations,” Irene Burgess adds, “but when it comes to issues such as sexuality and the body, we actually are more repressed – a product of our Victorian ancestry. One only has to think of the Wife of Bath or the poems of Sappho to realize that that is the case.”

But even 19th century women’s lives were more complex than many realize: the Industrial Revolution drove countless women and girls out of the kitchens and into factories and mills, inspiring the line in the popular early 19th century folksong, The Weaver and the Factory Maid:

Where are the girls? I will tell you plain:

The girls have gone to weave by steam,

And to find them you must rise at dawn,

And trudge to the mill in the early morn.

As astute historians will point out, women throughout history have always worked. One of the experiences that inspired my third novel, The Vanishing Point, set in Colonial America, was a visit to a tiny Philadelphia row house where two 18th century seamstresses once lived and plied their trade. I felt immediately drawn into their world. It was exciting for me to see the proof that even in this era, when nearly every factor of the dominant religion and economy herded women into marriage and domesticity, some women still succeeded in carving out independent, masterless lives, ruled by neither father nor husband.

In Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650-1750, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich reveals that wives in Colonial America frequently acted as their spouse’s business partners, running shops and farms in tandem with their men, and sometimes taking over the role of “deputy husband,” which meant shouldering male duties, sometimes acting as surrogate if the husband were away. She cites one Edith Creford of Salem, Massachusetts, who acted as an attorney for her husband and signed a promissory note for £33, a considerable sum at that time. While researching my article Portals to Hidden Histories (Solander, November 2006), which showcased the living history sites at Historic St. Mary’s City, Jamestown Settlement and Colonial Williamsburg, I learned of 18th century businesswomen and entrepreneurs, such as Jane Vobe, who ran the King’s Arms Tavern in Williamsburg and Ann Wager, who founded the Bray School for African American children in 1760.

But the details of how women contributed to the economy tend to get buried under the perceived restrictions on these women’s lives and their subordinate place in their culture. When examining the rules women are expected to follow, Irene Burgess reminds us that “that rules and injunctions are only put in place when people actually do the behavior that is being controlled. So, ‘thou shalt not kill’ wouldn’t have been necessary if human beings weren’t so fond of slaughter. Similarly, telling women they had to be ‘chaste, silent, and obedient’ meant that probably, for the most part, women were not any of those things.”

Practical Writing Advice

So how can historical novelists create strong, authentic, and convincing female characters without resorting to either anachronism or lazy stereotypes?

Pick Your Heroine

Perhaps the most straightforward method is to choose an arresting historical figure, either famous or obscure, and delve deep into the research in order to bring her to life. Ask yourself what historical personae appeal to you and why.

“When I chose Juana la Loca as the subject for my second novel, I knew I’d set myself up for a challenge.” says CW Gortner, whose novel The Last Queen is published by Ballantine. “I’ve been obsessed by her since my childhood in Spain and I found the lurid myth of her life hard to believe. History is rarely kind to women, particularly women in power, so I set out to discover if the story of the ‘mad queen of Spain’ was true. It took six years of delving, but slowly the web of misinformation and calumny began to unravel. For nearly five hundred years, Juana of Castile’s story has been distorted because she posed a threat.”

Internationally best-selling author Sandra Gulland followed up her wildly popular Josephine Bonaparte Trilogy with a new novel focused on a much more elusive character: Louise de la Vallière, the first mistress of the Sun King, Louis XIV. “She is described as timid, something of a wallflower,” says Gulland of her heroine. “She was a daring horsewoman, a mistress to the Sun King, a Carmelite nun. The combination of these qualities intrigued me.”

Michelle Moran, whose debut novel Nefertiti was a national bestseller, finds herself drawn to the stories of infamous women whose lives have previously only been narrated through the words of men. “I’ve never been able to believe that women throughout history fit neatly into the simple categories that ancient writers created for them: that of the loyal virgin or the scheming harlot,” Moran states. “From Jezebel to Nefertiti, I find that rewriting women’s history is not just a career, it’s a calling.”

Zoom in on a specific historical event

The Pendle Witch Trial of 1612 provided the foundation for my most recent novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Seven women and two men were hanged as witches, based on the “evidence” given by a nine-year-old girl, who betrayed and condemned her own family. The most notorious of all the witches was the girl’s grandmother, Elizabeth Southerns, aka Old Demdike, who died in Lancaster Gaol before she came to trial. Researching the trial, I was deeply drawn into this family tragedy, especially the tale of Southerns herself, a cunning woman and healer of long standing, whose “charms” were Catholic prayers and whose reputation was so fearsome that court clerk Thomas Potts wrote that “no man escaped her, or her Furies.”

Katharine Weber’s acclaimed novel Triangle centers on the Triangle shirtwaist factory fire of 1911. “It was striking to me how little the fire had been written about in books from then until the mid 1960s when a flourishing industry of books about the Triangle fire, most of them written for young girls, suddenly appeared, and have continued to appear every year. Why? It has to be the women’s movement. This helped me focus on one of the crucial themes of my novel, the way we don’t just tell our stories with agendas, we listen with agendas as well. . . . Triangle, like the fire itself, is a story about courageous women whose bravery was mostly obscured by the agendas of the moment.”

Focus on a particular subculture

One way to come up with a unique angle on history is to select your favorite historical period and then delve into a corner of that society that fascinates you.

Susanne Dunlap’s novels Emilie’s Voice and Liszt’s Kiss revolve around the world of music in 18th and 19th century Europe. Dunlap, who has a doctorate in music history from Yale, says that music was one way that talented women could distinguish themselves. “Women as performers were placed in the public eye and often then considered damaged goods – like prostitutes,” says Dunlap. “But many were able to support themselves and lead fulfilling artistic lives as singers, pianists, actresses. They achieved independence, and that was considered dangerous by men. Women as true creative artists – composers, painters, authors – were even more dangerous. Those are the stories that intrigue me, and give me the opportunity to rewrite women’s history.”

Keep it real for the reader

Author Melinda Hammond (A Rational Romance), who also writes as Sarah Mallory, reminds us that it’s essential to get the details right to keep your fiction convincing. “The trick is to create characters that are true to the period, yet have a resonance for a modern reader,” says Hammond. “It is important that we make readers aware of the prevailing customs and culture of a particular period or they will not understand why our characters act in a particular way. It is up to the writer to ‘set the stage,’ capture the spirit of the period and create the right background for the characters.”

Hammond believes that this is especially pertinent for romantic fiction. “In historical terms, romance is a relatively modern concept,” she explains. “It’s only in the last couple of centuries that people have come to expect to fall in love and marry.”

The future of women’s history

Samantha Riches believes that academic historians are moving away from the concept of “woman as other” to a more complex, multilayered view of the past. “For the last twenty to thirty years women’s history has been ‘recovered’ by academic historians, led by feminist commentators, not to the fullest extent possible for sure, but nevertheless I would argue that women are now featuring strongly in many studies of the past,” Riches states. “The extent to which this change has filtered through into popular perceptions is another matter, but I’d like to think that there is a gradual shift towards seeing the history of women as something that is integral to the study and understanding of the past, rather than as something separate and different.”

Sandra Gulland describes history as a continually moving target. “Our story of the past, how we understand it, is constantly in flux. New discoveries, new perspectives: all these help us to revise – reVISION – the past, or rather: the story of our past.”

Wednesday, 2 June 2010

Interview with Katherine Howe!

This interview is published on Amazon.com.

Katherine Howe is the bestselling author of The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane and a descendant of both Elizabeth Proctor, who survived the Salem witch trials, and Elizabeth Howe, who did not. Read her interview with Mary Sharratt, author of Daughters of the Witching Hill:

Katherine Howe: I am so looking forward to learning more about Daughters of the Witching Hill. As I started the book, I was curious about something. The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane covers some well-worn territory in American history: the Salem witch trials, which we all learn about in school so early that it's hard to really know when they appear for the first time in our culture. Can the same be said for the Pendle witches in British history? If so, how did you feel about revisiting something already so well known? And if not, how did you first learn about them?

Mary Sharratt: It's so wonderful to be doing this interview with you. I'm such a fan of The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane!

Unlike the Salem Trials which are so well known that they've become almost a part of the American psyche, I wouldn't say that the Pendle Witches are that well known outside the Pendle region. I think many people in other parts of England might find them as unfamiliar as Americans would. The most famous English witch trials would be those associated with Matthew Hopkins’s career as a witchfinder during the anarchy that ensued during the English Civil War.

So, although the Pendle Witch Trials were meticulously documented by court clerk Thomas Potts in his book, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, I'd say that they are not so well known. Novels and academic studies have been written about them, of course, but not so many that I felt like I was treading on over-familiar ground.

KH: I am not surprised to hear that the Pendle witches are a bit more obscure than Matthew Hopkins' witches. How did you first stumble upon this mysterious history in your area?

MS: When I first moved to the Pendle region in 2002, I hadn't heard anything about the Pendle Witches, but once you are in the region, it's impossible to ignore this history. There are images of witches everywhere: on private houses, pubs, bumper stickers, walking trail signs, realtors' logos, a whole fleet of commuter buses going into Manchester.

At first I thought these witches belonged to the realm of fairy tale and folklore, but once I learned the actual history, I was so moved by their story. Seven women and two men from this region were hanged for witchcraft at Lancaster in 1612, but the most notorious among them, Elizabeth Southerns, aka Old Demdike, the heroine of my book, died in prison before she came to trial. She was a cunning woman and healer of long-standing repute who had practiced her craft for decades before anyone dared to interfere with her or stand in her way. Another accused witch, Mother Chattox, was also a renowned cunning woman--Mother Demdike's rival. Alizon Device, Demdike's granddaughter, was first to be arrested and last to be tried at Lancaster. Her last recorded words before she was hanged were a passionate vindication of her grandmother's legacy as a healer.

What moved me was not only the family loyalty but the fact that these women believed in their own powers and made no attempt to hide who they were when interrogated by their magistrate. They seemed very proud of their perceived powers.

KH: I was particularly intrigued by your representation of the relationship between the cunning folk tradition in late Medieval and early modern England with the loss of the Catholic faith and its mysteries. In effect it seems as though Demdike and her family are merely adherents of what the book calls the "old religion," though the story is often agnostic on whether that term refers to Catholicism or to something pre-Christian. I gather that some of that representation draws on the work of Keith Thomas, a historian whose work I relied on for research as well, though I was trying to uncover ways in which the cunning folk tradition might have persisted even for adherents of Puritanism. Can you tell me about some of the other research that you did to really root the story in historical truth?

MS: I based all the major events and details on the primary source material, Thomas Potts's The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster. Here you can see the accused witches' charms quoted by the prosecution and cited as damning evidence of satanic witchcraft. However, the charms contain not a shred of diabolical imagery. They are Catholic prayer charms. The charm to heal a person who is bewitched, attributed to Mother Demdike's family, is a moving description of the passion of Christ as witnessed by the charm contains language very similar to the White Pater Noster, an Elizabethan prayer charm discussed in Eamon Duffy's landmark work, Stripping the Altars: Traditional Religion in England: 1400-1580. So the Catholic connection is based on fact and this was one of the things that surprised me most in my research, because I hadn't even considered such a connection.

Keith Thomas's Religion and the Decline of Magic was hugely influential to my writing, but my research also draws on a course I did at Lancaster University on Late Medieval Belief and Superstition. There was much mysticism and mystery associated the pre-Reformation Catholicism and indeed the yearly round of village holidays took place under the blessing of the old Church, even festivals we associate as pagan, such as May Day, were adopted or appropriated, depending on one's viewpoint. So, pre-Reformation, one could be a mainstream Christian and still embrace a worldview that made room for positive folk magic. It was believed that certain prayers could aid healing. Mother Chattox's charm to heal a bewitched person, for example, involves saying five Pater Nosters, five Ave Marias, and the Creed, while picturing the five wounds of Christ. You could pray to a certain saint or visit a holy well, and so on. Puritanism stripped all these blessings away, yet people still faced the same harsh fears of the evil supernatural, but no longer had the "good" charms to protect them. So it's no wonder that older people like Mother Demdike, who would have remembered the old Church, clung on to these prayers and healing charms.

On the other hand, the belief in familiar spirits, which was the foundation of English folk magic, seemed to draw on a faith quite different from Christianity. It's difficult to substantiate that historical witches and cunning folk believed in anything like modern Wicca, but the lingering belief in fairies and elves in this period is well established, and I followed the theory advanced by people like Emma Wilby, author of the scholarly study Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits, that the belief in familiar spirits was intimately connected with this lingering fairy faith, something that co-existed for centuries with Christianity. In his 1677 book, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, Lancashire author John Webster talks about a local cunning man who claimed that his familiar spirit was none other than the Queen of Elfhame herself.

KH: Just a quick last question: One of the most common questions that readers ask me is whether or not writing about witches has made me more superstitious. So now I would like to ask you the same thing: has writing about witches made you see the world differently? And do you think lungwort will grow well in a New England garden, as you have now inspired me to try?

MS: Katherine, writing this book was such a magical experience for me. I identified with my heroines, Mother Demdike and Alizon, to the point where I "heard" their voices as I was writing their story--or letting them tell their own stories through me. I felt a powerful connection with the land and with these women whose spirit lives on in the land. I can't just walk down a country lane or footpath again without feeling that connection to every herb and tree and animal that crosses my path. And I find myself counting magpies.

You could always try planting lungwort and let me know how it grows!

(Photo © Laura Dandaneau)

Tuesday, 30 March 2010

Pendle Witch Library

Pendle Witches: Further Reading on the Pendle Witches, Historical Cunning Folk, and Wisewomen

Fiction:

Harrison Ainsworth, The Lancashire Witches: A Romance of Pendle Forest (EJ Morten) (First published in 1849, written in dialect, very long, gothic, and dense.)

Robert Neill, Mist Over Pendle (A lovely novel for both adults and young adults but not very kind to the witches!)

Nonfiction, Primary Source:

Thomas Potts, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster (Published in 1613, these are the official transcripts of the 1612 trial. Though not infallible, Potts’s account remains the best primary source we have.)

Nonfiction, Secondary Sources:

John A. Clayton, The Lancashire Witch Conspiracy (Barrowford) (A locally published historical investigation.)

Jonathan Lumby, The Lancashire Witch-Craze (Carnegie) (Very in-depth and sensitively written.)

Edgar Peel & Pat Southern, The Trials of the Lancashire Witches (Nelson) (Perhaps the most lucid overview of the arrests and trials.)

Robert Poole, ed., The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories (Manchester University Press) (A collection of recent academic scholarship on the subject, highly recommended!)

Nonfiction: Books on Witchcraft, Folk Magic, Folk Lore, Religion, and Social History

Robin Briggs, Witches & Neighbours: The Social and Cultural Context of European Witchcraft, (Blackwell Publishing) (General overview of the European witch persecutions.)

Owen Davies, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History, (Hambledon Continuum) (Although most of the cunning-folk he discusses date from a later period than the Pendle Witches, this is still a must-read.)

Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (Yale University Press) (Seminal work on why people in Tudor England were so reluctant to lose their “old religion.”)

John Harland & T.T. Wilkinson, Lancashire Folklore, (Kessinger Publishing) (Originally compiled in the 19th century, this book is full of authentic folk magic as practised by local cunning folk.)

Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, (Penguin) (The classic social history on religion and popular folk magic and how they influenced each other.)

John Webster, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, (Ams Pr Inc), (Originally published in 1677, this is a skeptical work dismissing accusations of supposed satanic witchcraft and yet illuminating genuine folkloric beliefs and practises, including the lingering belief in the Fairy Faith.)

Emma Wilby, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic, (Sussex Academic Press) (Scholarly work attempting to elucidate what cunning folk actually believed in. The author presents a convincing argument that the belief in familiar spirits was rooted in the Fairy Faith.)

Fiction:

Harrison Ainsworth, The Lancashire Witches: A Romance of Pendle Forest (EJ Morten) (First published in 1849, written in dialect, very long, gothic, and dense.)

Robert Neill, Mist Over Pendle (A lovely novel for both adults and young adults but not very kind to the witches!)

Nonfiction, Primary Source:

Thomas Potts, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster (Published in 1613, these are the official transcripts of the 1612 trial. Though not infallible, Potts’s account remains the best primary source we have.)

Nonfiction, Secondary Sources:

John A. Clayton, The Lancashire Witch Conspiracy (Barrowford) (A locally published historical investigation.)

Jonathan Lumby, The Lancashire Witch-Craze (Carnegie) (Very in-depth and sensitively written.)

Edgar Peel & Pat Southern, The Trials of the Lancashire Witches (Nelson) (Perhaps the most lucid overview of the arrests and trials.)

Robert Poole, ed., The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories (Manchester University Press) (A collection of recent academic scholarship on the subject, highly recommended!)

Nonfiction: Books on Witchcraft, Folk Magic, Folk Lore, Religion, and Social History

Robin Briggs, Witches & Neighbours: The Social and Cultural Context of European Witchcraft, (Blackwell Publishing) (General overview of the European witch persecutions.)

Owen Davies, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History, (Hambledon Continuum) (Although most of the cunning-folk he discusses date from a later period than the Pendle Witches, this is still a must-read.)

Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (Yale University Press) (Seminal work on why people in Tudor England were so reluctant to lose their “old religion.”)

John Harland & T.T. Wilkinson, Lancashire Folklore, (Kessinger Publishing) (Originally compiled in the 19th century, this book is full of authentic folk magic as practised by local cunning folk.)

Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, (Penguin) (The classic social history on religion and popular folk magic and how they influenced each other.)

John Webster, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, (Ams Pr Inc), (Originally published in 1677, this is a skeptical work dismissing accusations of supposed satanic witchcraft and yet illuminating genuine folkloric beliefs and practises, including the lingering belief in the Fairy Faith.)

Emma Wilby, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic, (Sussex Academic Press) (Scholarly work attempting to elucidate what cunning folk actually believed in. The author presents a convincing argument that the belief in familiar spirits was rooted in the Fairy Faith.)

The Charms of the Pendle Witches

From Thomas Potts’s A Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, the official trial transcripts:

Mother Demdike’s family charm “to get drink”:

Crucifixus hoc signum vitam

Eternam. Amen.

(Literal translation: the crucifix is the sign of eternal life.)

This charm to cure bewitchment is attributed to Chattox:

A Charme

Three Biters hast thou bitten,

The Hart, ill Eye, ill Tonge:

Three bitter shall be thy Boote,

Father, Sonne, and Holy Ghost

a Gods name,

Fiue Pater-nosters, fiue Auies,

and a Creede,

In worship of fiue wounds

of our Lord.

(In modern language the last part would read: five Pater-Nosters, five Ave Marias, and a Creed, in the worship of the five wounds of our Lord—the cunning woman would then say these prayers while contemplating the five wounds of Christ.)

A charm to cure one who is bewitched, attributed to Elizabeth Southerns’s family and recorded by Thomas Potts during the 1612 witch trials at Lancaster:

A Charme

Upon Good-Friday, I will fast while I may

Untill I heare them knell

Our Lords owne Bell,

Lord in his messe

With his twelve Apostles good,

What hath he in his hand

Ligh in leath wand:

What hath he in his other hand?

Heavens doore key,

Open, open Heaven doore keyes,

Steck, steck hell doore.

Let Crizum child

Goe to it Mother mild,

What is yonder that casts a light so farrandly,

Mine owne deare Sonne that’s naild to the Tree.

He is naild sore by the heart and hand,

And holy harne Panne,

Well is that man

That Fryday spell can

His Childe to learne;

A Cross of Blew, and another of Red,

As good Lord was to the Roode.

Gabriel laid him downe to sleepe

Upon the ground of holy weepe:

Good Lord came walking by,

Sleep’st thou, wak’st thou Gabriel,

No Lord I am sted with sticke and stake,

That I can neither sleepe nor wake:

Rise up Gabriel and goe with me,

The stick nor the stake shall never deere thee.

Daughters of the Witching Hill: What the critics are saying

Daughters of the Witching Hill by Mary Sharratt

published April 7, 2010 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

“Gorgeously imagined . . . . Sharratt crafts her complex yet credible account by seamlessly blending historical fact, modern psychology, and vivid evocations of the daily life of the poor whose only hope of empowerment lay in the black arts.”

-Publisher’s Weekly, Starred Review

“What makes this story stand out are the strong voices of the two main characters, stalwart Bess Southerns (aka Demdike) and her feisty granddaughter Alizon Device . . . . a fascinating tale. The story unfolds without melodrama and is therefore all the more powerful.”

-Library Journal, Starred Review

“The Pendle witches’ story, retold as a passionate saga of female friendship.”

-Kirkus Reviews

“Sharratt fills the book with fascinating accounts of rituals and magic practices, and her gift for the language of the era brings the narrative to life. Striking just the right balance between the demands of fact and the allure of a good story, she has produced a novel that’s both convincing and compelling. Daughters is—literally—a spellbinding book.”

-Bookpage

"Sharratt gives the story a sense of magical wonder as she weaves 17th century folklore into the hard lives of her characters."

-Mary Ann Grossmann, Saint Paul Pioneer Press

published April 7, 2010 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

“Gorgeously imagined . . . . Sharratt crafts her complex yet credible account by seamlessly blending historical fact, modern psychology, and vivid evocations of the daily life of the poor whose only hope of empowerment lay in the black arts.”

-Publisher’s Weekly, Starred Review

“What makes this story stand out are the strong voices of the two main characters, stalwart Bess Southerns (aka Demdike) and her feisty granddaughter Alizon Device . . . . a fascinating tale. The story unfolds without melodrama and is therefore all the more powerful.”

-Library Journal, Starred Review

“The Pendle witches’ story, retold as a passionate saga of female friendship.”

-Kirkus Reviews

“Sharratt fills the book with fascinating accounts of rituals and magic practices, and her gift for the language of the era brings the narrative to life. Striking just the right balance between the demands of fact and the allure of a good story, she has produced a novel that’s both convincing and compelling. Daughters is—literally—a spellbinding book.”

-Bookpage

"Sharratt gives the story a sense of magical wonder as she weaves 17th century folklore into the hard lives of her characters."

-Mary Ann Grossmann, Saint Paul Pioneer Press

Daughters of the Witching Hill: The Launch Party

Daughters of the Witching Hill

published April 7 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

What a voice Mary Sharratt has. She brings a haunting, ancient story to life.

--Karleen Koen

The wild, brooding landscape of Pendle Hill in Lancashire, Northern England, my home for the past seven years, gave birth to my new novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill, which reveals the true and unforgettable story of the Pendle Witches of 1612.

Take a sneak peak of the novel

Who were the Pendle Witches of 1612?

Read what the critics are saying

Join me on my traditional and virtual book tour

Watch my docudrama of the Pendle Witches, filmed live on location around Pendle Hill

Read Mary Ann Grossmann's interview with me in the Saint Paul Pioneer Press

Learn the charms of the Pendle Witches

Enter the Daughters of the Witching Hill Reader Review Contest

Learn more about Historical Cunning Folk and Wisewomen

Thank you for being a part of this book!

Tuesday, 23 March 2010

New video, live events, audio rights, and new reviews

I've just returned from New York and the stellar Virginia Book Fesitval.

In Brooklyn, artist and author Kris Waldherr hosted my exclusive prepublication reading and signing at her Art & Words Gallery, pictured above. You can see some of her gorgeous art work on the wall behind me. You can also see how beautiful the finished book jacket for DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL is. It shimmers like a hologram and completely conveys the essence of the magic I sought to capture in the novel.

The event was livestreamed on the internet and you can see it here.

At the Virginia Festival of the Book I had the honour of being on three panels.

First, I was a guest speaker for Bella Stander's Book Promotion 101 seminar at Writer House in Charlottesville.

Then I was lucky enough to take part in the divine Barbara Drummond Mead's Reading Group Choices Panel with authors Masha Hamilton, Sheila Curran, and Laura Brodie.

I have to read all their books now.

Ditto with the authors of the third panel, Larry Baker's True Stories of Fact or Fiction panel with Roger Ekirch, Ben Farmer, and C.M. Mayo. Ben Farmer is only 28 and this was his first public book event. His debut novel EVANGELINE looks so compelling. I had a wonderful chat with C.M. Mayo who lives in Mexico and writes great fiction about Mexico's turbulent history.

In early April I leave for book tour with dates in Boston, Salem, and Minnesota where I hope to meet with my lovely readers!

Here is the video docudrama we shot for DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL, on location around Pendle Hill. My publisher has now added the book jacket and pub date to the video. In this short film, I discuss my research on the Pendle Witches as historical cunning folk.

In addition, DAUGHTERS has received a rave review from Bookpage. As I post this, their site seems to be down but the link should work when their site is back up.

And insightful reviews from Goddess Pages and Pagan Book Reviews.

My other great news is that Houghton Mifflin Harcourt sold the audio rights to both DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL and THE VANISHING POINT, and that my publicist told me that the rave March 1 review from Library Journal was actually a Starred Review. So that means that DAUGHTERS received two Starred Reviews, one from Publisher's Weekly and one from Library Journal.

My heroines, the Pendle Witches, were real people so I sincerely hope that this book can serve their memory and do justice to their legacy. Their story deserves to be heard.

Wednesday, 10 March 2010

King James I: Royal Demonologist

Even by the standards of his age, King James VI of Scotland, who later became James I of England, stood out as a deeply superstitious man, ruled by his obsession with the occult.

Before his reign, witchcraft persecutions had been rare in Britain. But that all changed in 1590 when James personally oversaw the trials by torture for around seventy individuals implicated in the North Berwick Witch Trials, the biggest Scotland had known. The witches’ alleged crime? Raising a storm which nearly sank James’s ship when he sailed home from Norway with his new bride, Anne of Denmark. Possibly dozens of accused witches were executed by burning at the stake, although the precise number is unknown.