Showing posts with label witchcraft. Show all posts

Showing posts with label witchcraft. Show all posts

Saturday, 25 February 2012

British Folk Magic & Familiar Spirits

In popular imagination, the figure of a witch is accompanied by her familiar, a black cat. Is there any historical authenticity behind this cliché?

Our ancestors in the 16th and 17th centuries believed that magic was real. Not only the poor and ignorant believed in witchcraft and the spirit world—rich and educated people believed in spellcraft just as strongly. Cunning folk were men and women who used charms and herbal cures to heal, foretell the future, and find the location of stolen property. What they did was illegal—sorcery was a hanging offence—but few were arrested. The need for the services they provided was too great. Doctors were so expensive that only the very rich could afford them and the “physick” of this era involved bleeding patients with lancets and using dangerous medicines such as mercury—your local village healer with her herbal charms was far less likely to kill you.

Those who used their magic for good were called cunning folk or charmers or blessers or wisemen and wisewomen. Those who were perceived by others as using their magic to curse and harm were called witches. But here it gets complicated. A cunning woman who performs a spell to discover the location of stolen goods would say that she is working for good. However, the person who claims to have been falsely accused of harbouring those stolen goods could turn around and accuse her of sorcery and slander. Ultimately the difference between cunning folk and witches lay in the eye of the beholder.

While witch-hunters were obsessed with extracting “evidence” of a pact between the accused witch and the devil, there’s little if any substantive proof of diabolical worship in Britain in this period. It seemed the black mass was a Continental European concept first popularised in Britain by King James I’ polemic, Daemonologie, a witch-hunter’s handbook and required reading for his magistrates.

In traditional British folk magic, it was not the devil, but the familiar spirit who took centre stage. The familiar was the cunning person’s otherworldly spirit helper who could shapeshift between human and animal form. Elizabeth Southerns, aka Old Demdike, was a cunning woman of long standing repute, arrested on witchcraft charges in the 1612 Pendle witch hunt in Lancashire, England. When interrogated by her magistrate, she made no attempt to conceal her craft. In fact she described in rich detail how her familiar spirit, Tibb, first appeared to her when she was walking past a quarry at twilight. Assuming the guise of a beautiful, golden-haired young man, his coat half black, half brown, he promised to teach her all she needed to know about the ways of magic. When not in human form, he could appear to her as a brown dog or a hare. Her partnership with Tibb would span decades.

Mother Demdike was so forthcoming about her familiar because without one, she, as a cunning woman, would be a fraud. In traditional English folk magic, it seemed that no cunning man or cunning woman could work magic without the aid of their familiar spirit—they needed this otherworldly ally to make things happen.

Black cats were not the most popular guise for a familiar to take. In fact, familiars were more likely to appear as dogs. In the Salem witch trials of 1692, two canines were put to death as suspected witch familiars.

But the familiar was just as likely to assume human form, generally the opposite gender of their human partner—cunning men usually had female spirits while cunning women usually had male spirits.

Was there a connection between the familiar spirits and the Fairy Faith, the lingering belief in fey folk and elves? Popular belief in fairies in the Early Modern period is well documented. In his 1677 book, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, Lancashire author John Webster mentions a local cunning man who claimed that his familiar spirit was none other than the Queen of Elfhame herself. In 1576, Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop, executed for witchcraft and sorcery at the Edinburgh Assizes, stated that her familiar spirit had been sent to her by the Queen of Elfhame. For more background on this subject, I highly recommend Emma Wilby’s scholarly study, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits, and Keith Thomas’s social history, Religion and the Decline of Magic.

Sunday, 15 January 2012

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change: Germany 1560-1660

PART FOUR, Last in a series

Read Part One, Part Two, and Part Three

.

The late 16th and early 17th century was an era of radical social, economic, and religious change. As women had much to lose, they had reason to rebel. And they remained a threat to the new social order. Art of this period often depicted women as insubordinate and wanton: beating their husbands, swilling wine, and lustfully dragging men to bed (Merchant 133). Reformer John Knox was of the opinion that if a woman was presumptuous enough to rise above a man, she must be "repressed and bridled" (Ibid 145). This was one of the most bitterly misogynistic eras ever known.

Political and religious leaders seemed terrified by their fear that witches had organized themselves into a secret female society, as described in Kramer and Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum and King James's Daemonologie, among other works.

During witch trials, the witchfinders obsessively tried to force the accused to describe what went on at the alleged sabbat and to name the other women she had seen there. Georg Pictorious, a physician and scholar at the University of Freiburg in Germany, believed that witch persecutions were the only way humanity might be saved from these evil women. He maintained that if all the witches "are not burned, the number of these furies swells up in such an immense sea that no one could live safe from their spells and charms" (Midelfort 59).

In the 1970s and 1980s, some feminist historians such as Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English drew on Margaret Murray's study from the 1920s, The Witch Cult of Western Europe, to try to prove that there was indeed a secret society of women who practiced magic as part of an organized pagan cult. (See Ehrenreich and English's Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers)

While these speculations are very interesting, scant evidence exists to support this theory and most of it is based on torture-induced confessions.

It is, however, safe to state that people during the period of the witch persecutions sincerely believed and feared the existence of a secret female society.

Witches were believed to be a threat to both Christianity and to the middle class as it struggled to gain social authority (Hoher 46). The anti-puritan, plebian culture of lower class women stood in the way of the new values of the emerging bourgeois society. The stereotype of an organization of women out of control of society, women who cursed their enemies and mocked Christianity with their bizarre orgies, is perhaps indicative of an actual grain of reality behind the public fears. Hoher suggests that the rapidly changing society in Early Modern times, the role of the individual in a world that seemed increasingly confusing and uncertain, led to a collective insecurity--a fear that society would regress into old feudal traditions and chaos.

This fear was taken out brutally on those who would not integrate into the new order. The continuing disorder of the rural plebian culture and the refusal to conform to the new system took shape in the paranoia of the witch craze. Women, who according to Thomas Aquinas, Kramer, Sprenger, and others, were by nature weak-willed and sensual, were feared as the chief representatives of this rebellion--the chaos of uncontrolled nature and sexuality that must be subdued. Thus, it was these disorderly, uncontrollable women who were the most feared and hated. For the new order to survive, these women must be brutally exterminated (Ibid 42).

In examining the chronology of the witch trials, we see that the first trials targeted mainly poor, elderly women. As time went on and rich people and men started being accused, the witch hunts were considered to have got out of hand and they lost popular support. By this time, however, the new capitalism and religious order had been firmly established and the persecutions were no longer necessary.

This chronology reveals clearly what interests were at stake. The earliest trials of the 1560s focused almost exclusively on poor, older women. In the early trials of Wiesensteig and Rothenburg, 95 to 100% of the accused fit this stereotype. As the witch hunts progressed and the accused were tortured to name other witches, more and more men and upper class people were implicated (Midelfort 179). In Ellwangen in 1615, "accusations and convictions of highly placed and undoubtedly honorable men must have shaken people into recognizing that something had gone wrong" (Ibid 105).

Slowly the caricature of the witch as an old peasant woman was breaking down, "leaving society with no protective stereotypes, no sure way of telling who might be, and who could not be, a witch" (Ibid 182). Witch hunting so thoroughly shook up normal bonds of social trust that the most respected members of the community were no longer immune. The trials began to draw more and more criticism. Finally in 1672, the council of Altdorf in Schwaben declared all accusations of witchcraft illegal (Ibid 82). By this time, the persecutions had accomplished their original goal--the subjugation of rebellious lower class women and firmly entrenching those who survived the witch hunts into a subordinate domestic role. By the late 17th century we have no more illustrations of threatening, insubordinate women asserting their power.

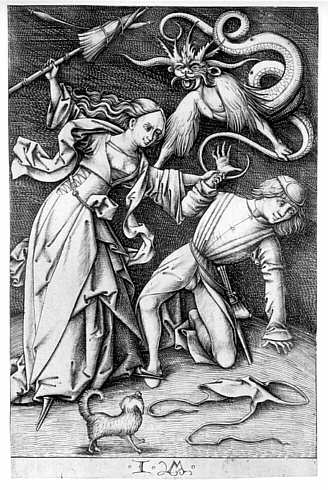

Why this emphasis on poor and elderly women and why the last half of the 16th and first half of the 17th century? This period was crucial for the development of modern capitalism, a stricter moral code, and the placement of women into a narrowly defined domestic sphere, with utter economic dependence on their father or husband. The women who would most likely resist, at least in the early years of the persecutions, would be the older peasant women who remembered and clung to the old ways of plebian agrarian culture, the domestic economy, and the social and economic power they enjoyed. Such women would not easily relinquish their economic independence, their right of subsistence, or their personal freedom. The young woman beating her husband with her distaff, the symbol of her economic independence, in the early 16th century, became the old woman accused of witchcraft fifty years on. Note that in the 16th century illustrations I have included here, the old witch is depicted not with a broomstick but with her distaff.

Post-menopausal women were unburdened by pregnancies and childbirth. This gave them more freedom, time, and energy to stir up trouble. The accused witches' descriptions of the sabbat sound like the witch hunters' perversion of the joys of plebian peasant culture--drinking, dancing, and uninhibited celebration and sexuality. The earthly pleasures of the older generation became the evil heresy of the next. Since the descriptions of the alleged sabbat were drawn by torture, we must be cautious when drawing conclusions, but it makes a certain amount of sense in this historical context.

The women who had been strong, economically independent, and pleasure-loving members of the previous generation would not throw away their old privileges easily, so they became the witches of the new generation, a threat to society that had to be violently subdued for the new order to become established.

Sources:

Hoher, Friederike, "Hexe, Maria und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichket im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol III) Kuhn/Rusen, (eds.). Padagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Merchant, Carolyn, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Midelfort, Erik, H.C., Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations Stanford, 1972.

Ruether, Rosemary, New Woman/New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation, Seabury Press, New York, 1975.

Note: This essay was my Senior Paper I wrote in 1988 while an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota. Some of the sources may seem dated, but I think most of the history still stands up.

In recent years some serious scholars have revisited Margaret Murray's contention that there was indeed a secret female society in Europe during the period of the witch persecutions. See Carlo Ginzburg's book Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath and Emma Wilby's brilliant new book The Visions of Isobel Gowdie.

This website provides an interesting and well-researched view into medieval folk magic and possible pagan survivals in evidence before the beginning of the witch persecutions.

Read Part One, Part Two, and Part Three

.

The late 16th and early 17th century was an era of radical social, economic, and religious change. As women had much to lose, they had reason to rebel. And they remained a threat to the new social order. Art of this period often depicted women as insubordinate and wanton: beating their husbands, swilling wine, and lustfully dragging men to bed (Merchant 133). Reformer John Knox was of the opinion that if a woman was presumptuous enough to rise above a man, she must be "repressed and bridled" (Ibid 145). This was one of the most bitterly misogynistic eras ever known.

Political and religious leaders seemed terrified by their fear that witches had organized themselves into a secret female society, as described in Kramer and Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum and King James's Daemonologie, among other works.

During witch trials, the witchfinders obsessively tried to force the accused to describe what went on at the alleged sabbat and to name the other women she had seen there. Georg Pictorious, a physician and scholar at the University of Freiburg in Germany, believed that witch persecutions were the only way humanity might be saved from these evil women. He maintained that if all the witches "are not burned, the number of these furies swells up in such an immense sea that no one could live safe from their spells and charms" (Midelfort 59).

In the 1970s and 1980s, some feminist historians such as Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English drew on Margaret Murray's study from the 1920s, The Witch Cult of Western Europe, to try to prove that there was indeed a secret society of women who practiced magic as part of an organized pagan cult. (See Ehrenreich and English's Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers)

While these speculations are very interesting, scant evidence exists to support this theory and most of it is based on torture-induced confessions.

It is, however, safe to state that people during the period of the witch persecutions sincerely believed and feared the existence of a secret female society.

Witches were believed to be a threat to both Christianity and to the middle class as it struggled to gain social authority (Hoher 46). The anti-puritan, plebian culture of lower class women stood in the way of the new values of the emerging bourgeois society. The stereotype of an organization of women out of control of society, women who cursed their enemies and mocked Christianity with their bizarre orgies, is perhaps indicative of an actual grain of reality behind the public fears. Hoher suggests that the rapidly changing society in Early Modern times, the role of the individual in a world that seemed increasingly confusing and uncertain, led to a collective insecurity--a fear that society would regress into old feudal traditions and chaos.

This fear was taken out brutally on those who would not integrate into the new order. The continuing disorder of the rural plebian culture and the refusal to conform to the new system took shape in the paranoia of the witch craze. Women, who according to Thomas Aquinas, Kramer, Sprenger, and others, were by nature weak-willed and sensual, were feared as the chief representatives of this rebellion--the chaos of uncontrolled nature and sexuality that must be subdued. Thus, it was these disorderly, uncontrollable women who were the most feared and hated. For the new order to survive, these women must be brutally exterminated (Ibid 42).

In examining the chronology of the witch trials, we see that the first trials targeted mainly poor, elderly women. As time went on and rich people and men started being accused, the witch hunts were considered to have got out of hand and they lost popular support. By this time, however, the new capitalism and religious order had been firmly established and the persecutions were no longer necessary.

This chronology reveals clearly what interests were at stake. The earliest trials of the 1560s focused almost exclusively on poor, older women. In the early trials of Wiesensteig and Rothenburg, 95 to 100% of the accused fit this stereotype. As the witch hunts progressed and the accused were tortured to name other witches, more and more men and upper class people were implicated (Midelfort 179). In Ellwangen in 1615, "accusations and convictions of highly placed and undoubtedly honorable men must have shaken people into recognizing that something had gone wrong" (Ibid 105).

Slowly the caricature of the witch as an old peasant woman was breaking down, "leaving society with no protective stereotypes, no sure way of telling who might be, and who could not be, a witch" (Ibid 182). Witch hunting so thoroughly shook up normal bonds of social trust that the most respected members of the community were no longer immune. The trials began to draw more and more criticism. Finally in 1672, the council of Altdorf in Schwaben declared all accusations of witchcraft illegal (Ibid 82). By this time, the persecutions had accomplished their original goal--the subjugation of rebellious lower class women and firmly entrenching those who survived the witch hunts into a subordinate domestic role. By the late 17th century we have no more illustrations of threatening, insubordinate women asserting their power.

Why this emphasis on poor and elderly women and why the last half of the 16th and first half of the 17th century? This period was crucial for the development of modern capitalism, a stricter moral code, and the placement of women into a narrowly defined domestic sphere, with utter economic dependence on their father or husband. The women who would most likely resist, at least in the early years of the persecutions, would be the older peasant women who remembered and clung to the old ways of plebian agrarian culture, the domestic economy, and the social and economic power they enjoyed. Such women would not easily relinquish their economic independence, their right of subsistence, or their personal freedom. The young woman beating her husband with her distaff, the symbol of her economic independence, in the early 16th century, became the old woman accused of witchcraft fifty years on. Note that in the 16th century illustrations I have included here, the old witch is depicted not with a broomstick but with her distaff.

Post-menopausal women were unburdened by pregnancies and childbirth. This gave them more freedom, time, and energy to stir up trouble. The accused witches' descriptions of the sabbat sound like the witch hunters' perversion of the joys of plebian peasant culture--drinking, dancing, and uninhibited celebration and sexuality. The earthly pleasures of the older generation became the evil heresy of the next. Since the descriptions of the alleged sabbat were drawn by torture, we must be cautious when drawing conclusions, but it makes a certain amount of sense in this historical context.

The women who had been strong, economically independent, and pleasure-loving members of the previous generation would not throw away their old privileges easily, so they became the witches of the new generation, a threat to society that had to be violently subdued for the new order to become established.

Sources:

Hoher, Friederike, "Hexe, Maria und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichket im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol III) Kuhn/Rusen, (eds.). Padagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Merchant, Carolyn, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Midelfort, Erik, H.C., Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations Stanford, 1972.

Ruether, Rosemary, New Woman/New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation, Seabury Press, New York, 1975.

Note: This essay was my Senior Paper I wrote in 1988 while an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota. Some of the sources may seem dated, but I think most of the history still stands up.

In recent years some serious scholars have revisited Margaret Murray's contention that there was indeed a secret female society in Europe during the period of the witch persecutions. See Carlo Ginzburg's book Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath and Emma Wilby's brilliant new book The Visions of Isobel Gowdie.

This website provides an interesting and well-researched view into medieval folk magic and possible pagan survivals in evidence before the beginning of the witch persecutions.

Tuesday, 15 November 2011

The Pendle Witches and Their Magic, Part Two

Blacko Tower, a Victorian folly (ca 1890) near Malkin Tower Farm, Lancashire

The crimes of which Mother Demdike and her fellow witches were accused dated back years before the 1612 trial. The trial itself might have never happened had it not been for King James I’s obsession with the occult. Until his reign, witch persecutions had been relatively rare in England compared with Scotland and Continental Europe. But James’s book Daemonologie presented the idea of a vast conspiracy of satanic witches threatening to undermine the nation. Shakespeare wrote his play Macbeth, which presents the first depiction of a witches’ coven in English drama, in James I’s honour.

To curry favour with his monarch, Lancashire magistrate Roger Nowell of Read Hall arrested and prosecuted no fewer than twelve individuals from the Pendle region and even went to the far fetched extreme of accusing them of conspiring their very own Gunpowder Plot to blow up Lancaster Castle. Two decades before the more famous Matthew Hopkins began his witch-hunting career in East Anglia, Roger Nowell had set himself up as witchfinder general of Lancashire.

What do we actually know about Mother Demdike? At the time of her trial she appears as a widow and matriarch, living in a place called Malkin Tower with her widowed daughter Elizabeth Device, and her three grandchildren, James, Alizon, and Jennet. Her clan was very poor and supported themselves by a combination of begging and by the family business of cunning craft. The trial transcripts mention that local farmer John Nutter of Bull Hole Farm near Newchurch hired Demdike to bless his sick cattle. Interestingly John Nutter chose not to testify against her family in the trial.

Demdike’s family at Malkin Tower had a powerful rival in the form of Chattox, another widow and charmer, who lived a few miles away at West Close near Fence. Chattox allegedly bewitched to death her landlord’s son, Robert Nutter of Greenhead, for attempting to rape her daughter, Anne Redfearne. For social historians it’s interesting to see how having a fearsome reputation as a cunning woman could be the only true power a poor woman could hope to wield.

Unfortunately this could also backfire as it did with Demdike’s granddaughter, Alizon Device, who exchanged angry words with a pedlar outside Colne in March, 1612. Moments later the pedlar collapsed and suddenly went stiff and lame on one half of his body and lost the power of speech. Today we would clearly recognise this as a stroke. But the pedlar and several witnesses were convinced that Alizon had lamed her victim with witchcraft. Even she seemed to believe this herself, immediately falling to her knees and begging his forgiveness. This unfortunate event triggered the arrest of Alizon and her grandmother. Alizon wasted no time in implicating Chattox, her grandmother’s rival, and Chattox’s daughter, Anne Redfearne.

The four accused witches were interrogated by Roger Nowell, and then force-marched to Lancaster Castle, walking over fells and moorland. Both Demdike and Chattox, whose real name was Anne Whittle, were frail and elderly. It was amazing they survived the journey. In Lancaster they were handed over to the sadistic Thomas Covell, the gaoler who reputedly slashed the ears off Edward Kelly, friend of John Dee, when he was arrested on the charge of forgery. The women were chained to a ring in the floor in the bottom of the Well Tower. Although torture was officially forbidden in England, gaolers were allowed to starve and beat their prisoners at will. Being chained to a ring in the floor and kept in constant darkness would certainly feel like torture for those who had to endure it.

On Good Friday following the arrests, worried family and friends met at Malkin Tower to discuss what they would do in regard to this tragic situation. Constable John Hargreaves came to write down the names of everyone present and later Roger Nowell made further arrests, accusing these people of convening at Malkin Tower on Good Friday for a witches’ sabbat, something he would have read about in Daemonologie. The arrests didn’t stop until he had the mythical thirteen to make up the alleged coven. Twelve were kept at Lancaster and one, Jennet Preston who lived over the county line in Gisburn, Yorkshire, was sent to York. Apart from Chattox and Demdike and their immediate families, none of these newly arrested people had previous reputations as cunning folk. It seemed they were just concerned friends and neighbours who were caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Kept in such horrible conditions, Demdike died in prison before she came to trial, thus cheating the hangman. The others experienced a different fate.

The first to be arrested, Alizon was the last to be tried at Lancaster in August, 1612. Her final recorded words on the day before she was hanged for witchcraft are a moving tribute to her grandmother’s power as a healer. Roger Nowell, the prosecutor, brought John Law, the pedlar she had allegedly lamed, before her. Again Alizon begged the man’s forgiveness for her perceived crime against him. John Law, in return, said that if she had the power to lame him, she must also have the power to heal him. Alizon regrettably told him that she wasn’t able to, but if her grandmother, Old Demdike had lived, she could and would have healed him.

Mother Demdike is dead but not forgotten. By the mid-17th century, Demdike’s name became a local byword for witch, according to John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson’s Lancashire Folklore. In 1627, only fifteen years after the Pendle Witch Trial, a woman named Dorothy Shaw of Skippool, Lancashire, was accused by her neighbour of being a “witch and a Demdyke.”

History is a fluid thing that continually shapes the present. Long after her demise, Mother Demdike and her fellow Pendle Witches endure, their story and spirit woven into the living landscape, its weft and warp, like the stones and the streams that cut across the moors. Enthralled by their true history, I wrote my novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill, dedicated to their memory. Other books have been written about the Pendle Witches, but mine turns the tables, telling the story from Demdike and Alizon Device’s point of view. I longed to give these women what their world denied them—their own voice. Their voices deserve to finally be heard.

Sources:

Owen Davies, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History (Hambledon Continuum)

Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (Yale)

Malcolm Gaskill, Witchfinders: A Seventeenth Century English Tragedy (John Murray)

John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson, Lancashire Folklore (Kessinger Publishing)

King James I, Daemonologie, available online

Jonathan Lumby, The Lancashire Witch-Craze (Carnegie)

Margaret Murray, The Witch Cult in Western Europe, available online

Edgar Peel and Pat Southern, The Trials of the Lancashire Witches (Nelson)

Robert Poole, ed., The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories (Manchester University Press)

Thomas Potts, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, available online

Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic (Penguin)

John Webster, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft (Ams Pr Inc)

Emma Wilby, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits (Sussex Academic Press)

Benjamin Woolley, The Queen’s Conjuror: The Life and Magic of Dr. Dee (Flamingo)

Sunday, 23 October 2011

The Pendle Witches and Their Magic, Part 1

In 1612, in one of the most meticulously documented witch trials in English history, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest in Lancashire, Northern England were executed. In court clerk Thomas Potts’s account of the proceedings, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, published in 1613, he pays particular attention to the one alleged witch who escaped justice by dying in prison before she could come to trial. She was Elizabeth Southerns, more commonly known by her nickname, Old Demdike. According to Potts, she was the ringleader, the one who initiated all the others into witchcraft. This is how Potts describes her:

She was a very old woman, about the age of Foure-score yeares, and had been a Witch for fiftie yeares. Shee dwelt in the Forrest of Pendle, a vast place, fitte for her profession: What shee committed in her time, no man knows. . . . Shee was a generall agent for the Devill in all these partes: no man escaped her, or her Furies.

Quite impressive for an eighty-year-old lady! In England, unlike Scotland and Continental Europe, the law forbade the use of torture to extract witchcraft confessions. Thus the trial transcripts supposedly reveal Elizabeth Southerns’s voluntary confession, although her words might have been manipulated or altered by the magistrate and scribe. What’s interesting, if the trial transcripts can be believed, is that she freely confessed to being a healer and magical practitioner. Local farmers called on her to cure their children and their cattle. She described in rich detail how she first met her familiar spirit, Tibb, at the stone quarry near Newchurch in Pendle. He appeared to her at daylight gate—twilight in the local dialect—in the form of beautiful young man, his coat half black and half brown, and he promised to teach her all she needed to know about magic.

Tibb was not the “devil in disguise.” The devil, as such, appeared to be a minor figure in British witchcraft. It was the familiar spirit who took centre stage: this was the cunning person’s otherworldly spirit helper who could shapeshift between human and animal form, as Emma Wilby explains in her excellent scholarly study, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits. Mother Demdike describes Tibb appearing to her at different times in human form or in animal form. He could take the shape of a hare, a black cat, or a brown dog. It appeared that in traditional English folk magic, no cunning man or cunning woman could work magic without the aid of their spirit familiar—they needed this otherworldly ally to make things happen.

Belief in magic and the spirit world was absolutely mainstream in the 16th and 17th centuries. Not only the poor and ignorant believed in spells and witchcraft—rich and educated people believed in magic just as strongly. Dr. John Dee, conjuror to Elizabeth I, was a brilliant mathematician and cartographer and also an alchemist and ceremonial magician. In Dee’s England, more people relied on cunning folk for healing than on physicians. As Owen Davies explains in his book, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History, cunning men and women used charms to heal, foretell the future, and find the location of stolen property. What they did was technically illegal—sorcery was a hanging offence—but few were arrested for it as the demand for their services was so great. Doctors were so expensive that only the very rich could afford them and the “physick” of this era involved bleeding patients with lancets and using dangerous medicines such as mercury—your local village healer with her herbs and charms was far less likely to kill you.

In this period there were magical practitioners in every community. Those who used their magic for good were called cunning folk or charmers or blessers or wisemen and wisewomen. Those who were perceived by others as using their magic to curse and harm were called witches. But here it gets complicated. A cunning woman who performs a spell to discover the location of stolen goods would say that she is working for good. However, the person who claims to have been falsely accused of harbouring those stolen goods can turn around and accuse her of sorcery and slander. This is what happened to 16th century Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop of Edinburgh, cited by Emma Wilby in Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits. Dunlop was burned as a witch in 1576 after her “white magic” offended the wrong person. Ultimately the difference between cunning folk and witches lay in the eye of the beholder. If your neighbours turned against you and decided you were a witch, you were doomed.

Although King James I, author of the witch-hunting handbook Daemonologie, believed that witches had made a pact with the devil, there’s no actual evidence to suggest that witches or cunning folk took part in any diabolical cult. Anthropologist Margaret Murray, in her book, The Witch Cult in Western Europe, published in 1921, tried to prove that alleged witches were part of a Pagan religion that somehow survived for centuries after the Christian conversion. Most modern academics have rejected Murray’s hypothesis as unlikely. Indeed, lingering belief in an organised Pagan religion is very difficult to substantiate. So what did cunning folk like Old Demdike believe in?

Some of her family’s charms and spells were recorded in the trial transcripts and they reveal absolutely no evidence of devil worship, but instead use the ecclesiastical language of the Catholic Church, the old religion driven underground by the English Reformation. Her charm to cure a bewitched person, cited by the prosecution as evidence of diabolical sorcery, is, in fact, a moving and poetic depiction of the passion of Christ, as witnessed by the Virgin Mary. The text, in places, is very similar to the White Pater Noster, an Elizabethan prayer charm which Eamon Duffy discusses in his landmark book, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580.

It appears that Mother Demdike was a practitioner of the kind of quasi-Catholic folk magic that would have been commonplace before the Reformation. The pre-Reformation Church embraced many practises that seemed magical and mystical. People used holy water and communion bread for healing. They went on pilgrimages, left offerings at holy wells, and prayed to the saints for intercession. Some practises, such as the blessing of the wells and fields, may indeed have Pagan origins. Indeed, looking at pre-Reformation folk magic, it is very hard to untangle the strands of Catholicism from the remnants of Pagan belief, which had become so tightly interwoven.

Unfortunately Mother Demdike had the misfortune to live in a place and time when Catholicism was conflated with witchcraft. Even Reginald Scot, one of the most enlightened men of his age, believed the act of transubstantiation, the point in the Catholic mass where it is believed that the host becomes the body and blood of Christ, was an act of sorcery. In a 1645 pamphlet by Edward Fleetwood entitled A Declaration of a Strange and Wonderfull Monster, describing how a royalist woman in Lancashire supposedly gave birth to a headless baby, Lancashire is described thusly: "No part of England hath so many witches, none fuller of Papists." Keith Thomas’s social history Religion and the Decline of Magic is an excellent study on how the Reformation literally took the magic out of Christianity.

However, it would be an oversimplification to state that Mother Demdike was merely a misunderstood practitioner of Catholic folk magic. Her description of her decades-long partnership with her spirit Tibb seems to draw on something outside the boundaries of Christianity.

Although it is difficult to prove that witches and cunning folk in early modern Britain worshipped Pagan deities, the so-called fairy faith, the enduring belief in fairies and elves, is well documented. In his 1677 book The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, Lancashire author John Webster mentions a local cunning man who claimed that his familiar spirit was none other than the Queen of Elfhame herself. The Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop mentioned earlier, while being tried for witchcraft and sorcery at the Edinburgh Assizes, stated that her familiar spirit was a fairy man sent to her by the Queen of Elfhame.

Saturday, 27 August 2011

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change--Germany: 1560 - 1660

Burning witches, 1555.

PART THREE

(Read Part One and Part Two.)

Major witch hunting panics arose in the 1560s throughout Europe and were especially severe in the German Southwest. Who were the victims of this mass hysteria? Even though witches were believed to come from all social classes, the trials focused on poor, middle-aged or older women (Merchant 138). Throughout Europe, midwives and healers were particularly suspect. These "wise women" who healed with herbs were held especially suspect, as they were often older women who had astonishing empirical knowlege, which their accusers traced back to the devil (Rauer 121). Many other women were targeted, as well. Outsiders and women on the fringe of society were especially vulnerable. Fifty-five of the seventy-one accused witches executed in Rottenweil, Germany, after 1600 came from outside the community, and their execution reflected both xenophobia and "a hatred of the unusual and rootless" (Midelfort 95-96). The blatant persecution of the poor prompted one accused witch in Wiesenstieg to ask her inquisitor why rich women were never arrested (Ibid. 169). Thus, though the witch panics took different forms at different times and places, they never lost their essential character--that of a campaign of terror against lower class women in search of substinence.

The question we must ask when presented with this information is why poor women and why this period in history? To invoke such massive hunts, trials, and executions, these women must have been perceived as a major threat. Whose interests did their annihalation serve? Here, I must agree with Carolyn Merchant that the control and maintenance of the social order and women's place within it was one major underlying motivation for the witch trials (Merchant 138).

The women most likely to be accused and executed were those most visibly discontent with their socio-economic condition. They were the strident women who complained about their situations and would not conform to the increasingly restrictive sphere of femininity of 16th and 17th century Europe. Sharp-tongued mothers-in-law were accused of witchcraft by their own families. Feisty spinsters or widows who refused to remarry were frequent targets of witchcraft allegations. Midelfort cites an example of a widow accused of witchcraft being released on the condition that she live with her son-in-law and remain under his control (Midelfort 184). Another common trait found among accused witches in Southwest Germany was a melancholic dissatisfaction with marriage and conventional religion (Ibid. 92) Begging and complaining about poverty were behaviors that led very frequently to accusations (Rauer 121). In 1505, Heinrich Deichsler reports in his famous Nuernberger Chronik that Barbara, a woman from Schwabach near Nuremburg, was burned as a witch after she had borrowed money from several neighbors and failed to pay them back (Schneider 18-19). The primary personality traits of witches outlined by Kramer and Sprenger in their witch-hunting manual Malleus Maleficarum were infidelity, ambition, and lust--traits that may not have been so noteworthy a few centuries before (Malleus 47). All in all, witch persecutions appeared to focus specifically on headstrong and insubordinate women.

Once a woman was labeled a witch, almost anyone could do anything to her without fear or punishment. Legally she was damned and without rights. Even before she was arrested and taken to trial, her neighbors were allowed to take justice in their own hands. Indeed, neighbors took the lead in making witchcraft accusations--it was quite common to simply call someone one disliked a witch (Midelfort 115).

Once a witch was brought to trial, she was doomed. In Germany, torture was part of the established trial procedure and could legally last for days on end. German prison guards sometimes admitted to committing rape, extortion, and blackmail on prisoners, as well (Midelfort 107). Suspects were tortured until they confessed their participation in evil magic and sex with the devil, and named the other women they had seen at the supposed witches' sabbat. Many trial officials had lists of questions to elicit responses which would conform to established beliefs about witchcraft. Dr. Carl Ellwangen began his inquisitions by asking the accused to recite the Lord's Prayer. Then he immediately asked them who seduced them into witchcraft, how the seduction occured, why they gave in, what it was like to have sex with the devil, and so on (Ibid. 105). Torture could extract almost any confession from anyone. "When suspects proved stubborn, they were often tortured to death" (Ibid. 149). Another common trial procedure reveals the inquisitors' obsession with sexuality. Women were stripped, shaved, and pricked with bodkins all over their bodies in search of supposed witch marks, or searched for signs of intercourse with the devil. In Germany, it was not uncommon for an accused witch's property to be confiscated, with Church and secular authorities receiving their share (Ibid. 178). Because accused witches were tortured until they gave the names of others they had allegedly seen at the sabbat, the more intensely witchcraft was persecuted, and the more numerous the alleged witches became. Thus, the trials and accusations escalated (Trevor-Roper 97).

On a social level, witch persecutions could not only be used to weed out the most troublesome of the undeserving poor, but they also produced a general atmosphere of paranoia and disunity among the population. Even those who consulted accused witches for healing or other services risked becomong suspect (Larner 9). The accused witch served as an example to other women as to how they would be treated if they did as she did. This, of course, helped enforce new moral and religious codes (Ibid 102). For this reason, witch hunting can be viewed as one of the most public and effective forms of social control to evolve in Early Modern Europe (Ibid 64). Witches made convenient community scapegoats for communal misfortunes such as plagues and famines (Midelfort 121). The peasant population focused their anger and resentment at members of their own peer group rather than the ruling classes who exploited them. Thus, the witch persecutions undermined solidarity and cooperation among peasants and were instrumental in curbing rebellion. In Southwest Germany, the great witch trials began not long after the Peasant Wars.

Why were such extreme measures of social control necessary? What was taking place in society at large that caused poor and elderly women to be viewed as such an enormous threat?

The period of 1560 to 1660 was one of drastic economic, religious, and social change. This period witnessed the dissolution of the last remnants of a feudal agrarian and domestic economy in favor of a capitalist market economy (Hobsbawn 5). But for this new order to succeed, the old feudal tradition, in which peasants controlled production and were guaranteed subsistence, had to die. This transition was particularly hard on women. Formerly, in the domestic economy, the workplace was the home and women were active in cottage industries. However, the transition to working in outside the home made participation in this economy more and more difficult for women. Over this period, women were forced out of the guilds and the professions in which they could maintain economic independence. Increasingly they were forced into a narrowly domestic role. By the 16th century, the only opportunities for women to earn a living were in menial servant and labor occupations (Hoher 17). Often this sort of work was so low paid that women wandered penniless and homeless in search of better conditions (Ibid. 18).

Furthermore, by this time, even such traditionally feminine occupations such as healing and midwifery were being taken over by men. In the Renaissance, the trend among the wealthy was to have a university-educated physician at their disposal. After the advent of Paracelsus, the famous medical doctor, only men were officially allowed to practice medicine. Paracelsus himself explained that God granted the educated physician all the arts and faculties most beneficial to serve others and that the doctor must be a true man and not some ignorant old woman (Rauer 109, paraphrasing "So spricht Paracelsus"). Male medical practitioners went so far as to push women out of midwifery. Eucharius Rosslin, author of the foremost "midwife" book, Der Schwangererfrawen und Hebammen rossgarten complained that midwives' supposed incompetence, laziness, and lack of education resulted in high infant mortality. He even denounces them as murderers:

Ich meyn die Hebammen alle sampt

Die also gar kein Wissen handt.

Dazu durch yr Hynlessigkeit

Kind verderben weit und breit.

Und handt so schlechten Fleiss gethon

Dass sie mit Ampt eyn Mort begon. (Ibid 123)

Women in the Renaissance not only faced an economic crisis. Their sexual and social freedom was being severely restricted, as well. Unlike the Middle Ages, the Early Modern Period offered practically no alternative to the wife-mother role. By the 16th century, the beguinages were gone. Women hermits and vagabonds risked being accused of witchcraft. Due to the Reformation and Counter Reformation, even convents had grown smaller in number and the nuns who lived there experienced increasing restrictions on their mobility and contact to the outside world. At the same time, both Catholic and Protestant Churches were tightening moral strictures to produce a puritanism unheard of in the agrarian society of the medieval period. Church officials on both sides of the faultline of the Reformation wanted to have iron control over the moral behavior of the populace. Traditional seasonal festivals, hedonism, and sexual licentiousness all smacked of ungodliness and were no longer to be tolerated. Control over female sexuality was especially emphasized. Religious offences were now punished in secular courts and in public shaming rituals. For this was a period of great religious insecurity. The cut-throat competition between Catholics and Protestants resulted in sectarian and ideological warfare, with each side trying to terrorize the local population into submitting to their orthodoxies (Reuther 104). The witch trials' obsession with female sexuality reflects this puritanical attempt to control women's lives. Tightening religious strictures and the new economic system complemented each other--they both attempted to bring the rebellious, hedonistic peasant population under control of Church and secular authorities. The witch persecutions were symptomatic of a new totalitarianism (Rauer 123).

The ideal housewife, circa 1525, by Anton Woensam.

Sources:

Hobsbawn, E.J., "The Crisis in the Seventeenth Century," Crisis in Europe 1560-1660, Trevor Aston, ed., Routledge, London, 1983.

Hoher, Frederike, "Hexe, Maria, und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichkeit im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte, Vol. III, Kuhn/Rusen, eds, Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Duesseldorf, 1983.

Institorus, Henricus, Malleus Maleficarum, Benjamin Blom, Inc., New York, 1970.

Larner, Christine, Enemies of God, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1981.

Merchant, Carolyn, The Death of Nature: Women Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Haeprer & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Midelfort, Erik, H.C., Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations, Stanford, 1972.

Rauer, Brigitte, "Hexenwahn--Frauenverfolgung zu Beginn der Neuzeit," Frauen in der Geschichte, Vol. II, Kuhn/Rusen, eds., Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, 1982.

Schneider, Joachim, Heinrich Deichsler und die Nuernberger Chronik des 15. Jahrhunderts, Wissenliteratur im Mittelalter, Vol. 5, Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1991.

Trevor-Roper, H.R., The European Witch-Craze of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Harper & Row, New York, 1969.

Sunday, 31 October 2010

All Hallows Tide in Pendle

When Halloween comes around, the popular imagination turns to ghosts and hauntings. And to witches.

Especially in my neck of the woods. I live in Pendle Witch Country, the rugged Pennine landscape surrounding Pendle Hill, once home to twelve individuals arrested for witchcraft in 1612.

Unfortunately Halloween seems to drag out all kinds of ghoulish speculation about historical witches and cunning folk in a way that is not only historically inaccurate but disrespectful to the dead. The Pendle Witches were not ghouls, but real people who were held for months in a lightless dungeon in Lancaster Castle, chained to a ring in the stone floor, before being tried without a barrister, condemned on the testimony of a nine-year-old girl, and then hanged. The historical truth is far more chilling than any fabricated horror story.

So let this All Hallows Tide be not an excuse for macabre speculation but let us light a candle in the memory of those men and women from Pendle Forest who died unjustly:

Elizabeth Southerns, Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redfearn, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Jane Bulcock, John Bulcock, and Jennet Preston.

The artist Alanna Marohnic created this illustration for my article "Mother Demdike: Ancestor of My Heart" in the new "Grandmother Gaia" issue of SageWoman Magazine. However, the magazine felt the image was perhaps too disturbing. Alanna nonetheless wanted to share her artwork with me because she felt so moved by the Pendle Witches' story, she felt it in order for someone to witness what happened to them at the gallows. It is with her kind permission that I reprint the image here.

From my novel Daughters of the Witching Hill:

You’ll not find our graves anywhere. God-fearing folk do not bury witches on consecrated ground, or even in the unhallowed plot beyond the churchyard walls where the suicides and unchristened go. After I died in gaol, they burned my corpse, then buried my charred bones on the wild heath overlooking Lancaster Castle. Three months on, they did the same to Alizon, Liza, Jamie, and the rest of them hanged upon that dazzling August day. No crosses mark our resting place, just heather and nesting lapwing. Only our names lingered on and the lies they told about us.

Away in Pendle Forest, Nowell ordered his men to bring down Malkin Tower stone by stone till only the foundation remained. Yet he could never banish me and mine from these parts. This is our home. Ours. We will endure, woven into the land itself, its weft and warp, like the very stones and the streams that cut across the moors.

What is yonder that casts a light so far-shining?

My own dear children hanging from the gallows tree.

Hanging sore by twisted neck,

How they gasp and how they thrash.

Stay shut, hell door.

Let my children arise and come home to me.

Neither stick nor stake has the power to keep thee.

Open the gate wide. Step through the gate. Come, my children. Come home.

May justice be served. May ancestral memory be served. May we dream true and have a blessed All Hallows.

Especially in my neck of the woods. I live in Pendle Witch Country, the rugged Pennine landscape surrounding Pendle Hill, once home to twelve individuals arrested for witchcraft in 1612.

Unfortunately Halloween seems to drag out all kinds of ghoulish speculation about historical witches and cunning folk in a way that is not only historically inaccurate but disrespectful to the dead. The Pendle Witches were not ghouls, but real people who were held for months in a lightless dungeon in Lancaster Castle, chained to a ring in the stone floor, before being tried without a barrister, condemned on the testimony of a nine-year-old girl, and then hanged. The historical truth is far more chilling than any fabricated horror story.

So let this All Hallows Tide be not an excuse for macabre speculation but let us light a candle in the memory of those men and women from Pendle Forest who died unjustly:

Elizabeth Southerns, Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redfearn, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Jane Bulcock, John Bulcock, and Jennet Preston.

The artist Alanna Marohnic created this illustration for my article "Mother Demdike: Ancestor of My Heart" in the new "Grandmother Gaia" issue of SageWoman Magazine. However, the magazine felt the image was perhaps too disturbing. Alanna nonetheless wanted to share her artwork with me because she felt so moved by the Pendle Witches' story, she felt it in order for someone to witness what happened to them at the gallows. It is with her kind permission that I reprint the image here.

From my novel Daughters of the Witching Hill:

You’ll not find our graves anywhere. God-fearing folk do not bury witches on consecrated ground, or even in the unhallowed plot beyond the churchyard walls where the suicides and unchristened go. After I died in gaol, they burned my corpse, then buried my charred bones on the wild heath overlooking Lancaster Castle. Three months on, they did the same to Alizon, Liza, Jamie, and the rest of them hanged upon that dazzling August day. No crosses mark our resting place, just heather and nesting lapwing. Only our names lingered on and the lies they told about us.

Away in Pendle Forest, Nowell ordered his men to bring down Malkin Tower stone by stone till only the foundation remained. Yet he could never banish me and mine from these parts. This is our home. Ours. We will endure, woven into the land itself, its weft and warp, like the very stones and the streams that cut across the moors.

What is yonder that casts a light so far-shining?

My own dear children hanging from the gallows tree.

Hanging sore by twisted neck,

How they gasp and how they thrash.

Stay shut, hell door.

Let my children arise and come home to me.

Neither stick nor stake has the power to keep thee.

Open the gate wide. Step through the gate. Come, my children. Come home.

May justice be served. May ancestral memory be served. May we dream true and have a blessed All Hallows.

Labels:

all hallows,

cunning folk,

pendle witches,

witchcraft

Tuesday, 26 October 2010

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change--Germany: 1560 - 1660

"The Evil Wife" by Israhel van Meckenem, 1440/1445-1503

A woman, encouraged by a demon, beats her husband with her distaff.

PART TWO

By the latter half of the 15th century, the feudal agrarian economy was beginning to crumble, while the capitalist market economy was growing more and more powerful, as did economic competition between men and women. Men active in the market economy tried to further their interests by simultaneously excluding women from many professions and trying to marginalize the domestic economy by claiming that home-produced goods were inferior to shop-produced goods. The guilds also began excluding women. Feeling their livelihood threatened by the competition with wealthy burghers, who set up their own industries and arranged for peasants to manufacture goods for them, male guild members struggled to initiate restrictions for women in the guilds. In 1494 in Cologne, for example, women were driven out of the harness-making guild for the first time. (Rauer 108).

In addition, traditionally "female" professions such as medicine were being taken over by men; male doctors had grown popular among the wealthy classes and were now also making inroads on medical care for the lower classes, and even encroaching on the very traditionally feminine occupation of midwifery (Ehrenreich and English 15-16--please note that the scholarship of this particular text has been called into question). Now we see the beginning of the sexual division of labor: women were beginning to be pushed into the ever-shrinking domestic economy, while men attempted to make the market economy their exclusive domain. This trend not only effected women on a purely economic level, but it also had a profound effect on women's social and sexual status. "The contraction and redefinition of women's productive and domestic roles was consistent with changes in the ideology of sexuality" (Merchant 150).

The Renaissance also ushered in a new ideal of bourgeois womanhood. The domestic sphere of the housewife and mother was idealized by Protestant intellectuals such as Martin Luther. "Gott hat Mann und Frau geschaffen, das Weib zum Mehren mit Kinder tragen; den Mann zum Naehren und Wehren," the Father of the Reformation wrote, advocating strict gender roles. "Im weltlichen politischen Regiment und Handeln antugen sie [Frauen] nichts, dazu sind Maenner geschaffen und geordnet von Gott, nicht die Weiber" (Rauer 112-113). (God created man and woman so that the woman would bear children and that the man would provide and defend. In worldly politics and trade, women should have no part--God created and ordained men for this, not women.) It must, however, be pointed out that Luther's own wife, the ex-nun Katharina von Bora was a very strong woman, beloved by her husband, who addressed her as "Herrin," or "my boss." She took charge of their household finances, farmed, raised and slaughtered livestock, and brewed vast quantities of beer to support Luther and his theology students and keep their household fed. She was the sole woman to take part in Luther's otherwise exclusively male "table talk" discussions.

Despite the positive recognition of woman as wife and mother that took place in the early Reformation, the misogynist ideology of the Catholic Church, such as Thomas Aquinas's contention that women are by nature morally weaker than men, remained in both Catholic and Protestant Churches. Also, Renaissance humanism pushed upper class women into the narrow role of being well-educated but submissive helpmates to their scholarly husbands. In 1499, Konrad Reutinger extolled his wife as the perfect Renaissance woman:

habe ich als Gattin ein Maedchen heimgefuehrt . . . schamhaft, bescheiden, schoen, etwas erfahren in den lateinischen Wissenschaften, die nie von ihren Hausgenossen streit- order schmaehsuechtig gesehen worden ist . . . . Daher weiss ich dem besten und groessten Gott jetzt und in Zukunft Dank, der meinem Studium eine Gefaehrtin und Anhaengerin gegeben hat, die mir aufs innigste vertraut ist. (Ibid 133)

(I've taken a girl home to be my wife [who is] modest, docile, beautiful, with some knowledge of Latin that those in her household have never come to view as overly ambitious or aggressive . . . . For this I thank the best and greatest God now and always, that he has given me for my studies a companion and follower in whom I trust absolutely.)

The Renaissance also saw the birth of a brand new bourgeois motherhood ideal. In the Middle Ages, mothers were expected to take care of their young children, but the mother-child bond was not as glorified to an almost sacred institution and be-all and end-all of a woman's existence as it would become in later centuries. Also, childhood, as we now view it, did not exist then; children were treated as small adults. Children of the lower classes who survived infant hunger and childhood diseases were sent away from their parents as soon as they were old enough to find work as servants in the wealthier estates (Hoher 20).

In the second half of the 15th century, the Catholic Church was losing its authority, under threat by serious challenges and dissent that would soon take the shape of the Reformation. During this divisive time, the Catholic Church expressed a new kind of religious aggression in enforcing morality and a new fascination with the devil. The hedonism that had reigned in medieval plebeian culture was no longer to be benignly overlooked. Wifely obedience in marriage began to be emphasized more and more. During this period, a new genre of literature originated: the Devil Book, which concentrated on explaining how certain activities, such as dancing and drinking, were sinful. The general effect of these publications was to imply that the devil was everywhere (Midelfort 69). The Catholic Church's attitude towards witchcraft also changed quite significantly--the ancient code saying it was sinful to believe in witches was reversed; now Church officials declared it sinful not to believe in them. They argued that a new sect had developed, which even the Fathers of the Church had been unable to foresee (Chamberlin 137). In 1484, Pope Innocent and two German Dominican friars, Kramer and Sprenger, issued a bull against witchcraft in response to rumors of widespread witch activity in Germany. This bull granted the use of inquisitorial techniques in witch hunting. Although the late 15th century was noted for religious intolerance, it was also characterized by a "new carelessness in law" (Ibid 69). The use of torture was revived with the re-establishment of Roman Law. This resulted in a considerable escalation in witch persecutions: "Torture allowed accusations to proliferate to epidemic proportions, because once a witch confessed under torture, she would be tortured again to divulge the names of her neighbors seen at the Sabbat" (Ruether 102). In 1486, Kramer and Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum was published. This highly misogynistic witch-hunting manual established the belief that women are by nature more prone to witchcraft than men: "Femina comes from Fe [faith] and Minus, since she is ever weaker to hold the faith . . . . Therefore, a wicked woman is by her nature quicker to waver in her faith, and consequently quicker to abjure the faith, which is the root of witchcraft" (Malleus 44). The authors of the book were also obsessed with the idea that the unquenchable carnal lust of women drove them to the devil: "All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which in women is insatiable . . . . Wherefore for the sake of fulfilling their lusts they consort with devils . . . it is sufficiently clear that it is no matter for wonder that there are more women than men infected with the heresy of witchcraft (Ibid 43).

As we have seen, women were beginning to be perceived as a threat to the new economic and religious developments. One cannot imagine that they were at all cooperative with the new infringements on the relative economic and sexual freedom they had enjoyed in the past. They would not submit easily to these changes--they would resist--and their resistance would make them a threat to the interests of the new order. In the arts and media of this period, women were constantly portrayed as domineering, threatening, lustful, violent, and powerful: a force that must be quelled. Village festivals of this period often had floats featuring wives beating their husbands, hurling refuse and rocks at them, and verbally abusing them. Numerous art works of this era, especially the works of Hans Baldung Grien and Albrecht Duerer, depicted the supposed disorder wrought by lusty women. Popular illustrations portrayed women beating their husbands with distaffs. Spinning was one of the occupations with which a woman could still make a decent living. The distaff symbolized her earning power and economic independence from her husband. These male artists interpreted woman's breadwinning power as something threatening, something she abused: her pride of being able to earn undermined her husband's authority. These women were not conforming to the new mold of wifely obedience that Church officials were stressing more and more. Thus, not only were women a threat to their husband's authority, they were also a threat to society in general.

One 1521 engraving by Urs Graf (unfortunately I could not find a jpeg of it to post here) depicts two young women savagely beating a monk who has probably molested them. In the Renaissance, women were portrayed as capable of violence, revenge, and self-defense. Urs Graf's women respect neither male nor religious authority; they assume the right to punish any man who tries to molest them. Hans Baldung Grien's engraving, "Aristotle and Phyllis," below, shows the legendary Phyllis literally making an ass of Aristotle. In all these pictures, women are portrayed as violent, crafty, and insubordinate. Their male victims are portrayed as pathetic, weak-willed fools for allowing themselves to be dominated by women. The message that I read into these art works is that women are trying to hold the upper hand. They will not allow themselves to be forced into the new "proper" feminine sphere. In order for women to be put in their place, men must assert their dominance. Thus, these male artists perceive women as a powerful, chaotic force that needed to be violently subdued. This violence against women would not be long in coming.

"Hercules among the maids of Queen Omphale" by Lucus Cranach the Elder: these women are emasculating the mighty Hercules by dressing him in a women's coif and pressing a distaff into his hand.

"Aristotle and Phyllis" by Hans Baldung Grien, 1513.

Aristotle who proclaimed that the male is superior to the female is shown subjected to Phyllis who literally makes an ass of him.

Labels:

art,

reformation,

renaissance,

witchcraft,

women's history

Monday, 25 October 2010

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change

I recently revisited my Senior Paper, written in 1988 at the University of Minnesota. Although some of my sources are *very* dated, most of the actual historical information seems to have stood up to the test of time and, though my focus in this paper was Germany, much of this material seems prescient for what I would later write in DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL.

Especially important in my research was the realization that women in the Middle Ages actually had more economic power and independence than they did in the Renaissance and Early Modern Period. I highly recommend Joan Kelly's iconic essay, "Did Women Have a Renaissance?", reprinted in Women, History & Theory: the Essays of Joan Kelly, University of Chicago Press, 1984.

So as an All Hallows offering, I thought I would repost my paper here, in digestible chapters. Keep in mind that I was a college senior when I wrote it, not a PhD candidate, and that I majored in German, so some of my sources are German language. Please note that in the twenty years after I wrote this papar, a lot more scholarship has been done on historical witchcraft studies, and if you are interested in reading more, please refer to the more recent books. I'll try to post a more updated reading list later.

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change: Germany: 1560 - 1660

Part One

The 16th and 17th centuries were one of the bleakest periods for European women. From roughly 1560 to 1660, the witch hysteria claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people, around 75% of whom were women, many of them older women of the lower classes (Ruether 111). One of the worst areas of persecution at this time was Southwest Germany. The question I shall try to answer in this essay is why the witch persecutions often seemed to focus on poor, elderly women. Were these women viewed as a threat to the social order to be violently subdued? What is the historical context for this? How do the persecutions relate to the rise of capitalism, the decline of the domestic economy, the male takeover of tradtionally female professions, the tightening moral and religious strictures, and the peasant rebellions? I will begin to try to answer these questions by tracing the development of the witch burnings over history and the status of women in these different historical periods: from the Middle Ages, when there were very few witch persecutions and women enjoyed relative economic and sexual freedom; to the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, when men and women began to compete in the market economy and women were beginning to be perceived as a threat, and the number of witch persecutions significantly increased; to the last half of the sixteenth and the first half of the seventeenth century, when the mass persecutions took place and women were forced into a far more restricted sphere, ecnomonically and morally, than they had experienced during the medieval period.

Very little witch persecution took place in the medieval period. Although, by the early Middle Ages, most of Europe had been at least nominally Christianized, many old pagan folk ways survived. Such tradtional seasonal festivities such as Walpurgis (May Eve), Fastnacht (the wild festivities that preceded the solemn fast of Lent), harvest homes, and the like often featured much feasting, drinking, and sexual licentiousness. Church officials did not necessarily condone these activities, but the Church, at this point in history, was content to erect a superstructure of Christianity over this rural plebian culture (Ibid 93). To a great extent, the Church looked the other way in cases of lapses in sexual morality, and men and women often did as they pleased. Thus, the customs and behaviors which would later be connected with witchcraft were tolerated and often ignored by the early medieval Church (Ibid 99).

During the Middle Ages, beliefs about what constituted magic and witchcraft slowly evolved. During the early medieval period, the Church viewed witchcraft and magic merely as pagan superstition. In the 8th century, for example, Boniface, the English apostle of Germany, declared that believing in witches was unchristian. In the same century, Emperor Charlesmagne denounced witch burnings as foul remnants of paganism and initiated the death penalty in newly converted Saxony for anyone who committed this sinful act (Trevor-Roper 92). Having firmly established witch persecutions as pagan superstition, the Church maintained a healthy skepticism in regard to the idea of witchcraft (Midelfort 14). In fact, up until the late 15th century, the Church declared it a sin to even believe in witches (Chamberlin 137). Thus, the medieval period until this point was far more "enlightened" in regard to the subject of witchcraft than the next few generations would be. As we shall see, the witch craze was a phenomenon of the Renaissance, Reformation, and early modern period.

The econominc structure of the medieval period until about 1450 was based on the feudal agrarian system, peasant control of production, and a dominant domestic economy. The peasants worked the lord's land and this guaranteed them their livelihood: from the harvest, they took what they needed for survival, while the lord took the surplus. Feudalism necessitated cooperation and interdependence on the part of peasants. For example, the introduction of the heavy plow during Carolingian times made it necessary for the serfs to work together to get a plow and a team of horses or oxen for it. They also decided communally what to plant, where they would plant, which fields to leave fallow, how crops should be rotated, and how the harvest should be divided. Although the landlord benefitted the most from this system, the peasants made the major decisions and controlled production. This subsistence ecnonomy was a domestic economy: almost all the goods necessary for survival were produced by peasant family units in the household (Ketsch 83).

The domestic agrarian economy and culture allowed women relative economic freedom. Work among the lower classes did not have any rigid gender division at the time. Male and female peasants worked alongside each other in the fields. Male and female servants of the same class often did identical work. The only female-specific work was housework, child-rearing, midwifery, and prostitution. In addition, herbal medicine and the crafts of brewing, spinning, and weaving were thought to be more "female" than "male" professions. Among the lower classes, however there was no specifically "male" work. Rigidly defined gender spheres existed only among the feudal nobility: women were responsible for reproduction and household management, while men took over martial responsibilities (Hoher 14).

No rigid gender division was evident in the market economy at this time, however. Men and women participated on a relatively equal basis in the flourishing craft guilds in the imperial cities. In the 13th through 15th centuries, women were admitted to all guilds. Although, in the early Middle Ages, there had been restrictions regarding independent female masters--that is women masters not married or related to male masters--this situation improved in the 13th century. Women began founding their own guilds and taking part on a more equal basis in the mixed guilds (Hoher 15). A document from a yarn making guild in Cologne in the last 14th century, for example, gives detailed regulations specifically regarding female apprentices and female masters: "Welches Maedchen das Garnhandwerk in Koeln lernen will, das soll vier Jahre dienen and nicht weniger . . . . Und sie soll in den vier Jahren nicht mehr als zwei Frauen dienen." (If a girl wants to learn the yarn making craft in Cologne, she must apprentice at least four years . . . . and in these four years, she should serve no more than two women.) This document also outlines the special provisions made for husbands of deceased female masters. Another guild document gives evidence for both male and female masters working in a bath house: "Kein Meister and keine Meisterin soll eines anderen Badegaeste zu sich bitten, bei einer Strafe von halben Pfund." (Rauer 104). (No male master or female master should solicit someone else's bath guest client, on pain of a fine of half a pound.) Women were also quite acrive in selling and trading, especially in materials commonly used in both medicine and folk magic. (Hoher 16).

From the 12th to the mid 15th century, Europe was underpopulated and the workforce needed women. At this time, there was little economic competition between the sexes and the split between the domestic and the market economy had not yet been fully established (Ketsch 117). So, as we have seen, women were relatively economically independent during this period.

There were also viable alternatives to the domestic sphere of marriage and motherhood during the Middle Ages. Convents attracted noblewomen who wished to free themselves from a life of child-rearing and to devote themselves to religion and learning. Beguinages--urban and secular all female communes--motivated women of the lower classes to leave the country for the city. Some women even became vagabond musicians and mercenary soldiers. There were also a few female hermits: single women who lived on the outskirts of towns and forests, and often practiced herbal medicine. These solitary women would later become victims of the witch hysteria in the Renaissance (Boulding 210-211).

The feudal agrarian system was not to last forever. The landlords' tendency to extract from unfree peasants any handy income above subsistence meant that these peansant were unable to give back what they took from the land. Thus, a combination of bad farming techniques leading to soil depletion, steady population growth, and the overtaxation of peasants by land owners all contributed to the gradual breakdown of the feudal agrarian economy and ecosystem (Marchant 47). As the feudal agrarian and domestic economy wanted, the capitalist market economy grew stronger. This had a profound effect on the socio-economic status of women.

During the years 1450 to 1550, very dramatic economic, social, and religious changes took place that would threaten the status and freedom that medieval women had enjoyed. Up until 1450, both sexes were needed in the economy, but afterwards, competition began to take place between the sexes in the market economy. It is during this period that the sexual division of labor, and the separation between the market and the domestic economy began to develop. As men struggled to gain supremacy in the market economy and to push women, their competitors, out of the guilds and into the domestic economy, which was becoming more and more marginalized, women resisted. Women were beginning to be viewed by men as a threat to the order of society. At the same time, a tightening in the moral and religious strictures in both the Catholic and the newly developing Protestant Churches began. The sexual licentiousness, dancing, and drinking that had been commonplace in the medieval period was increasingly frowned upon. Religious authorities grew more obsessed with morality, and the concepts of the devil and witchcraft than they had been before. During this period, the number of witch persecutions rose significantly. The events that took place between 1450 and 1550, thus, were decisive in laying down the foundation for the later witch crazes of 1560 to 1660.

Boulding, Elise. "Familial Constraints on Women's Working Roles," Women and the Politics of Culture, Zak & Moots, eds., Longman Inc., New York, 1983.

Chamberlin, E.R., Everyday Life in Renaissance Times, Pedigree, London, 1965.

Hoher, Friederike. "Hexe, Maria und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichkeit im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol. III), Kuhn & Rusen, eds., Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Ketsch, Peter. Frauen im Mittelalter (Vol. I) Kuhn (ed.), Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Midelfort, Erik, H. C. Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations, Stanford, 1972.