PART FOUR, Last in a series

Read Part One, Part Two, and Part Three

.

The late 16th and early 17th century was an era of radical social, economic, and religious change. As women had much to lose, they had reason to rebel. And they remained a threat to the new social order. Art of this period often depicted women as insubordinate and wanton: beating their husbands, swilling wine, and lustfully dragging men to bed (Merchant 133). Reformer John Knox was of the opinion that if a woman was presumptuous enough to rise above a man, she must be "repressed and bridled" (Ibid 145). This was one of the most bitterly misogynistic eras ever known.

Political and religious leaders seemed terrified by their fear that witches had organized themselves into a secret female society, as described in Kramer and Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum and King James's Daemonologie, among other works.

During witch trials, the witchfinders obsessively tried to force the accused to describe what went on at the alleged sabbat and to name the other women she had seen there. Georg Pictorious, a physician and scholar at the University of Freiburg in Germany, believed that witch persecutions were the only way humanity might be saved from these evil women. He maintained that if all the witches "are not burned, the number of these furies swells up in such an immense sea that no one could live safe from their spells and charms" (Midelfort 59).

In the 1970s and 1980s, some feminist historians such as Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English drew on Margaret Murray's study from the 1920s, The Witch Cult of Western Europe, to try to prove that there was indeed a secret society of women who practiced magic as part of an organized pagan cult. (See Ehrenreich and English's Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers)

While these speculations are very interesting, scant evidence exists to support this theory and most of it is based on torture-induced confessions.

It is, however, safe to state that people during the period of the witch persecutions sincerely believed and feared the existence of a secret female society.

Witches were believed to be a threat to both Christianity and to the middle class as it struggled to gain social authority (Hoher 46). The anti-puritan, plebian culture of lower class women stood in the way of the new values of the emerging bourgeois society. The stereotype of an organization of women out of control of society, women who cursed their enemies and mocked Christianity with their bizarre orgies, is perhaps indicative of an actual grain of reality behind the public fears. Hoher suggests that the rapidly changing society in Early Modern times, the role of the individual in a world that seemed increasingly confusing and uncertain, led to a collective insecurity--a fear that society would regress into old feudal traditions and chaos.

This fear was taken out brutally on those who would not integrate into the new order. The continuing disorder of the rural plebian culture and the refusal to conform to the new system took shape in the paranoia of the witch craze. Women, who according to Thomas Aquinas, Kramer, Sprenger, and others, were by nature weak-willed and sensual, were feared as the chief representatives of this rebellion--the chaos of uncontrolled nature and sexuality that must be subdued. Thus, it was these disorderly, uncontrollable women who were the most feared and hated. For the new order to survive, these women must be brutally exterminated (Ibid 42).

In examining the chronology of the witch trials, we see that the first trials targeted mainly poor, elderly women. As time went on and rich people and men started being accused, the witch hunts were considered to have got out of hand and they lost popular support. By this time, however, the new capitalism and religious order had been firmly established and the persecutions were no longer necessary.

This chronology reveals clearly what interests were at stake. The earliest trials of the 1560s focused almost exclusively on poor, older women. In the early trials of Wiesensteig and Rothenburg, 95 to 100% of the accused fit this stereotype. As the witch hunts progressed and the accused were tortured to name other witches, more and more men and upper class people were implicated (Midelfort 179). In Ellwangen in 1615, "accusations and convictions of highly placed and undoubtedly honorable men must have shaken people into recognizing that something had gone wrong" (Ibid 105).

Slowly the caricature of the witch as an old peasant woman was breaking down, "leaving society with no protective stereotypes, no sure way of telling who might be, and who could not be, a witch" (Ibid 182). Witch hunting so thoroughly shook up normal bonds of social trust that the most respected members of the community were no longer immune. The trials began to draw more and more criticism. Finally in 1672, the council of Altdorf in Schwaben declared all accusations of witchcraft illegal (Ibid 82). By this time, the persecutions had accomplished their original goal--the subjugation of rebellious lower class women and firmly entrenching those who survived the witch hunts into a subordinate domestic role. By the late 17th century we have no more illustrations of threatening, insubordinate women asserting their power.

Why this emphasis on poor and elderly women and why the last half of the 16th and first half of the 17th century? This period was crucial for the development of modern capitalism, a stricter moral code, and the placement of women into a narrowly defined domestic sphere, with utter economic dependence on their father or husband. The women who would most likely resist, at least in the early years of the persecutions, would be the older peasant women who remembered and clung to the old ways of plebian agrarian culture, the domestic economy, and the social and economic power they enjoyed. Such women would not easily relinquish their economic independence, their right of subsistence, or their personal freedom. The young woman beating her husband with her distaff, the symbol of her economic independence, in the early 16th century, became the old woman accused of witchcraft fifty years on. Note that in the 16th century illustrations I have included here, the old witch is depicted not with a broomstick but with her distaff.

Post-menopausal women were unburdened by pregnancies and childbirth. This gave them more freedom, time, and energy to stir up trouble. The accused witches' descriptions of the sabbat sound like the witch hunters' perversion of the joys of plebian peasant culture--drinking, dancing, and uninhibited celebration and sexuality. The earthly pleasures of the older generation became the evil heresy of the next. Since the descriptions of the alleged sabbat were drawn by torture, we must be cautious when drawing conclusions, but it makes a certain amount of sense in this historical context.

The women who had been strong, economically independent, and pleasure-loving members of the previous generation would not throw away their old privileges easily, so they became the witches of the new generation, a threat to society that had to be violently subdued for the new order to become established.

Sources:

Hoher, Friederike, "Hexe, Maria und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichket im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol III) Kuhn/Rusen, (eds.). Padagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Merchant, Carolyn, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Midelfort, Erik, H.C., Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations Stanford, 1972.

Ruether, Rosemary, New Woman/New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation, Seabury Press, New York, 1975.

Note: This essay was my Senior Paper I wrote in 1988 while an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota. Some of the sources may seem dated, but I think most of the history still stands up.

In recent years some serious scholars have revisited Margaret Murray's contention that there was indeed a secret female society in Europe during the period of the witch persecutions. See Carlo Ginzburg's book Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath and Emma Wilby's brilliant new book The Visions of Isobel Gowdie.

This website provides an interesting and well-researched view into medieval folk magic and possible pagan survivals in evidence before the beginning of the witch persecutions.

Showing posts with label women's history. Show all posts

Showing posts with label women's history. Show all posts

Sunday, 15 January 2012

Saturday, 27 August 2011

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change--Germany: 1560 - 1660

Burning witches, 1555.

PART THREE

(Read Part One and Part Two.)

Major witch hunting panics arose in the 1560s throughout Europe and were especially severe in the German Southwest. Who were the victims of this mass hysteria? Even though witches were believed to come from all social classes, the trials focused on poor, middle-aged or older women (Merchant 138). Throughout Europe, midwives and healers were particularly suspect. These "wise women" who healed with herbs were held especially suspect, as they were often older women who had astonishing empirical knowlege, which their accusers traced back to the devil (Rauer 121). Many other women were targeted, as well. Outsiders and women on the fringe of society were especially vulnerable. Fifty-five of the seventy-one accused witches executed in Rottenweil, Germany, after 1600 came from outside the community, and their execution reflected both xenophobia and "a hatred of the unusual and rootless" (Midelfort 95-96). The blatant persecution of the poor prompted one accused witch in Wiesenstieg to ask her inquisitor why rich women were never arrested (Ibid. 169). Thus, though the witch panics took different forms at different times and places, they never lost their essential character--that of a campaign of terror against lower class women in search of substinence.

The question we must ask when presented with this information is why poor women and why this period in history? To invoke such massive hunts, trials, and executions, these women must have been perceived as a major threat. Whose interests did their annihalation serve? Here, I must agree with Carolyn Merchant that the control and maintenance of the social order and women's place within it was one major underlying motivation for the witch trials (Merchant 138).

The women most likely to be accused and executed were those most visibly discontent with their socio-economic condition. They were the strident women who complained about their situations and would not conform to the increasingly restrictive sphere of femininity of 16th and 17th century Europe. Sharp-tongued mothers-in-law were accused of witchcraft by their own families. Feisty spinsters or widows who refused to remarry were frequent targets of witchcraft allegations. Midelfort cites an example of a widow accused of witchcraft being released on the condition that she live with her son-in-law and remain under his control (Midelfort 184). Another common trait found among accused witches in Southwest Germany was a melancholic dissatisfaction with marriage and conventional religion (Ibid. 92) Begging and complaining about poverty were behaviors that led very frequently to accusations (Rauer 121). In 1505, Heinrich Deichsler reports in his famous Nuernberger Chronik that Barbara, a woman from Schwabach near Nuremburg, was burned as a witch after she had borrowed money from several neighbors and failed to pay them back (Schneider 18-19). The primary personality traits of witches outlined by Kramer and Sprenger in their witch-hunting manual Malleus Maleficarum were infidelity, ambition, and lust--traits that may not have been so noteworthy a few centuries before (Malleus 47). All in all, witch persecutions appeared to focus specifically on headstrong and insubordinate women.

Once a woman was labeled a witch, almost anyone could do anything to her without fear or punishment. Legally she was damned and without rights. Even before she was arrested and taken to trial, her neighbors were allowed to take justice in their own hands. Indeed, neighbors took the lead in making witchcraft accusations--it was quite common to simply call someone one disliked a witch (Midelfort 115).

Once a witch was brought to trial, she was doomed. In Germany, torture was part of the established trial procedure and could legally last for days on end. German prison guards sometimes admitted to committing rape, extortion, and blackmail on prisoners, as well (Midelfort 107). Suspects were tortured until they confessed their participation in evil magic and sex with the devil, and named the other women they had seen at the supposed witches' sabbat. Many trial officials had lists of questions to elicit responses which would conform to established beliefs about witchcraft. Dr. Carl Ellwangen began his inquisitions by asking the accused to recite the Lord's Prayer. Then he immediately asked them who seduced them into witchcraft, how the seduction occured, why they gave in, what it was like to have sex with the devil, and so on (Ibid. 105). Torture could extract almost any confession from anyone. "When suspects proved stubborn, they were often tortured to death" (Ibid. 149). Another common trial procedure reveals the inquisitors' obsession with sexuality. Women were stripped, shaved, and pricked with bodkins all over their bodies in search of supposed witch marks, or searched for signs of intercourse with the devil. In Germany, it was not uncommon for an accused witch's property to be confiscated, with Church and secular authorities receiving their share (Ibid. 178). Because accused witches were tortured until they gave the names of others they had allegedly seen at the sabbat, the more intensely witchcraft was persecuted, and the more numerous the alleged witches became. Thus, the trials and accusations escalated (Trevor-Roper 97).

On a social level, witch persecutions could not only be used to weed out the most troublesome of the undeserving poor, but they also produced a general atmosphere of paranoia and disunity among the population. Even those who consulted accused witches for healing or other services risked becomong suspect (Larner 9). The accused witch served as an example to other women as to how they would be treated if they did as she did. This, of course, helped enforce new moral and religious codes (Ibid 102). For this reason, witch hunting can be viewed as one of the most public and effective forms of social control to evolve in Early Modern Europe (Ibid 64). Witches made convenient community scapegoats for communal misfortunes such as plagues and famines (Midelfort 121). The peasant population focused their anger and resentment at members of their own peer group rather than the ruling classes who exploited them. Thus, the witch persecutions undermined solidarity and cooperation among peasants and were instrumental in curbing rebellion. In Southwest Germany, the great witch trials began not long after the Peasant Wars.

Why were such extreme measures of social control necessary? What was taking place in society at large that caused poor and elderly women to be viewed as such an enormous threat?

The period of 1560 to 1660 was one of drastic economic, religious, and social change. This period witnessed the dissolution of the last remnants of a feudal agrarian and domestic economy in favor of a capitalist market economy (Hobsbawn 5). But for this new order to succeed, the old feudal tradition, in which peasants controlled production and were guaranteed subsistence, had to die. This transition was particularly hard on women. Formerly, in the domestic economy, the workplace was the home and women were active in cottage industries. However, the transition to working in outside the home made participation in this economy more and more difficult for women. Over this period, women were forced out of the guilds and the professions in which they could maintain economic independence. Increasingly they were forced into a narrowly domestic role. By the 16th century, the only opportunities for women to earn a living were in menial servant and labor occupations (Hoher 17). Often this sort of work was so low paid that women wandered penniless and homeless in search of better conditions (Ibid. 18).

Furthermore, by this time, even such traditionally feminine occupations such as healing and midwifery were being taken over by men. In the Renaissance, the trend among the wealthy was to have a university-educated physician at their disposal. After the advent of Paracelsus, the famous medical doctor, only men were officially allowed to practice medicine. Paracelsus himself explained that God granted the educated physician all the arts and faculties most beneficial to serve others and that the doctor must be a true man and not some ignorant old woman (Rauer 109, paraphrasing "So spricht Paracelsus"). Male medical practitioners went so far as to push women out of midwifery. Eucharius Rosslin, author of the foremost "midwife" book, Der Schwangererfrawen und Hebammen rossgarten complained that midwives' supposed incompetence, laziness, and lack of education resulted in high infant mortality. He even denounces them as murderers:

Ich meyn die Hebammen alle sampt

Die also gar kein Wissen handt.

Dazu durch yr Hynlessigkeit

Kind verderben weit und breit.

Und handt so schlechten Fleiss gethon

Dass sie mit Ampt eyn Mort begon. (Ibid 123)

Women in the Renaissance not only faced an economic crisis. Their sexual and social freedom was being severely restricted, as well. Unlike the Middle Ages, the Early Modern Period offered practically no alternative to the wife-mother role. By the 16th century, the beguinages were gone. Women hermits and vagabonds risked being accused of witchcraft. Due to the Reformation and Counter Reformation, even convents had grown smaller in number and the nuns who lived there experienced increasing restrictions on their mobility and contact to the outside world. At the same time, both Catholic and Protestant Churches were tightening moral strictures to produce a puritanism unheard of in the agrarian society of the medieval period. Church officials on both sides of the faultline of the Reformation wanted to have iron control over the moral behavior of the populace. Traditional seasonal festivals, hedonism, and sexual licentiousness all smacked of ungodliness and were no longer to be tolerated. Control over female sexuality was especially emphasized. Religious offences were now punished in secular courts and in public shaming rituals. For this was a period of great religious insecurity. The cut-throat competition between Catholics and Protestants resulted in sectarian and ideological warfare, with each side trying to terrorize the local population into submitting to their orthodoxies (Reuther 104). The witch trials' obsession with female sexuality reflects this puritanical attempt to control women's lives. Tightening religious strictures and the new economic system complemented each other--they both attempted to bring the rebellious, hedonistic peasant population under control of Church and secular authorities. The witch persecutions were symptomatic of a new totalitarianism (Rauer 123).

The ideal housewife, circa 1525, by Anton Woensam.

Sources:

Hobsbawn, E.J., "The Crisis in the Seventeenth Century," Crisis in Europe 1560-1660, Trevor Aston, ed., Routledge, London, 1983.

Hoher, Frederike, "Hexe, Maria, und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichkeit im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte, Vol. III, Kuhn/Rusen, eds, Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Duesseldorf, 1983.

Institorus, Henricus, Malleus Maleficarum, Benjamin Blom, Inc., New York, 1970.

Larner, Christine, Enemies of God, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1981.

Merchant, Carolyn, The Death of Nature: Women Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Haeprer & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Midelfort, Erik, H.C., Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations, Stanford, 1972.

Rauer, Brigitte, "Hexenwahn--Frauenverfolgung zu Beginn der Neuzeit," Frauen in der Geschichte, Vol. II, Kuhn/Rusen, eds., Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, 1982.

Schneider, Joachim, Heinrich Deichsler und die Nuernberger Chronik des 15. Jahrhunderts, Wissenliteratur im Mittelalter, Vol. 5, Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1991.

Trevor-Roper, H.R., The European Witch-Craze of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Harper & Row, New York, 1969.

Thursday, 4 August 2011

Women & the Crusades: guest post by Nan Hawthorne

Today's guest post is by Nan Hawthorne, whose new novel Beloved Pilgrim explores the Crusade of 1101 from the perspective of a woman who went off to fight.

During my own research of Hildegard von Bingen, I uncovered this short description of female crusaders from the Disibodenberg Chronicles, written by the monks of the abbey of Disibodenberg where Hildegard lived from the age of eight as a child anchorite:

Not only men and boys, but many women also took part in this journey. Indeed females went forth on this venture dressed as men and marched in armour . . .

--From the Disibodenberg Chronicles, as cited by Fiona Maddocks in her book, Hildegard of Bingen: The Woman of Her Age.

Although the fiction might be romantic and compelling, we can't neglect certain historical realities. Muslims and Jews regarded these "Holy Wars" as genocide. Indeed, in Rhineland German cities and towns such as Mainz and Bacharach, many Jewish people met their deaths in the tumult of the crusading fervour.

The Crusade of 1101 and Beloved Pilgrim by Nan Hawthorne

The initial research I did to write, Beloved Pilgrim, had everything to do with my choice of the dates and events portrayed. Though many of us are familiar with battles and figures from the Crusades, the Crusade of 1101, though obscure by comparison, proved to be tailor-made for a novel. The actual event took place over only a few months and in itself was classic plotting, with a dramatic beginning, several setbacks, conflict not only between the crusaders and Turks but also between the Christian leaders who made such a mess of things, and the devastating conclusion. Reading more about the crusade, usually considered an extension of the First Crusade, I found that the context was ideal for character development and thematic requirements I already had in mind.

The chroniclers of this crusade did not experience it themselves, but scholar Steven Runciman was able to put together what is as close to a definitive history as possible. His work, A History of the Crusades: Volumes 1-3, was my and the rest of the world’s primary source, along with the able help of Jack Graham, a medieval warfare enthusiast who helped me choreograph battle scenes and fixed some apparent inconsistencies in Runciman’s account. That Graham had lived in Turkey was also very helpful.

Some may question whether a woman like Elisabeth could have fought as a knight. I was not able to find evidence of women who fought thus in the Crusades, but knowing about Joan of Arc, Boudica and Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, so I feel justified in portraying her as such. Her lesbianism is pure speculation.

One of the mysteries that came out of the Crusade of 1101 was what happened to Ida, Margravine of Austria, who disappeared and was never found again. The only theory extant, that she was captured and became the mother of a great Saracen leader, is easily dismissed as the man was already born when she arrived in Byzantium. This mystery provided me the opportunity as an author to suggest what may have happened to her and make it part of the story and my protagonist’s journey.

I firmly believe that as an author of historical fiction I have a responsibility to make the setting, characters and events as authentic as possible, but I also believe that nothing can substitute for good storytelling. Fiction and history texts are not the same. It is the function and beauty of historical fiction to bring the reader into a historical context in such a way that he or she can experience it as close to first hand as possible. I therefore feel free to insert myself, my ability to speculate and extrapolate, making, as far as I see it something even more authentic than a straight retelling of historical record. The latter cannot even come close to telling the true story, if only because the historian focuses on primarily the people and places at the core of the events. A historical novelist can move the focus off these and onto the rest of the world and suggest how people at the time may have seen, reacted to and drawn their own conclusions.

Sunday, 5 June 2011

Beyond the Marquee: Toward a Common History

This article of mine was originally published in the February 2011 issue of Historical Novels Review.

Come and visit our panel "Are Marquee Names Really Necessary" with star authors Margaret George, C.W. Gortner, Susanne Dunlap, and Vanitha Sankaran at the 2011 Historical Novel Society North American Conference in San Diego, on Saturday, June 18.

Recorded history is wrong. It’s wrong because the voiceless have no voice in it.

These are the words of the late, great Mary Lee Settle, author of the classic Beulah Land Quintet, published in the 1950’s when both academic history and most historical fiction were narrowly focused on the elite. So many people have been written out of history: not only the vast majority of women, but also people of the peasant and labouring classes, and most people of non-European ancestry. In Settle’s day, a more inclusive history seemed a far off dream.

“There’s a revolution going on out there!”

Sarah Dunant, acclaimed author of The Birth of Venus and In the Company of the Courtesan, remembers this time. Speaking at the Bluecoat School in Liverpool in May 2010, Dunant described how she first fell in love with historical fiction when she was a twelve-year-old in postwar Britain, which she remembers as “a grey, colourless, bleak place” where nobody wanted to talk about the war. On the brink of adolescence, she found a wonderful escape in Jean Plaidy’s novels of the crowned heads of Europe. These books not only opened up another world that was colourful and glamorous but they inspired Dunant’s lifelong love affair with history. She went on to study history at Cambridge. “The history I learned,” she recalls, “was the history of great battles, great empires, great men.”

But what inspired Dunant to become a historical novelist were the sweeping developments in academic history that occurred after she left Cambridge in 1972. This new history embraced people who did not belong to the elite. She cites Joan Kelly-Gadol’s 1977 essay, “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” as one of the turning points in the development of how we look at history.

Sarah Dunant is not only a champion of a more inclusive, non-elitist historical fiction—she also became an international bestseller by writing about people on the margins of history. Her most recent novel, Sacred Hearts, explores the secret world of Benedictine nuns in 1570 Ferrara, Italy—a cloistered “republic of women” where each choir sister had a voice and a vote in the daily chapter house meeting.

“Modern historians,” Dunant explains, “know that there is a multiplicity of history—there is more than one history, one fact. The history I’m using has been hard won over the past twenty to thirty years.” And this history allowed her to write novels about a past that simply wasn’t regarded as history even thirty years ago. For Sacred Hearts, she has drawn on two generations of young historians who examined court records of nuns who got into trouble.

Similarly, I could not have written my most recent novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill, which is based on the true story of the Pendle Witches of 1612, without the drawing on groundbreaking social histories, such as Keith Thomas’s Religion and the Decline of Magic; landmark works on Reformation Studies, like Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars and Ronald Hutton’s The Rise and Fall of Merry England; as well as recent studies on historical cunning folk.

Is the tide, then, changing? Will this new history open the door to a Renaissance in the historical novel? Will more and more authors draw on this wider window into ordinary people’s lives instead of rehashing the same old tired tales of Tudor royalty? Dunant believes that historical novelists possess every potential to be on the cutting edge of bringing this new history in an accessible form to a modern audience. “Wake up, there’s a revolution going on out there in historical fiction!” Dunant told Lucinda Byatt in their May 2010 Solander interview.

Marquee names only, please

Although the world of academic history has moved on light years since the 1950s, historical fiction often appears to be stuck in a rut. In these recessionary times, an increasingly conservative publishing market urges new and established authors alike to play it safe by writing about famous historical figures, such as Tudor royalty, instead of drawing on a social history of the less privileged.

Speaking at the 2007 Historical Novel Society Conference in Albany, New York, agent Irene Goodman stressed the importance of “marquee names” in finding an audience for one’s historical fiction. In the May 2010 issue of Solander, Goodman cited author Leslie Carroll’s leap from midlist obscurity to major success with the sale of her trilogy of novels about Marie Antoinette. Goodman is not alone in stressing the importance of marquee names.

“The trend simply cannot be denied,” Bethany Latham, Managing Editor of Historical Novels Review, observes. “For better or worse, publishers seem to prefer marquee names right now. They’re the path of least resistance—easier to market since, in the mind of many publishers, celebrity protagonist equals ready-made audience. There’s even a tendency for successful authors who began differently to evolve into something that better fits the prevailing mold—witness Philippa Gregory, who started out with the Wideacre Trilogy but has ended up with the familiar big-name Tudors and Plantagenets, and will be sticking with them for the foreseeable future.”

Popular fascination with historical It Girls like Anne Boleyn helped launch the incredible resurgence in historical fiction within the past decade, most notably through Gregory’s blockbuster, The Other Boleyn Girl. Literary agent Marcy Posner, speaking at the 2010 Historical Novel Society Conference in Manchester, UK, pointed out how Gregory’s glittering evocation of the Tudor Court inspired a large group of female readers to make the leap from historical romance to mainstream historicals. It seems only natural for agents and editors to look for work that contains the same kind of hook that proved so successful for Gregory.

“My experience was that when I sent some of my work to an agent,” says Elizabeth Ashworth, author of The de Lacy Inheritance, “she thought it was an engaging story and she liked my style of writing but she didn’t think she could sell my work to a publisher because it wasn’t about a well known king or queen. When I mentioned that I was working on another novel set in the reign of Edward III, she replied that if I wrote about Edward and Piers Gaveston, she might be interested. But that story has been written many times before and it was another story I wanted to tell – one about Lady Mabel Bradshaw who lived at that time but is relatively unknown.”

“The marquee name, especially female, has become almost a requirement in historical fiction,” says C.W. Gortner, author of The Confessions of Catherine de Medici. “My novel, The Last Queen, languished unpublished for years, with several of my rejection letters pointing out that Juana [of Spain] was not a ‘known personage’. I persisted and eventually found success, but how many other writers give up?”

The insistence on marquee names was why author Jeri Westerson says she switched to writing historical mysteries. “I preferred to write about the everyman in an historical setting, but year after year, I was told by editors that my medieval stories needed to be about royalty or other noble personages. The kind of historical I wanted to write translated much better to the mystery genre. So now I write medieval mysteries (after some eleven years of peddling historical manuscripts and not selling them).” Her fourth Crispin Guest Medieval Noir, Troubled Bones, will be released in Fall 2011. However, other historical mystery writers embrace the marquee name trend by choosing a well known figure such as Elizabeth I or Oscar Wilde as their sleuth.

Susanne Dunlap, author of Liszt’s Kiss and The Musician’s Daughter, adds that in Young Adult Fiction, the pressure is to write “something that fits into the high school curriculum,” which may well involve including famous personalities.

The bias can sometimes be found among HNS members themselves. Historical Novels Review Book Review Editor Sarah Johnson has noticed that reviewers tend to clamour for books about big names while novels about less familiar characters and settings can be harder to place.

Not even the most elite literary circles are immune to this trend. Hilary Mantel’s Booker Award winning masterpiece Wolf Hall is set in Henry VIII’s court.

A lack of diversity in the genre?

So does this push to write about marquee names help or hinder historical fiction?

“This is the backwash of celebrity culture,” Dunant states, “and our greed for sensation and scandal. People read about Anne Boleyn when they tire of reading about Paris Hilton. We’ve gone back to kings and queens, a celebrity history, because we’ve squeezed Paris Hilton dry.”

Must we all write like latter day Jean Plaidys and Georgette Heyers in order to meet our publishers’ sales expectations? Bethany Latham laments to think that in today’s climate, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, the bestselling historical novel of all time, might not be published because Scarlet O’Hara is a nobody.

Alison Weir, speaking at the 2010 HNS Conference in Manchester, presents a different viewpoint, arguing that her novels on figures such as Elizabeth I and Eleanor of Aquitaine are a legitimate way of reclaiming women’s history, even though they are focused on elite women. As Keynote Speaker at the conference, Weir explained how she pitched a nonfiction biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine some years ago only to be told that not enough material existed on her to make her a worthy subject.

“I think many readers gravitate toward the familiar,” Sarah Johnson observes, “and historical fiction readers in particular often choose novels that help them gain insight into a real-life character’s mindset or behavior. In that sense, I can see why marquee names are so popular, and why authors are being encouraged to choose them as subjects. It’s an automatic ‘hook.’”

Johnson added that the industry’s insistence on marquee names has the unfortunate drawback of creating a “lack of diversity of the genre.”

“The push for ‘big names’ is primarily about name recognition,” state N. Gemini Sasson, author of The Crown in the Heather. “The casual historical fiction reader scanning the shelves at the local Target store is more likely to linger over a name she recognizes, pick up the book and buy it, than an unknown. I do wonder though when a saturation point for some of these historical persons will be reached and the scales tip the other way.”

“If I see another book on the Tudors, I’ll scream!”

Which begs the question: are historical fiction readers beginning to reach their saturation point with historical celebrities? Eager to ape Philippa Gregory’s success, many authors have tried to follow her formula, with mixed results. How many more novels about Tudor royalty can the public bear?

“Frankly, if I see another book on the Tudors, I’ll scream,” HNS member Monica Spence admits.

“When I’m book-buying, the Not Anne Boleyn Again Syndrome periodically strikes,” Bethany Latham confesses.

Anne Gilbert says that she tends to shy away from fictional biographies. “No matter how well-written they may be,” says Gilbert, “they tend to concentrate on pretty much the same well-known historical people.”

“There are only so many ‘ultra famous’ women we can write about, whom publishers find commercial enough,” C.W. Gortner observes. “Take, for example, Eleanor of Aquitaine; as fascinating as she is, how much more can be said about her without it becoming repetitious or whimsical in novelized form?”

A 2009 market research poll conducted by blogger Julianne Douglas on Writing the Renaissance indicates that only 11% of the people she surveyed buy historical fiction based on the appeal of marquee names alone. Readers want so much more out of their fiction: fascinating characters and storylines, arresting and richly realised settings.

Finding an audience

Following the Publisher's Weekly listings of best-selling historical fiction on her blog, Reading the Past, Sarah Johnson mentions Edward Rutherfurd, Lisa See, and Sandra Dallas as just a few commercially successful authors who have bucked the big name trend. Their novels reached a wide audience because they have additional hooks that attract readers, Johnson points out, such as strong book club potential, and they also appeal to many readers outside the core historical fiction audience. Bethany Latham praises Maggie O’Farrell as a successful author with a fresh, original voice, who is utterly unaffected by the celebrity trend, not to mention Kenneth Follett, whose blockbuster Fall of Giants saga depicts ordinary people against extraordinary historical backdrops.

However, HNS member Matt Phillips, who is writing a novel based on his ancestors on the Pennsylvania frontier, still feels that not enough historical fiction based on the lives of “real people” is reaching the reading public. “There are so many stories that can shed light on how the ‘average person’ lived, or might have lived, while also entertaining the reader, engaging his or her imagination and emotions authentically with the thrills and fears and hopes and challenges of living in another time. Yet relatively few such stories find their way to the shelves of our bookstores because publishers continue to emphasize the marquee names.”

What happens when new or midlist authors embrace the lives of people on the margins of history? Gabriella West’s novel Time of Grace (Wolfhound Press, 2002) is a daring work—a woman-centered look at a very male period in history, Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising, and also a romance between two young women. “It was successfully published but I’m not sure it was published successfully,” West says. “It never really found its audience.”

Joyce Elson Moore’s has had a happier experience with her new novel, The Tapestry Shop, based on the life of Adam de la Halle, an obscure 13th-century musician. “His secular plays and music are still being performed,” Moore explains, “and he was one of the last and greatest of the trouveres (like troubadours in southern France). He penned the first version of the Robin Hood legend, and I felt like his story had to be told. The book is getting a lot of attention, and I think one reason is that it is different.”

Elizabeth Ashworth reports good sales on her own first novel, The de Lacy Inheritance. “I was lucky that my publisher Myrmidon Books was willing to take my novel, although the main character is a leper. It’s selling well and I think that proves the publishers wrong who maintain that readers only want to read about kings and queens.”

“Just give us variety.”

“To be honest, I’m not sure I’d be able to work with the constraints of a documented marquee name,” says Vanitha Sankaran, whose debut novel Watermark explores the life of a woman papermaker in late medieval France. “As a writer, I like the freedom of being able to create my own characters and stories while staying accurate to the era. As a reader, however, I’m interested in reading about all different t ypes of people, from the poor man trying to feed his pregnant wife to the merchant seeing his profits swallowed up by war. I wish publishers would take more risks across the whole genre and not focus on any time, place, or biographical person, but just give us variety.”

Sarah Johnson agrees that “those who stick narrowly to celebrity characters are missing out on some wonderful stories! In particular, the Editors’ Choice selections in Historical Novels Review demonstrate that historical fiction readers’ most highly recommended books don’t follow trends or fit into neat categories.”

N. Gemini Sasson sums it up beautifully: “There are less well known historical figures that have stories worth telling, every bit as compelling and dramatic as those whose stories have been told a hundred ways already. Sharing their lives would do nothing but enrich our view of the past.”

Perhaps we are indeed ready for a revolution in historical fiction.

“Time to Change the Marquee” by Julianne Douglas

“Bestselling Historical Novels of 2009” by Sarah Johnson

Labels:

historical fiction,

social history,

women's history

Tuesday, 26 October 2010

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change--Germany: 1560 - 1660

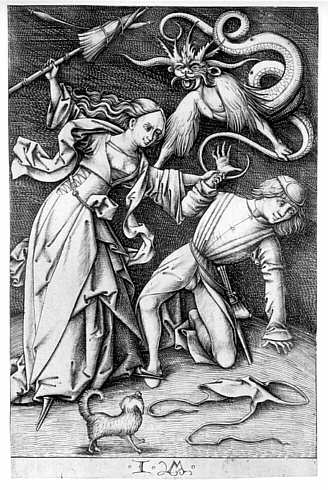

"The Evil Wife" by Israhel van Meckenem, 1440/1445-1503

A woman, encouraged by a demon, beats her husband with her distaff.

PART TWO

By the latter half of the 15th century, the feudal agrarian economy was beginning to crumble, while the capitalist market economy was growing more and more powerful, as did economic competition between men and women. Men active in the market economy tried to further their interests by simultaneously excluding women from many professions and trying to marginalize the domestic economy by claiming that home-produced goods were inferior to shop-produced goods. The guilds also began excluding women. Feeling their livelihood threatened by the competition with wealthy burghers, who set up their own industries and arranged for peasants to manufacture goods for them, male guild members struggled to initiate restrictions for women in the guilds. In 1494 in Cologne, for example, women were driven out of the harness-making guild for the first time. (Rauer 108).

In addition, traditionally "female" professions such as medicine were being taken over by men; male doctors had grown popular among the wealthy classes and were now also making inroads on medical care for the lower classes, and even encroaching on the very traditionally feminine occupation of midwifery (Ehrenreich and English 15-16--please note that the scholarship of this particular text has been called into question). Now we see the beginning of the sexual division of labor: women were beginning to be pushed into the ever-shrinking domestic economy, while men attempted to make the market economy their exclusive domain. This trend not only effected women on a purely economic level, but it also had a profound effect on women's social and sexual status. "The contraction and redefinition of women's productive and domestic roles was consistent with changes in the ideology of sexuality" (Merchant 150).

The Renaissance also ushered in a new ideal of bourgeois womanhood. The domestic sphere of the housewife and mother was idealized by Protestant intellectuals such as Martin Luther. "Gott hat Mann und Frau geschaffen, das Weib zum Mehren mit Kinder tragen; den Mann zum Naehren und Wehren," the Father of the Reformation wrote, advocating strict gender roles. "Im weltlichen politischen Regiment und Handeln antugen sie [Frauen] nichts, dazu sind Maenner geschaffen und geordnet von Gott, nicht die Weiber" (Rauer 112-113). (God created man and woman so that the woman would bear children and that the man would provide and defend. In worldly politics and trade, women should have no part--God created and ordained men for this, not women.) It must, however, be pointed out that Luther's own wife, the ex-nun Katharina von Bora was a very strong woman, beloved by her husband, who addressed her as "Herrin," or "my boss." She took charge of their household finances, farmed, raised and slaughtered livestock, and brewed vast quantities of beer to support Luther and his theology students and keep their household fed. She was the sole woman to take part in Luther's otherwise exclusively male "table talk" discussions.

Despite the positive recognition of woman as wife and mother that took place in the early Reformation, the misogynist ideology of the Catholic Church, such as Thomas Aquinas's contention that women are by nature morally weaker than men, remained in both Catholic and Protestant Churches. Also, Renaissance humanism pushed upper class women into the narrow role of being well-educated but submissive helpmates to their scholarly husbands. In 1499, Konrad Reutinger extolled his wife as the perfect Renaissance woman:

habe ich als Gattin ein Maedchen heimgefuehrt . . . schamhaft, bescheiden, schoen, etwas erfahren in den lateinischen Wissenschaften, die nie von ihren Hausgenossen streit- order schmaehsuechtig gesehen worden ist . . . . Daher weiss ich dem besten und groessten Gott jetzt und in Zukunft Dank, der meinem Studium eine Gefaehrtin und Anhaengerin gegeben hat, die mir aufs innigste vertraut ist. (Ibid 133)

(I've taken a girl home to be my wife [who is] modest, docile, beautiful, with some knowledge of Latin that those in her household have never come to view as overly ambitious or aggressive . . . . For this I thank the best and greatest God now and always, that he has given me for my studies a companion and follower in whom I trust absolutely.)

The Renaissance also saw the birth of a brand new bourgeois motherhood ideal. In the Middle Ages, mothers were expected to take care of their young children, but the mother-child bond was not as glorified to an almost sacred institution and be-all and end-all of a woman's existence as it would become in later centuries. Also, childhood, as we now view it, did not exist then; children were treated as small adults. Children of the lower classes who survived infant hunger and childhood diseases were sent away from their parents as soon as they were old enough to find work as servants in the wealthier estates (Hoher 20).

In the second half of the 15th century, the Catholic Church was losing its authority, under threat by serious challenges and dissent that would soon take the shape of the Reformation. During this divisive time, the Catholic Church expressed a new kind of religious aggression in enforcing morality and a new fascination with the devil. The hedonism that had reigned in medieval plebeian culture was no longer to be benignly overlooked. Wifely obedience in marriage began to be emphasized more and more. During this period, a new genre of literature originated: the Devil Book, which concentrated on explaining how certain activities, such as dancing and drinking, were sinful. The general effect of these publications was to imply that the devil was everywhere (Midelfort 69). The Catholic Church's attitude towards witchcraft also changed quite significantly--the ancient code saying it was sinful to believe in witches was reversed; now Church officials declared it sinful not to believe in them. They argued that a new sect had developed, which even the Fathers of the Church had been unable to foresee (Chamberlin 137). In 1484, Pope Innocent and two German Dominican friars, Kramer and Sprenger, issued a bull against witchcraft in response to rumors of widespread witch activity in Germany. This bull granted the use of inquisitorial techniques in witch hunting. Although the late 15th century was noted for religious intolerance, it was also characterized by a "new carelessness in law" (Ibid 69). The use of torture was revived with the re-establishment of Roman Law. This resulted in a considerable escalation in witch persecutions: "Torture allowed accusations to proliferate to epidemic proportions, because once a witch confessed under torture, she would be tortured again to divulge the names of her neighbors seen at the Sabbat" (Ruether 102). In 1486, Kramer and Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum was published. This highly misogynistic witch-hunting manual established the belief that women are by nature more prone to witchcraft than men: "Femina comes from Fe [faith] and Minus, since she is ever weaker to hold the faith . . . . Therefore, a wicked woman is by her nature quicker to waver in her faith, and consequently quicker to abjure the faith, which is the root of witchcraft" (Malleus 44). The authors of the book were also obsessed with the idea that the unquenchable carnal lust of women drove them to the devil: "All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which in women is insatiable . . . . Wherefore for the sake of fulfilling their lusts they consort with devils . . . it is sufficiently clear that it is no matter for wonder that there are more women than men infected with the heresy of witchcraft (Ibid 43).

As we have seen, women were beginning to be perceived as a threat to the new economic and religious developments. One cannot imagine that they were at all cooperative with the new infringements on the relative economic and sexual freedom they had enjoyed in the past. They would not submit easily to these changes--they would resist--and their resistance would make them a threat to the interests of the new order. In the arts and media of this period, women were constantly portrayed as domineering, threatening, lustful, violent, and powerful: a force that must be quelled. Village festivals of this period often had floats featuring wives beating their husbands, hurling refuse and rocks at them, and verbally abusing them. Numerous art works of this era, especially the works of Hans Baldung Grien and Albrecht Duerer, depicted the supposed disorder wrought by lusty women. Popular illustrations portrayed women beating their husbands with distaffs. Spinning was one of the occupations with which a woman could still make a decent living. The distaff symbolized her earning power and economic independence from her husband. These male artists interpreted woman's breadwinning power as something threatening, something she abused: her pride of being able to earn undermined her husband's authority. These women were not conforming to the new mold of wifely obedience that Church officials were stressing more and more. Thus, not only were women a threat to their husband's authority, they were also a threat to society in general.

One 1521 engraving by Urs Graf (unfortunately I could not find a jpeg of it to post here) depicts two young women savagely beating a monk who has probably molested them. In the Renaissance, women were portrayed as capable of violence, revenge, and self-defense. Urs Graf's women respect neither male nor religious authority; they assume the right to punish any man who tries to molest them. Hans Baldung Grien's engraving, "Aristotle and Phyllis," below, shows the legendary Phyllis literally making an ass of Aristotle. In all these pictures, women are portrayed as violent, crafty, and insubordinate. Their male victims are portrayed as pathetic, weak-willed fools for allowing themselves to be dominated by women. The message that I read into these art works is that women are trying to hold the upper hand. They will not allow themselves to be forced into the new "proper" feminine sphere. In order for women to be put in their place, men must assert their dominance. Thus, these male artists perceive women as a powerful, chaotic force that needed to be violently subdued. This violence against women would not be long in coming.

"Hercules among the maids of Queen Omphale" by Lucus Cranach the Elder: these women are emasculating the mighty Hercules by dressing him in a women's coif and pressing a distaff into his hand.

"Aristotle and Phyllis" by Hans Baldung Grien, 1513.

Aristotle who proclaimed that the male is superior to the female is shown subjected to Phyllis who literally makes an ass of him.

Labels:

art,

reformation,

renaissance,

witchcraft,

women's history

Monday, 25 October 2010

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change

I recently revisited my Senior Paper, written in 1988 at the University of Minnesota. Although some of my sources are *very* dated, most of the actual historical information seems to have stood up to the test of time and, though my focus in this paper was Germany, much of this material seems prescient for what I would later write in DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL.

Especially important in my research was the realization that women in the Middle Ages actually had more economic power and independence than they did in the Renaissance and Early Modern Period. I highly recommend Joan Kelly's iconic essay, "Did Women Have a Renaissance?", reprinted in Women, History & Theory: the Essays of Joan Kelly, University of Chicago Press, 1984.

So as an All Hallows offering, I thought I would repost my paper here, in digestible chapters. Keep in mind that I was a college senior when I wrote it, not a PhD candidate, and that I majored in German, so some of my sources are German language. Please note that in the twenty years after I wrote this papar, a lot more scholarship has been done on historical witchcraft studies, and if you are interested in reading more, please refer to the more recent books. I'll try to post a more updated reading list later.

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change: Germany: 1560 - 1660

Part One

The 16th and 17th centuries were one of the bleakest periods for European women. From roughly 1560 to 1660, the witch hysteria claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people, around 75% of whom were women, many of them older women of the lower classes (Ruether 111). One of the worst areas of persecution at this time was Southwest Germany. The question I shall try to answer in this essay is why the witch persecutions often seemed to focus on poor, elderly women. Were these women viewed as a threat to the social order to be violently subdued? What is the historical context for this? How do the persecutions relate to the rise of capitalism, the decline of the domestic economy, the male takeover of tradtionally female professions, the tightening moral and religious strictures, and the peasant rebellions? I will begin to try to answer these questions by tracing the development of the witch burnings over history and the status of women in these different historical periods: from the Middle Ages, when there were very few witch persecutions and women enjoyed relative economic and sexual freedom; to the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, when men and women began to compete in the market economy and women were beginning to be perceived as a threat, and the number of witch persecutions significantly increased; to the last half of the sixteenth and the first half of the seventeenth century, when the mass persecutions took place and women were forced into a far more restricted sphere, ecnomonically and morally, than they had experienced during the medieval period.

Very little witch persecution took place in the medieval period. Although, by the early Middle Ages, most of Europe had been at least nominally Christianized, many old pagan folk ways survived. Such tradtional seasonal festivities such as Walpurgis (May Eve), Fastnacht (the wild festivities that preceded the solemn fast of Lent), harvest homes, and the like often featured much feasting, drinking, and sexual licentiousness. Church officials did not necessarily condone these activities, but the Church, at this point in history, was content to erect a superstructure of Christianity over this rural plebian culture (Ibid 93). To a great extent, the Church looked the other way in cases of lapses in sexual morality, and men and women often did as they pleased. Thus, the customs and behaviors which would later be connected with witchcraft were tolerated and often ignored by the early medieval Church (Ibid 99).

During the Middle Ages, beliefs about what constituted magic and witchcraft slowly evolved. During the early medieval period, the Church viewed witchcraft and magic merely as pagan superstition. In the 8th century, for example, Boniface, the English apostle of Germany, declared that believing in witches was unchristian. In the same century, Emperor Charlesmagne denounced witch burnings as foul remnants of paganism and initiated the death penalty in newly converted Saxony for anyone who committed this sinful act (Trevor-Roper 92). Having firmly established witch persecutions as pagan superstition, the Church maintained a healthy skepticism in regard to the idea of witchcraft (Midelfort 14). In fact, up until the late 15th century, the Church declared it a sin to even believe in witches (Chamberlin 137). Thus, the medieval period until this point was far more "enlightened" in regard to the subject of witchcraft than the next few generations would be. As we shall see, the witch craze was a phenomenon of the Renaissance, Reformation, and early modern period.

The econominc structure of the medieval period until about 1450 was based on the feudal agrarian system, peasant control of production, and a dominant domestic economy. The peasants worked the lord's land and this guaranteed them their livelihood: from the harvest, they took what they needed for survival, while the lord took the surplus. Feudalism necessitated cooperation and interdependence on the part of peasants. For example, the introduction of the heavy plow during Carolingian times made it necessary for the serfs to work together to get a plow and a team of horses or oxen for it. They also decided communally what to plant, where they would plant, which fields to leave fallow, how crops should be rotated, and how the harvest should be divided. Although the landlord benefitted the most from this system, the peasants made the major decisions and controlled production. This subsistence ecnonomy was a domestic economy: almost all the goods necessary for survival were produced by peasant family units in the household (Ketsch 83).

The domestic agrarian economy and culture allowed women relative economic freedom. Work among the lower classes did not have any rigid gender division at the time. Male and female peasants worked alongside each other in the fields. Male and female servants of the same class often did identical work. The only female-specific work was housework, child-rearing, midwifery, and prostitution. In addition, herbal medicine and the crafts of brewing, spinning, and weaving were thought to be more "female" than "male" professions. Among the lower classes, however there was no specifically "male" work. Rigidly defined gender spheres existed only among the feudal nobility: women were responsible for reproduction and household management, while men took over martial responsibilities (Hoher 14).

No rigid gender division was evident in the market economy at this time, however. Men and women participated on a relatively equal basis in the flourishing craft guilds in the imperial cities. In the 13th through 15th centuries, women were admitted to all guilds. Although, in the early Middle Ages, there had been restrictions regarding independent female masters--that is women masters not married or related to male masters--this situation improved in the 13th century. Women began founding their own guilds and taking part on a more equal basis in the mixed guilds (Hoher 15). A document from a yarn making guild in Cologne in the last 14th century, for example, gives detailed regulations specifically regarding female apprentices and female masters: "Welches Maedchen das Garnhandwerk in Koeln lernen will, das soll vier Jahre dienen and nicht weniger . . . . Und sie soll in den vier Jahren nicht mehr als zwei Frauen dienen." (If a girl wants to learn the yarn making craft in Cologne, she must apprentice at least four years . . . . and in these four years, she should serve no more than two women.) This document also outlines the special provisions made for husbands of deceased female masters. Another guild document gives evidence for both male and female masters working in a bath house: "Kein Meister and keine Meisterin soll eines anderen Badegaeste zu sich bitten, bei einer Strafe von halben Pfund." (Rauer 104). (No male master or female master should solicit someone else's bath guest client, on pain of a fine of half a pound.) Women were also quite acrive in selling and trading, especially in materials commonly used in both medicine and folk magic. (Hoher 16).

From the 12th to the mid 15th century, Europe was underpopulated and the workforce needed women. At this time, there was little economic competition between the sexes and the split between the domestic and the market economy had not yet been fully established (Ketsch 117). So, as we have seen, women were relatively economically independent during this period.

There were also viable alternatives to the domestic sphere of marriage and motherhood during the Middle Ages. Convents attracted noblewomen who wished to free themselves from a life of child-rearing and to devote themselves to religion and learning. Beguinages--urban and secular all female communes--motivated women of the lower classes to leave the country for the city. Some women even became vagabond musicians and mercenary soldiers. There were also a few female hermits: single women who lived on the outskirts of towns and forests, and often practiced herbal medicine. These solitary women would later become victims of the witch hysteria in the Renaissance (Boulding 210-211).

The feudal agrarian system was not to last forever. The landlords' tendency to extract from unfree peasants any handy income above subsistence meant that these peansant were unable to give back what they took from the land. Thus, a combination of bad farming techniques leading to soil depletion, steady population growth, and the overtaxation of peasants by land owners all contributed to the gradual breakdown of the feudal agrarian economy and ecosystem (Marchant 47). As the feudal agrarian and domestic economy wanted, the capitalist market economy grew stronger. This had a profound effect on the socio-economic status of women.

During the years 1450 to 1550, very dramatic economic, social, and religious changes took place that would threaten the status and freedom that medieval women had enjoyed. Up until 1450, both sexes were needed in the economy, but afterwards, competition began to take place between the sexes in the market economy. It is during this period that the sexual division of labor, and the separation between the market and the domestic economy began to develop. As men struggled to gain supremacy in the market economy and to push women, their competitors, out of the guilds and into the domestic economy, which was becoming more and more marginalized, women resisted. Women were beginning to be viewed by men as a threat to the order of society. At the same time, a tightening in the moral and religious strictures in both the Catholic and the newly developing Protestant Churches began. The sexual licentiousness, dancing, and drinking that had been commonplace in the medieval period was increasingly frowned upon. Religious authorities grew more obsessed with morality, and the concepts of the devil and witchcraft than they had been before. During this period, the number of witch persecutions rose significantly. The events that took place between 1450 and 1550, thus, were decisive in laying down the foundation for the later witch crazes of 1560 to 1660.

Boulding, Elise. "Familial Constraints on Women's Working Roles," Women and the Politics of Culture, Zak & Moots, eds., Longman Inc., New York, 1983.

Chamberlin, E.R., Everyday Life in Renaissance Times, Pedigree, London, 1965.

Hoher, Friederike. "Hexe, Maria und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichkeit im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol. III), Kuhn & Rusen, eds., Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Ketsch, Peter. Frauen im Mittelalter (Vol. I) Kuhn (ed.), Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Midelfort, Erik, H. C. Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations, Stanford, 1972.

Merchant, Carolyn. The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Rauer, Brigitte. "Hexenwahn--Frauenverfolgung zur Beginn der Neuzeit," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol. II), Kuhn & Rusen, (eds.), Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1982.

Reuther, Rosemary. New Woman/New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation, Seabury Press, New York, 1975.

Trevor-Roper, H.R. The European Witch-Craze of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Harper & Row, New York, 1969.

Labels:

medieval period,

renaissance,

witchcraft,

women's history

Friday, 22 October 2010

Writing Women Back into History

This illustration, from Wikipedia Media Commons, depicts medieval women hunting.

This article of mine was originally published in the May 2008 issue of Solander Magazine, published by the Historical Novel Society.

We have been lost to each other for so long. My name means nothing to you. My memory is dust.

This is not your fault or mine. The chain connecting mother to daughter was broken and the word passed into the keeping of men, who had no way of knowing. That is why I became a footnote, my story a brief detour between the well-known history of my father and the celebrated chronicle of my brother.

Anita Diamant, The Red Tent

To a large extent, women have been written out of history. Their lives and deeds have become lost to us. To uncover the buried histories of women, we historical novelists must act as detectives, studying the sparse clues that have been handed down to us. To create engaging and nuanced portraits of women in history, we must learn to read between the lines and fill in the blanks.

At its best, historical fiction can indeed play a crucial role in writing women back into history and challenging our misperceptions about women in the past. In her stunning novel The Red Tent, Anita Diamant turns our image of women in the Old Testament on its head by allowing the Biblical Dinah to tell her own story in her own voice. Donna Cross’s novel Pope Joan explores the tantalizing possibility that a 9th century woman might have once sat on the papal throne. In The Thrall’s Tale, Judith Lindbergh paints an unforgettable portrait of Thorbjorg, the 10th century Norse seidkona, or seeress, straight off the pages of the Saga of Erik the Red. Paul Anderson’s 1376 page epic Hunger’s Brides illuminates the life of Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, a 17th century Mexican nun who became the greatest New World poet of her age. Sor Juana fans will also want to read Alicia Gaspar de Alba’s novel Sor Juana’s Second Dream.

While many authors have focused on documented historical figures, others have embraced the ellipses in history as an invitation to speculate on women’s secret lives and untold stories. “Where history and biography are about the public world, fiction is about the private world,” says Jude Morgan, author of Passion and Indiscretion. “And that [private world] was perforce the women’s world, too: the private, often including the hidden and the unspoken. That’s where historical fiction can be revealing.” In her novels Tipping the Velvet, Affinity and Fingersmith, Sarah Waters imagines the smoldering passions that might have passed between women behind the façade of prim Victorian decorum. Jean Rhys, in her masterpiece Wide Sargasso Sea, resurrects the silenced Mrs. Rochester, the madwoman in the attic in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, and brings her to life as a tragically misunderstood Creole heiress. Louise Erdrich has written an entire body of work portraying the women (and men) of her mother’s line, the Anishinaabe Nation.

Not surprisingly, many of these novels that capture the hidden truths of women’s histories have been runaway bestsellers. Diamant’s Red Tent, first published in 1997 with no advertising budget, became a word of mouth blockbuster and went on to sell to 25 foreign markets, while Cross’s Pope Joan is now in its 18th printing and inspired a major motion picture starring German-born actress Franka Potente. Louise Erdrich’s National Book Critics Circle Award-winning first novel Love Medicine has never been out of print.

At the end of the day, it’s a question of knowing your market. Although it’s hard to pin-point precise figures, the majority of buyers and readers of historical fiction appear to be women and they seem to crave books that present compelling portraits of strong female protagonists.

Most interesting is the possibility that historical fiction’s rewriting of women’s history has wider repercussions in the world of nonfiction.

“Historical fiction has a way of bringing figures neglected (or subordinated) by the history books back into the foreground,” says Bethany Latham, Managing Editor of HNR. “Historical fiction can do this where history tomes fail because it is fiction –it’s not bound strictly by documented fact. For instance, an historical fiction author can write an engrossing novel centering around a ‘minor’ female courtier, where a truly enlightening biography of the woman is problematic due to the dearth of historical information about her (think Philippa Gregory's Boleyn Inheritance versus Julia Fox’s exceedingly speculative biography of Viscountess Rochford).

“Historical fiction treatments thrust historical female figures, whether they be aristocrats or serving maids, into the public eye,” Latham continues. “Nonfiction authors cannot help but be influenced by the rampant popularity of a particular historical period or person promulgated by historical fiction and the screen adaptations the novels spawn; it causes them to look for their own ‘angle’ – for what hasn’t been done, what’s been overlooked – in order to focus their research on it. . . . Historical fiction can grab [women] by the farthingale and drag them into the limelight, leading to greater interest in them, more research into their lives, and subsequently a greater understanding of the part women have played in history.”

jay Dixon, author of The Romance Fiction of Mills & Boon: 1909-1990s, speculates that historical novelists may have been pioneers in the women’s history movement. “Ever since the publication of Sheila Rowbotham’s Hidden from History in 1973, feminists have been trying to rescue women from their invisibility in male discourses of history,” says Dixon. “But prior to that, women authors, in their historical novels, fore-fronted women – the wealthy, the poor, the powerful and the downtrodden – from all periods and all locales. Using imagination alongside research, they told the stories that could have happened, and maybe did. And in doing so not only gave voices to the voiceless, but also changed our perception of the past.”

HNR Editor Sarah Johnson cites Anya Seton’s classic novel The Winthrop Woman, first published in 1958, which tells the story of 17th century Elizabeth Winthrop, wife of Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The novel reveals how she defied her husband and community in order to befriend Anne Hutchinson, the famous heretic who later went on to found the colony of Rhode Island.

Exploding myths

Unfortunately writers can run into problems when they present a view of historical women that challenges our common misperceptions. On the one hand, readers and critics are justifiably skeptical about novelists who present plucky historical heroines with attitudes that feel too contemporary and thus anachronistic to their time and place. On the other hand, if you sit down and do the research, you will discover that every epoch had its radical voices, movers and shakers, extraordinary women who rocked the establishment. Think of Sappho, Hypatia, Hildegard of Bingen, Elizabeth I of England, Aphra Benn, Anne Bonny the Pirate Queen, Emma Goldman, and Rosa Parks, to name a few. Too often readers and, unfortunately some reviewers, appear to have a distorted and uninformed view of women in history and seem too quick to label any strong heroine anachronistic, even if the author has backed up the fiction with considerable research. Too often we base our picture of women in the past on the lazy assumption that all women throughout all of history were completely downtrodden and disempowered.

In preparation for the Rewriting Women’s History panel at the 2007 HNS North American Conference in Albany, New York, I conducted an informal survey with members of the HNS email discussion list, asking what they thought were the most annoying historical clichés about women. Here are some of the responses:

Women’s lives were completely limited to the domestic sphere.

Before Betty Friedan came along, all women were housewives and mothers and nothing else.

Women in the Victorian era led lives of leisure. (In fact, very few did.)

Women in the past did not enjoy sex.

Dr. Irene Burgess, Provost and Dean of Eureka College, Illinois, reminds us that what we know – or think we know – about women in history is mediated and changes over time. “Representing historical women in twenty-first century fiction can be difficult,” Burgess points out, “because of the automatic lenses that a current audience places on the behavior of women from an older period. Because mores and language were so different, it’s frequently difficult for current-day readers to believe that women of the past had autonomy, capability, and choice.

“A lower class woman of the 14th century in England,” Burgess continues, “probably had greater degrees of freedom than an aristocratic woman of the 18th century in Italy. Although readers may perceive it as anachronistic to have a female weaver going to the tavern with some of her friends and telling her husband to take a hike if he protests, that probably did happen.”

Dr. Samantha Riches, Director of Studies for History and Archaeology at Lancaster University, UK, agrees that the reality of medieval women’s lives defy our popular conceptions. “The idea that women sat around creating tapestries and looking wistful is still quite widespread, largely due to Hollywood films perpetuating the same stereotyped ideas. Sources about women’s personal experiences are few and far between, but we do have a few gems like the Paston letters (accessible via the Internet Medieval Sourcebook), which can give us a real insight into the lives of late medieval women. In 1448 Margaret Paston wrote to her husband John with a shopping list including almonds, sugar and crossbows: he was away in London and she was aware that she would need to organize defense of their property in East Anglia against a neighbor with whom they were involved in a dispute.”

Although there are even fewer sources regarding the lives of common women, Riches believes that the visual evidence tends to indicate that women were employed in a wide range of occupations. Erika Uitz’s scholarly study Women in the Medieval Town reveals that women worked as merchants, money-lenders, brewers, and even miners. One of the book’s illustrations shows a detail of Hans Hesse’s early 16th century “Miners’ Altar” panel painting, which depicts a woman washing the heavy iron ore—a job that was even more backbreaking than mining.

The colorful lives of medieval women have inspired Paul Doherty’s most recent mystery series, centered on 14th century physician Mathilde of Westminster, who is based on a historical figure. “We tend to think of women’s rights developing over the centuries; this is simply not true,” Doherty said when I interviewed him in the May 2006 Historical Novels Review. “I think it was Dorothy Mary Stenton, the famous Anglo-Saxon historian, who pointed out that women had more rights in 1100 then they did in 1800!”

Indeed, the 1800s would appear a big stumbling block in our perceptions of the past. “The early 19th century marked the nadir of European women’s options and possibilities,” Bonnie S. Anderson and Judith P. Zinsser write in A History of Their Own, Volume 2. “The creation of ‘women’s movements’ in the 19th century was in part a response to this.”

The Victorian era in particular has made a lasting imprint on the modern psyche. Suzanne Adair, author of Paper Woman and panelist at the Albany conference, notes that too often people look at women in the past through the lens of Victorian culture and base their view of women in completely disparate epochs on this stilted stereotype of the tightly corseted, sexually repressed Angel of the Home. “We like to think of ourselves as much more progressive than earlier generations,” Irene Burgess adds, “but when it comes to issues such as sexuality and the body, we actually are more repressed – a product of our Victorian ancestry. One only has to think of the Wife of Bath or the poems of Sappho to realize that that is the case.”

But even 19th century women’s lives were more complex than many realize: the Industrial Revolution drove countless women and girls out of the kitchens and into factories and mills, inspiring the line in the popular early 19th century folksong, The Weaver and the Factory Maid:

Where are the girls? I will tell you plain:

The girls have gone to weave by steam,

And to find them you must rise at dawn,

And trudge to the mill in the early morn.

As astute historians will point out, women throughout history have always worked. One of the experiences that inspired my third novel, The Vanishing Point, set in Colonial America, was a visit to a tiny Philadelphia row house where two 18th century seamstresses once lived and plied their trade. I felt immediately drawn into their world. It was exciting for me to see the proof that even in this era, when nearly every factor of the dominant religion and economy herded women into marriage and domesticity, some women still succeeded in carving out independent, masterless lives, ruled by neither father nor husband.