PART FOUR, Last in a series

Read Part One, Part Two, and Part Three

.

The late 16th and early 17th century was an era of radical social, economic, and religious change. As women had much to lose, they had reason to rebel. And they remained a threat to the new social order. Art of this period often depicted women as insubordinate and wanton: beating their husbands, swilling wine, and lustfully dragging men to bed (Merchant 133). Reformer John Knox was of the opinion that if a woman was presumptuous enough to rise above a man, she must be "repressed and bridled" (Ibid 145). This was one of the most bitterly misogynistic eras ever known.

Political and religious leaders seemed terrified by their fear that witches had organized themselves into a secret female society, as described in Kramer and Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum and King James's Daemonologie, among other works.

During witch trials, the witchfinders obsessively tried to force the accused to describe what went on at the alleged sabbat and to name the other women she had seen there. Georg Pictorious, a physician and scholar at the University of Freiburg in Germany, believed that witch persecutions were the only way humanity might be saved from these evil women. He maintained that if all the witches "are not burned, the number of these furies swells up in such an immense sea that no one could live safe from their spells and charms" (Midelfort 59).

In the 1970s and 1980s, some feminist historians such as Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English drew on Margaret Murray's study from the 1920s, The Witch Cult of Western Europe, to try to prove that there was indeed a secret society of women who practiced magic as part of an organized pagan cult. (See Ehrenreich and English's Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers)

While these speculations are very interesting, scant evidence exists to support this theory and most of it is based on torture-induced confessions.

It is, however, safe to state that people during the period of the witch persecutions sincerely believed and feared the existence of a secret female society.

Witches were believed to be a threat to both Christianity and to the middle class as it struggled to gain social authority (Hoher 46). The anti-puritan, plebian culture of lower class women stood in the way of the new values of the emerging bourgeois society. The stereotype of an organization of women out of control of society, women who cursed their enemies and mocked Christianity with their bizarre orgies, is perhaps indicative of an actual grain of reality behind the public fears. Hoher suggests that the rapidly changing society in Early Modern times, the role of the individual in a world that seemed increasingly confusing and uncertain, led to a collective insecurity--a fear that society would regress into old feudal traditions and chaos.

This fear was taken out brutally on those who would not integrate into the new order. The continuing disorder of the rural plebian culture and the refusal to conform to the new system took shape in the paranoia of the witch craze. Women, who according to Thomas Aquinas, Kramer, Sprenger, and others, were by nature weak-willed and sensual, were feared as the chief representatives of this rebellion--the chaos of uncontrolled nature and sexuality that must be subdued. Thus, it was these disorderly, uncontrollable women who were the most feared and hated. For the new order to survive, these women must be brutally exterminated (Ibid 42).

In examining the chronology of the witch trials, we see that the first trials targeted mainly poor, elderly women. As time went on and rich people and men started being accused, the witch hunts were considered to have got out of hand and they lost popular support. By this time, however, the new capitalism and religious order had been firmly established and the persecutions were no longer necessary.

This chronology reveals clearly what interests were at stake. The earliest trials of the 1560s focused almost exclusively on poor, older women. In the early trials of Wiesensteig and Rothenburg, 95 to 100% of the accused fit this stereotype. As the witch hunts progressed and the accused were tortured to name other witches, more and more men and upper class people were implicated (Midelfort 179). In Ellwangen in 1615, "accusations and convictions of highly placed and undoubtedly honorable men must have shaken people into recognizing that something had gone wrong" (Ibid 105).

Slowly the caricature of the witch as an old peasant woman was breaking down, "leaving society with no protective stereotypes, no sure way of telling who might be, and who could not be, a witch" (Ibid 182). Witch hunting so thoroughly shook up normal bonds of social trust that the most respected members of the community were no longer immune. The trials began to draw more and more criticism. Finally in 1672, the council of Altdorf in Schwaben declared all accusations of witchcraft illegal (Ibid 82). By this time, the persecutions had accomplished their original goal--the subjugation of rebellious lower class women and firmly entrenching those who survived the witch hunts into a subordinate domestic role. By the late 17th century we have no more illustrations of threatening, insubordinate women asserting their power.

Why this emphasis on poor and elderly women and why the last half of the 16th and first half of the 17th century? This period was crucial for the development of modern capitalism, a stricter moral code, and the placement of women into a narrowly defined domestic sphere, with utter economic dependence on their father or husband. The women who would most likely resist, at least in the early years of the persecutions, would be the older peasant women who remembered and clung to the old ways of plebian agrarian culture, the domestic economy, and the social and economic power they enjoyed. Such women would not easily relinquish their economic independence, their right of subsistence, or their personal freedom. The young woman beating her husband with her distaff, the symbol of her economic independence, in the early 16th century, became the old woman accused of witchcraft fifty years on. Note that in the 16th century illustrations I have included here, the old witch is depicted not with a broomstick but with her distaff.

Post-menopausal women were unburdened by pregnancies and childbirth. This gave them more freedom, time, and energy to stir up trouble. The accused witches' descriptions of the sabbat sound like the witch hunters' perversion of the joys of plebian peasant culture--drinking, dancing, and uninhibited celebration and sexuality. The earthly pleasures of the older generation became the evil heresy of the next. Since the descriptions of the alleged sabbat were drawn by torture, we must be cautious when drawing conclusions, but it makes a certain amount of sense in this historical context.

The women who had been strong, economically independent, and pleasure-loving members of the previous generation would not throw away their old privileges easily, so they became the witches of the new generation, a threat to society that had to be violently subdued for the new order to become established.

Sources:

Hoher, Friederike, "Hexe, Maria und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichket im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol III) Kuhn/Rusen, (eds.). Padagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Merchant, Carolyn, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Midelfort, Erik, H.C., Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations Stanford, 1972.

Ruether, Rosemary, New Woman/New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation, Seabury Press, New York, 1975.

Note: This essay was my Senior Paper I wrote in 1988 while an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota. Some of the sources may seem dated, but I think most of the history still stands up.

In recent years some serious scholars have revisited Margaret Murray's contention that there was indeed a secret female society in Europe during the period of the witch persecutions. See Carlo Ginzburg's book Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath and Emma Wilby's brilliant new book The Visions of Isobel Gowdie.

This website provides an interesting and well-researched view into medieval folk magic and possible pagan survivals in evidence before the beginning of the witch persecutions.

Showing posts with label reformation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label reformation. Show all posts

Sunday, 15 January 2012

Sunday, 23 October 2011

The Pendle Witches and Their Magic, Part 1

In 1612, in one of the most meticulously documented witch trials in English history, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest in Lancashire, Northern England were executed. In court clerk Thomas Potts’s account of the proceedings, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, published in 1613, he pays particular attention to the one alleged witch who escaped justice by dying in prison before she could come to trial. She was Elizabeth Southerns, more commonly known by her nickname, Old Demdike. According to Potts, she was the ringleader, the one who initiated all the others into witchcraft. This is how Potts describes her:

She was a very old woman, about the age of Foure-score yeares, and had been a Witch for fiftie yeares. Shee dwelt in the Forrest of Pendle, a vast place, fitte for her profession: What shee committed in her time, no man knows. . . . Shee was a generall agent for the Devill in all these partes: no man escaped her, or her Furies.

Quite impressive for an eighty-year-old lady! In England, unlike Scotland and Continental Europe, the law forbade the use of torture to extract witchcraft confessions. Thus the trial transcripts supposedly reveal Elizabeth Southerns’s voluntary confession, although her words might have been manipulated or altered by the magistrate and scribe. What’s interesting, if the trial transcripts can be believed, is that she freely confessed to being a healer and magical practitioner. Local farmers called on her to cure their children and their cattle. She described in rich detail how she first met her familiar spirit, Tibb, at the stone quarry near Newchurch in Pendle. He appeared to her at daylight gate—twilight in the local dialect—in the form of beautiful young man, his coat half black and half brown, and he promised to teach her all she needed to know about magic.

Tibb was not the “devil in disguise.” The devil, as such, appeared to be a minor figure in British witchcraft. It was the familiar spirit who took centre stage: this was the cunning person’s otherworldly spirit helper who could shapeshift between human and animal form, as Emma Wilby explains in her excellent scholarly study, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits. Mother Demdike describes Tibb appearing to her at different times in human form or in animal form. He could take the shape of a hare, a black cat, or a brown dog. It appeared that in traditional English folk magic, no cunning man or cunning woman could work magic without the aid of their spirit familiar—they needed this otherworldly ally to make things happen.

Belief in magic and the spirit world was absolutely mainstream in the 16th and 17th centuries. Not only the poor and ignorant believed in spells and witchcraft—rich and educated people believed in magic just as strongly. Dr. John Dee, conjuror to Elizabeth I, was a brilliant mathematician and cartographer and also an alchemist and ceremonial magician. In Dee’s England, more people relied on cunning folk for healing than on physicians. As Owen Davies explains in his book, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History, cunning men and women used charms to heal, foretell the future, and find the location of stolen property. What they did was technically illegal—sorcery was a hanging offence—but few were arrested for it as the demand for their services was so great. Doctors were so expensive that only the very rich could afford them and the “physick” of this era involved bleeding patients with lancets and using dangerous medicines such as mercury—your local village healer with her herbs and charms was far less likely to kill you.

In this period there were magical practitioners in every community. Those who used their magic for good were called cunning folk or charmers or blessers or wisemen and wisewomen. Those who were perceived by others as using their magic to curse and harm were called witches. But here it gets complicated. A cunning woman who performs a spell to discover the location of stolen goods would say that she is working for good. However, the person who claims to have been falsely accused of harbouring those stolen goods can turn around and accuse her of sorcery and slander. This is what happened to 16th century Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop of Edinburgh, cited by Emma Wilby in Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits. Dunlop was burned as a witch in 1576 after her “white magic” offended the wrong person. Ultimately the difference between cunning folk and witches lay in the eye of the beholder. If your neighbours turned against you and decided you were a witch, you were doomed.

Although King James I, author of the witch-hunting handbook Daemonologie, believed that witches had made a pact with the devil, there’s no actual evidence to suggest that witches or cunning folk took part in any diabolical cult. Anthropologist Margaret Murray, in her book, The Witch Cult in Western Europe, published in 1921, tried to prove that alleged witches were part of a Pagan religion that somehow survived for centuries after the Christian conversion. Most modern academics have rejected Murray’s hypothesis as unlikely. Indeed, lingering belief in an organised Pagan religion is very difficult to substantiate. So what did cunning folk like Old Demdike believe in?

Some of her family’s charms and spells were recorded in the trial transcripts and they reveal absolutely no evidence of devil worship, but instead use the ecclesiastical language of the Catholic Church, the old religion driven underground by the English Reformation. Her charm to cure a bewitched person, cited by the prosecution as evidence of diabolical sorcery, is, in fact, a moving and poetic depiction of the passion of Christ, as witnessed by the Virgin Mary. The text, in places, is very similar to the White Pater Noster, an Elizabethan prayer charm which Eamon Duffy discusses in his landmark book, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580.

It appears that Mother Demdike was a practitioner of the kind of quasi-Catholic folk magic that would have been commonplace before the Reformation. The pre-Reformation Church embraced many practises that seemed magical and mystical. People used holy water and communion bread for healing. They went on pilgrimages, left offerings at holy wells, and prayed to the saints for intercession. Some practises, such as the blessing of the wells and fields, may indeed have Pagan origins. Indeed, looking at pre-Reformation folk magic, it is very hard to untangle the strands of Catholicism from the remnants of Pagan belief, which had become so tightly interwoven.

Unfortunately Mother Demdike had the misfortune to live in a place and time when Catholicism was conflated with witchcraft. Even Reginald Scot, one of the most enlightened men of his age, believed the act of transubstantiation, the point in the Catholic mass where it is believed that the host becomes the body and blood of Christ, was an act of sorcery. In a 1645 pamphlet by Edward Fleetwood entitled A Declaration of a Strange and Wonderfull Monster, describing how a royalist woman in Lancashire supposedly gave birth to a headless baby, Lancashire is described thusly: "No part of England hath so many witches, none fuller of Papists." Keith Thomas’s social history Religion and the Decline of Magic is an excellent study on how the Reformation literally took the magic out of Christianity.

However, it would be an oversimplification to state that Mother Demdike was merely a misunderstood practitioner of Catholic folk magic. Her description of her decades-long partnership with her spirit Tibb seems to draw on something outside the boundaries of Christianity.

Although it is difficult to prove that witches and cunning folk in early modern Britain worshipped Pagan deities, the so-called fairy faith, the enduring belief in fairies and elves, is well documented. In his 1677 book The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, Lancashire author John Webster mentions a local cunning man who claimed that his familiar spirit was none other than the Queen of Elfhame herself. The Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop mentioned earlier, while being tried for witchcraft and sorcery at the Edinburgh Assizes, stated that her familiar spirit was a fairy man sent to her by the Queen of Elfhame.

Sunday, 16 October 2011

All Hallows Eve in Old Lancashire

Come Halloween, the popular imagination turns to witches. Especially in Pendle Witch Country, the rugged Pennine landscape surrounding Pendle Hill, once home to twelve individuals arrested for witchcraft in 1612. The most notorious was Elizabeth Southerns, alias Old Demdike, cunning woman of long-standing repute and the heroine of my novel Daughters of the Witching Hill.

How did these historical cunning folk celebrate All Hallows Eve?

All Hallows has its roots in the ancient feast of Samhain, which marked the end of the pastoral year and was considered particularly numinous, a time when the faery folk and the spirits of the dead roved abroad. Many of these beliefs were preserved in the Christian feast of All Hallows, which had developed into a spectacular affair by the late Middle Ages, with church bells ringing all night to comfort the souls thought to be in purgatory. Did this custom have its origin in much older rites of ancestor veneration? This threshold feast opening the season of cold and darkness allowed people to confront their deepest fears—that of death and what lay beyond. And their deepest longings—reunion with their cherished departed.

After the Reformation, these old Catholic rites were outlawed, resulting in one of the longest struggles waged by Protestant reformers against any of the traditional ecclesiastical rituals. Lay people stubbornly continued to hold vigils for their dead—a rite that could be performed without a priest and in cover of darkness. Until the early 19th century in the Lancashire parish of Whalley, some families still gathered at midnight upon All Hallows Eve. One person held a large bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the others knelt in a circle and prayed for their beloved dead until the flames burned out.

Long after the Reformation, people persisted in giving round oatcakes, called Soul-Mass Cakes to soulers, the poor who went door to door singing Souling Songs as they begged for alms on the Feast of All Souls, November 2. Each cake eaten represented a soul released from purgatory, a mystical communion with the dead.

In Glossographia, published in 1674, Thomas Blount writes:

All Souls Day, November 2d: the custom of Soul Mass cakes, which are a kind of oat cakes, that some of the richer sorts in Lancashire and Herefordshire (among the Papists there) use still to give the poor upon this day; and they, in retribution of their charity, hold themselves obliged to say this old couplet:

God have your soul,

Bones and all.

Other All Hallows folk rituals invoked the power of fire to purify and ward. In the Fylde district of Lancashire, farmers circled their fields with burning straw on the point of a fork to protect the coming crop from noxious weeds.

Fire was used to protect people from perceived evil spirits active on this night. At Longridge Fell in Lancashire, very close to Pendle Hill, the custom of ‘lating’ or hindering witches endured until the early 19th century. On All Hallows Eve, people walked up hillsides between 11 pm and midnight. Each person carried a lighted candle and if the flame went out, it was taken as a sign that an attack by a witch was impending and that the appropriate charms must be employed to protect oneself.

What do these old traditions mean to us today?

All Hallows is not just a date on the calendar, but the entire tide, or season, in which we celebrate ancestral memory and commemorate our dead. This is also the season of storytelling, of re-membering the past. The veil between the seen and unseen grows thin and we may dream true.

Wishing a blessed All Hallows Tide to all!

Source: Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain

Links:

Soul Cake Recipes

Souling Songs

Excerpt from Daughters of the Witching Hill

At Hallowtide, Liza insisted on walking up Blacko Hill, as we’d always done, for our midnight vigil on the Eve of All Saints. Under cover of darkness we crept forth with me carrying the lantern to light our way and John following with a pitchfork crowned in a great bundle of straw.

Once we reached the hilltop, after a furtive look round to make sure no one else was about, John lit the straw with the lantern flame so that the straw atop the pitchfork blazed like a torch. With him to hold the fork upright and keep an eye out for intruders, Liza and I knelt to pray for our dead. In the old days, we’d held this vigil in the church, the whole parish praying together, the darkened chapel bright as day with the many candles glowing on the saints’ altars. Now we were left to do this in secret, stealing away like criminals in the night, as though it were something shameful to hail our deceased. I prayed for my mam and grand-dad, calling out to their souls till I felt them both step through the veil to bring me comfort.

In my heart of hearts, I did not believe my loved ones were in purgatory waiting, by and by, to be let into heaven. There was no air of suffering or torment about them, only the joy of reunion. My mam, young and pretty, worked in her herb garden. She hummed a lilting tune whilst her earth-stained fingers pointed out to me the plants I must use to ease Liza’s birth pangs. Grand-Dad whispered his old charms to bless me and Liza and John.

A long spell I knelt there, held in the embrace of my beloved dead, till the straw on the pitchfork burned itself out, falling in embers and ash to the ground. Our John helped my pregnant daughter to her feet, then we made our way home through the night that no longer seemed so dark.

Labels:

all hallows,

holidays,

lancashire,

pendle witches,

reformation

Saturday, 27 August 2011

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change--Germany: 1560 - 1660

Burning witches, 1555.

PART THREE

(Read Part One and Part Two.)

Major witch hunting panics arose in the 1560s throughout Europe and were especially severe in the German Southwest. Who were the victims of this mass hysteria? Even though witches were believed to come from all social classes, the trials focused on poor, middle-aged or older women (Merchant 138). Throughout Europe, midwives and healers were particularly suspect. These "wise women" who healed with herbs were held especially suspect, as they were often older women who had astonishing empirical knowlege, which their accusers traced back to the devil (Rauer 121). Many other women were targeted, as well. Outsiders and women on the fringe of society were especially vulnerable. Fifty-five of the seventy-one accused witches executed in Rottenweil, Germany, after 1600 came from outside the community, and their execution reflected both xenophobia and "a hatred of the unusual and rootless" (Midelfort 95-96). The blatant persecution of the poor prompted one accused witch in Wiesenstieg to ask her inquisitor why rich women were never arrested (Ibid. 169). Thus, though the witch panics took different forms at different times and places, they never lost their essential character--that of a campaign of terror against lower class women in search of substinence.

The question we must ask when presented with this information is why poor women and why this period in history? To invoke such massive hunts, trials, and executions, these women must have been perceived as a major threat. Whose interests did their annihalation serve? Here, I must agree with Carolyn Merchant that the control and maintenance of the social order and women's place within it was one major underlying motivation for the witch trials (Merchant 138).

The women most likely to be accused and executed were those most visibly discontent with their socio-economic condition. They were the strident women who complained about their situations and would not conform to the increasingly restrictive sphere of femininity of 16th and 17th century Europe. Sharp-tongued mothers-in-law were accused of witchcraft by their own families. Feisty spinsters or widows who refused to remarry were frequent targets of witchcraft allegations. Midelfort cites an example of a widow accused of witchcraft being released on the condition that she live with her son-in-law and remain under his control (Midelfort 184). Another common trait found among accused witches in Southwest Germany was a melancholic dissatisfaction with marriage and conventional religion (Ibid. 92) Begging and complaining about poverty were behaviors that led very frequently to accusations (Rauer 121). In 1505, Heinrich Deichsler reports in his famous Nuernberger Chronik that Barbara, a woman from Schwabach near Nuremburg, was burned as a witch after she had borrowed money from several neighbors and failed to pay them back (Schneider 18-19). The primary personality traits of witches outlined by Kramer and Sprenger in their witch-hunting manual Malleus Maleficarum were infidelity, ambition, and lust--traits that may not have been so noteworthy a few centuries before (Malleus 47). All in all, witch persecutions appeared to focus specifically on headstrong and insubordinate women.

Once a woman was labeled a witch, almost anyone could do anything to her without fear or punishment. Legally she was damned and without rights. Even before she was arrested and taken to trial, her neighbors were allowed to take justice in their own hands. Indeed, neighbors took the lead in making witchcraft accusations--it was quite common to simply call someone one disliked a witch (Midelfort 115).

Once a witch was brought to trial, she was doomed. In Germany, torture was part of the established trial procedure and could legally last for days on end. German prison guards sometimes admitted to committing rape, extortion, and blackmail on prisoners, as well (Midelfort 107). Suspects were tortured until they confessed their participation in evil magic and sex with the devil, and named the other women they had seen at the supposed witches' sabbat. Many trial officials had lists of questions to elicit responses which would conform to established beliefs about witchcraft. Dr. Carl Ellwangen began his inquisitions by asking the accused to recite the Lord's Prayer. Then he immediately asked them who seduced them into witchcraft, how the seduction occured, why they gave in, what it was like to have sex with the devil, and so on (Ibid. 105). Torture could extract almost any confession from anyone. "When suspects proved stubborn, they were often tortured to death" (Ibid. 149). Another common trial procedure reveals the inquisitors' obsession with sexuality. Women were stripped, shaved, and pricked with bodkins all over their bodies in search of supposed witch marks, or searched for signs of intercourse with the devil. In Germany, it was not uncommon for an accused witch's property to be confiscated, with Church and secular authorities receiving their share (Ibid. 178). Because accused witches were tortured until they gave the names of others they had allegedly seen at the sabbat, the more intensely witchcraft was persecuted, and the more numerous the alleged witches became. Thus, the trials and accusations escalated (Trevor-Roper 97).

On a social level, witch persecutions could not only be used to weed out the most troublesome of the undeserving poor, but they also produced a general atmosphere of paranoia and disunity among the population. Even those who consulted accused witches for healing or other services risked becomong suspect (Larner 9). The accused witch served as an example to other women as to how they would be treated if they did as she did. This, of course, helped enforce new moral and religious codes (Ibid 102). For this reason, witch hunting can be viewed as one of the most public and effective forms of social control to evolve in Early Modern Europe (Ibid 64). Witches made convenient community scapegoats for communal misfortunes such as plagues and famines (Midelfort 121). The peasant population focused their anger and resentment at members of their own peer group rather than the ruling classes who exploited them. Thus, the witch persecutions undermined solidarity and cooperation among peasants and were instrumental in curbing rebellion. In Southwest Germany, the great witch trials began not long after the Peasant Wars.

Why were such extreme measures of social control necessary? What was taking place in society at large that caused poor and elderly women to be viewed as such an enormous threat?

The period of 1560 to 1660 was one of drastic economic, religious, and social change. This period witnessed the dissolution of the last remnants of a feudal agrarian and domestic economy in favor of a capitalist market economy (Hobsbawn 5). But for this new order to succeed, the old feudal tradition, in which peasants controlled production and were guaranteed subsistence, had to die. This transition was particularly hard on women. Formerly, in the domestic economy, the workplace was the home and women were active in cottage industries. However, the transition to working in outside the home made participation in this economy more and more difficult for women. Over this period, women were forced out of the guilds and the professions in which they could maintain economic independence. Increasingly they were forced into a narrowly domestic role. By the 16th century, the only opportunities for women to earn a living were in menial servant and labor occupations (Hoher 17). Often this sort of work was so low paid that women wandered penniless and homeless in search of better conditions (Ibid. 18).

Furthermore, by this time, even such traditionally feminine occupations such as healing and midwifery were being taken over by men. In the Renaissance, the trend among the wealthy was to have a university-educated physician at their disposal. After the advent of Paracelsus, the famous medical doctor, only men were officially allowed to practice medicine. Paracelsus himself explained that God granted the educated physician all the arts and faculties most beneficial to serve others and that the doctor must be a true man and not some ignorant old woman (Rauer 109, paraphrasing "So spricht Paracelsus"). Male medical practitioners went so far as to push women out of midwifery. Eucharius Rosslin, author of the foremost "midwife" book, Der Schwangererfrawen und Hebammen rossgarten complained that midwives' supposed incompetence, laziness, and lack of education resulted in high infant mortality. He even denounces them as murderers:

Ich meyn die Hebammen alle sampt

Die also gar kein Wissen handt.

Dazu durch yr Hynlessigkeit

Kind verderben weit und breit.

Und handt so schlechten Fleiss gethon

Dass sie mit Ampt eyn Mort begon. (Ibid 123)

Women in the Renaissance not only faced an economic crisis. Their sexual and social freedom was being severely restricted, as well. Unlike the Middle Ages, the Early Modern Period offered practically no alternative to the wife-mother role. By the 16th century, the beguinages were gone. Women hermits and vagabonds risked being accused of witchcraft. Due to the Reformation and Counter Reformation, even convents had grown smaller in number and the nuns who lived there experienced increasing restrictions on their mobility and contact to the outside world. At the same time, both Catholic and Protestant Churches were tightening moral strictures to produce a puritanism unheard of in the agrarian society of the medieval period. Church officials on both sides of the faultline of the Reformation wanted to have iron control over the moral behavior of the populace. Traditional seasonal festivals, hedonism, and sexual licentiousness all smacked of ungodliness and were no longer to be tolerated. Control over female sexuality was especially emphasized. Religious offences were now punished in secular courts and in public shaming rituals. For this was a period of great religious insecurity. The cut-throat competition between Catholics and Protestants resulted in sectarian and ideological warfare, with each side trying to terrorize the local population into submitting to their orthodoxies (Reuther 104). The witch trials' obsession with female sexuality reflects this puritanical attempt to control women's lives. Tightening religious strictures and the new economic system complemented each other--they both attempted to bring the rebellious, hedonistic peasant population under control of Church and secular authorities. The witch persecutions were symptomatic of a new totalitarianism (Rauer 123).

The ideal housewife, circa 1525, by Anton Woensam.

Sources:

Hobsbawn, E.J., "The Crisis in the Seventeenth Century," Crisis in Europe 1560-1660, Trevor Aston, ed., Routledge, London, 1983.

Hoher, Frederike, "Hexe, Maria, und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichkeit im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte, Vol. III, Kuhn/Rusen, eds, Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Duesseldorf, 1983.

Institorus, Henricus, Malleus Maleficarum, Benjamin Blom, Inc., New York, 1970.

Larner, Christine, Enemies of God, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1981.

Merchant, Carolyn, The Death of Nature: Women Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Haeprer & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Midelfort, Erik, H.C., Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations, Stanford, 1972.

Rauer, Brigitte, "Hexenwahn--Frauenverfolgung zu Beginn der Neuzeit," Frauen in der Geschichte, Vol. II, Kuhn/Rusen, eds., Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, 1982.

Schneider, Joachim, Heinrich Deichsler und die Nuernberger Chronik des 15. Jahrhunderts, Wissenliteratur im Mittelalter, Vol. 5, Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1991.

Trevor-Roper, H.R., The European Witch-Craze of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Harper & Row, New York, 1969.

Tuesday, 26 October 2010

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change--Germany: 1560 - 1660

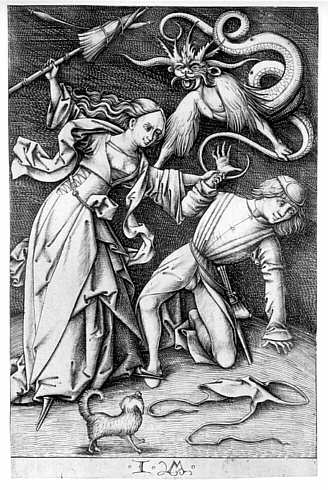

"The Evil Wife" by Israhel van Meckenem, 1440/1445-1503

A woman, encouraged by a demon, beats her husband with her distaff.

PART TWO

By the latter half of the 15th century, the feudal agrarian economy was beginning to crumble, while the capitalist market economy was growing more and more powerful, as did economic competition between men and women. Men active in the market economy tried to further their interests by simultaneously excluding women from many professions and trying to marginalize the domestic economy by claiming that home-produced goods were inferior to shop-produced goods. The guilds also began excluding women. Feeling their livelihood threatened by the competition with wealthy burghers, who set up their own industries and arranged for peasants to manufacture goods for them, male guild members struggled to initiate restrictions for women in the guilds. In 1494 in Cologne, for example, women were driven out of the harness-making guild for the first time. (Rauer 108).

In addition, traditionally "female" professions such as medicine were being taken over by men; male doctors had grown popular among the wealthy classes and were now also making inroads on medical care for the lower classes, and even encroaching on the very traditionally feminine occupation of midwifery (Ehrenreich and English 15-16--please note that the scholarship of this particular text has been called into question). Now we see the beginning of the sexual division of labor: women were beginning to be pushed into the ever-shrinking domestic economy, while men attempted to make the market economy their exclusive domain. This trend not only effected women on a purely economic level, but it also had a profound effect on women's social and sexual status. "The contraction and redefinition of women's productive and domestic roles was consistent with changes in the ideology of sexuality" (Merchant 150).

The Renaissance also ushered in a new ideal of bourgeois womanhood. The domestic sphere of the housewife and mother was idealized by Protestant intellectuals such as Martin Luther. "Gott hat Mann und Frau geschaffen, das Weib zum Mehren mit Kinder tragen; den Mann zum Naehren und Wehren," the Father of the Reformation wrote, advocating strict gender roles. "Im weltlichen politischen Regiment und Handeln antugen sie [Frauen] nichts, dazu sind Maenner geschaffen und geordnet von Gott, nicht die Weiber" (Rauer 112-113). (God created man and woman so that the woman would bear children and that the man would provide and defend. In worldly politics and trade, women should have no part--God created and ordained men for this, not women.) It must, however, be pointed out that Luther's own wife, the ex-nun Katharina von Bora was a very strong woman, beloved by her husband, who addressed her as "Herrin," or "my boss." She took charge of their household finances, farmed, raised and slaughtered livestock, and brewed vast quantities of beer to support Luther and his theology students and keep their household fed. She was the sole woman to take part in Luther's otherwise exclusively male "table talk" discussions.

Despite the positive recognition of woman as wife and mother that took place in the early Reformation, the misogynist ideology of the Catholic Church, such as Thomas Aquinas's contention that women are by nature morally weaker than men, remained in both Catholic and Protestant Churches. Also, Renaissance humanism pushed upper class women into the narrow role of being well-educated but submissive helpmates to their scholarly husbands. In 1499, Konrad Reutinger extolled his wife as the perfect Renaissance woman:

habe ich als Gattin ein Maedchen heimgefuehrt . . . schamhaft, bescheiden, schoen, etwas erfahren in den lateinischen Wissenschaften, die nie von ihren Hausgenossen streit- order schmaehsuechtig gesehen worden ist . . . . Daher weiss ich dem besten und groessten Gott jetzt und in Zukunft Dank, der meinem Studium eine Gefaehrtin und Anhaengerin gegeben hat, die mir aufs innigste vertraut ist. (Ibid 133)

(I've taken a girl home to be my wife [who is] modest, docile, beautiful, with some knowledge of Latin that those in her household have never come to view as overly ambitious or aggressive . . . . For this I thank the best and greatest God now and always, that he has given me for my studies a companion and follower in whom I trust absolutely.)

The Renaissance also saw the birth of a brand new bourgeois motherhood ideal. In the Middle Ages, mothers were expected to take care of their young children, but the mother-child bond was not as glorified to an almost sacred institution and be-all and end-all of a woman's existence as it would become in later centuries. Also, childhood, as we now view it, did not exist then; children were treated as small adults. Children of the lower classes who survived infant hunger and childhood diseases were sent away from their parents as soon as they were old enough to find work as servants in the wealthier estates (Hoher 20).

In the second half of the 15th century, the Catholic Church was losing its authority, under threat by serious challenges and dissent that would soon take the shape of the Reformation. During this divisive time, the Catholic Church expressed a new kind of religious aggression in enforcing morality and a new fascination with the devil. The hedonism that had reigned in medieval plebeian culture was no longer to be benignly overlooked. Wifely obedience in marriage began to be emphasized more and more. During this period, a new genre of literature originated: the Devil Book, which concentrated on explaining how certain activities, such as dancing and drinking, were sinful. The general effect of these publications was to imply that the devil was everywhere (Midelfort 69). The Catholic Church's attitude towards witchcraft also changed quite significantly--the ancient code saying it was sinful to believe in witches was reversed; now Church officials declared it sinful not to believe in them. They argued that a new sect had developed, which even the Fathers of the Church had been unable to foresee (Chamberlin 137). In 1484, Pope Innocent and two German Dominican friars, Kramer and Sprenger, issued a bull against witchcraft in response to rumors of widespread witch activity in Germany. This bull granted the use of inquisitorial techniques in witch hunting. Although the late 15th century was noted for religious intolerance, it was also characterized by a "new carelessness in law" (Ibid 69). The use of torture was revived with the re-establishment of Roman Law. This resulted in a considerable escalation in witch persecutions: "Torture allowed accusations to proliferate to epidemic proportions, because once a witch confessed under torture, she would be tortured again to divulge the names of her neighbors seen at the Sabbat" (Ruether 102). In 1486, Kramer and Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum was published. This highly misogynistic witch-hunting manual established the belief that women are by nature more prone to witchcraft than men: "Femina comes from Fe [faith] and Minus, since she is ever weaker to hold the faith . . . . Therefore, a wicked woman is by her nature quicker to waver in her faith, and consequently quicker to abjure the faith, which is the root of witchcraft" (Malleus 44). The authors of the book were also obsessed with the idea that the unquenchable carnal lust of women drove them to the devil: "All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which in women is insatiable . . . . Wherefore for the sake of fulfilling their lusts they consort with devils . . . it is sufficiently clear that it is no matter for wonder that there are more women than men infected with the heresy of witchcraft (Ibid 43).

As we have seen, women were beginning to be perceived as a threat to the new economic and religious developments. One cannot imagine that they were at all cooperative with the new infringements on the relative economic and sexual freedom they had enjoyed in the past. They would not submit easily to these changes--they would resist--and their resistance would make them a threat to the interests of the new order. In the arts and media of this period, women were constantly portrayed as domineering, threatening, lustful, violent, and powerful: a force that must be quelled. Village festivals of this period often had floats featuring wives beating their husbands, hurling refuse and rocks at them, and verbally abusing them. Numerous art works of this era, especially the works of Hans Baldung Grien and Albrecht Duerer, depicted the supposed disorder wrought by lusty women. Popular illustrations portrayed women beating their husbands with distaffs. Spinning was one of the occupations with which a woman could still make a decent living. The distaff symbolized her earning power and economic independence from her husband. These male artists interpreted woman's breadwinning power as something threatening, something she abused: her pride of being able to earn undermined her husband's authority. These women were not conforming to the new mold of wifely obedience that Church officials were stressing more and more. Thus, not only were women a threat to their husband's authority, they were also a threat to society in general.

One 1521 engraving by Urs Graf (unfortunately I could not find a jpeg of it to post here) depicts two young women savagely beating a monk who has probably molested them. In the Renaissance, women were portrayed as capable of violence, revenge, and self-defense. Urs Graf's women respect neither male nor religious authority; they assume the right to punish any man who tries to molest them. Hans Baldung Grien's engraving, "Aristotle and Phyllis," below, shows the legendary Phyllis literally making an ass of Aristotle. In all these pictures, women are portrayed as violent, crafty, and insubordinate. Their male victims are portrayed as pathetic, weak-willed fools for allowing themselves to be dominated by women. The message that I read into these art works is that women are trying to hold the upper hand. They will not allow themselves to be forced into the new "proper" feminine sphere. In order for women to be put in their place, men must assert their dominance. Thus, these male artists perceive women as a powerful, chaotic force that needed to be violently subdued. This violence against women would not be long in coming.

"Hercules among the maids of Queen Omphale" by Lucus Cranach the Elder: these women are emasculating the mighty Hercules by dressing him in a women's coif and pressing a distaff into his hand.

"Aristotle and Phyllis" by Hans Baldung Grien, 1513.

Aristotle who proclaimed that the male is superior to the female is shown subjected to Phyllis who literally makes an ass of him.

Labels:

art,

reformation,

renaissance,

witchcraft,

women's history

Sunday, 19 September 2010

Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus

In the witch trials that raged across Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, legal authorities strove to uncover evidence of a pact between the accused witch and the devil. But did this alleged pact ever exist except in the imaginations of the witchfinders?

The legend of Doctor Faustus captivated the public because it purported to reveal the story of real-life German magician, alchemist, and astronomer, Johann Georg Faust, who died in 1540. Rumour had it that his powers were given to him by the devil. His legend first appeared in print in a 1587 chapbook, Das Faustbuch, a cautionary tale of how the unbridled pursuit of knowledge can undermine religious salvation.

Inspired by this pamphlet, Christopher Marlowe (1554-1593) penned his masterpiece, The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus, the first surviving published copy of which is dated 1604. No simple moral tale, Marlowe's tragedy works on a number of levels.

Set in Wittenberg, Germany, the great humanistic centre of learning and the cradle of the Reformation, Marlowe's Faustus is a low born man who has become a respected Doctor of Philosophy at the university. But this is not enough. He would have absolute knowledge, absolute power. And so he turns to the dark arts. Casting a circle, he abjures the name of God and summons a demon, Mephistopheles. Under Mephistopheles's direction, Faustus then makes his pact with the devil, signing it in his own blood. He strikes a hard bargain. For twenty-four years, Faustus will do whatever he wants, with Mephistopheles as his obedient servant. When his time is up, Lucifer will summon Faustus to hell.

While the party lasts, Faustus lives it up. The middle of the play is full of schoolboy pranks. His horse is an enchanted hay bale which he sells to a hapless tavern keeper for fifty thalers. Mephistopheles spirits Faustus to the Vatican so that he can mock the pope and cardinals. When the pontiff and his men try to exorcise Faustus and his host of demons with bell, book, and candle, they find they cannot. In Marlowe's play, the pope is depicted as powerless to expel evil because he himself is corrupted and damned. Marlowe's own anti-Catholicism is well documented. While a student at Corpus Christi College in Cambridge, he served as a government spy, infilitrating Catholic circles to uncover plots against Queen Elizabeth I.

At the Emperor's court, Faustus conjures Alexander the Great and his paramour. He even manages to conjure up the spirit of Helen of Troy.

Yet when all these merry japes are over, Faustus finds himself utterly alone and bereft, forced to face the full weight of his pact. Though he desperately seeks redemption, he never achieves it and so quietly resigns himself to his coffin where he awaits his damnation.

Moral interpretations of the play are complicated by the Protestant teachings of Marlowe's era that insisted it was impossible for the individual to save his or her own soul. Calvin preached the doctrine of predestination, namely that God had already determined who was damned and who was saved, without any reference to the person's virtue or deeds. Seen through this lens, Faustus is not damned because he sold his soul to the devil. No, he is a clever Renaissance man who strikes this bargain because he has already been damned by his own God; our hero wants to at least enjoy some pleasure and self-determination in this earthly life before his inevitable eternity in hell. In witnessing Faustus's yearning and failure to achieve redemption are we seeing the devastating implications of Calvinist dogma?

Marlowe's Doctor Faustus was a sensation when it was first performed, scandalizing its audience by featuring forbidden acts of conjuration and blasphemy on stage.

Marlowe himself is a shadowy figure. In London, he kept the company of mathematicians, poets, and scientists, who gathered in a secret School of Night. Did Marlowe himself indulge in the dark arts? We will never know.

On May 30, 1593, the playwright, previously arrested on charges of brawling and duelling, became embroiled in a dispute with a tavern keeper over his bill. This escalated into a full blown knife fight, resulting in the playwright's death. He was twenty-nine years old.

Around this time, a note delivered to the authorities stated that Marlowe was an atheist who believed "that the first beginning of Religion was only to keep men in awe." But it is impossible to judge the veracity of this claim. Marlowe the man remains as shrouded in mystery as the legendary Faustus himself.

It's interesting to contrast Marlowe's Faustus to the version by Goethe, the great German Romantic. Goethe, who studied philosophy, alchemy, mysticism, and natural magic, appeared to have felt a great deal of sympathy with Faustus. Instead of demonising him, he invites us to identify with his protagonist's tireless quest to understand the mysteries of existence. Significantly, Goethe's Faustus receives redemption. Angels carry him off to heaven before Mephistopheles can drag him down to hell.

Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre's production of Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus was absolutely magical, making maximum use of the circular stage to create the magic circle around which the audience hovers, as though we are spectral witnesses to Faustus's damnation.

This is no dry production but an enchanting pageant meant to capture the Elizabethan sense of awe at the magic taking place before us.

Lucifer (actor Gwendoline Christie) appears as a woman in glittering chainmail, who flies down from the ceiling on a trapeze. The actor appears to have great fun with her role, cackling and lounging on Faustus's desk while he mourns his doom and the impossibility of redemption.

A host of twenty four extras play the part of spirits, demons, and courtiers, mingling with the audience before descending on ladders onto the stage. Huge puppets appear as the host of Seven Deadly Sins. Faustus even engages in actual stage conjuring. But at the centre of it all is the powerful chemistry between Patrick O'Kane, who plays the volatile Faustus, and the quiet understatement of Ian Redford's Mephistopheles, who appears as an unassuming old man in a vicar's suit.

Ultimately the play is a powerful meditation on free will and the soul, and how willing people are to sacrifice their soul for fleeting ambition.

My husband, who saw the play with me, observed that in the modern corporate world, people sell their souls for a lot less than Doctor Faustus, who had least had some fun while the party lasted.

Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre's production of Doctor Faustus runs until October 9.

Dr. Naomi Baker's essay on Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)